Pictures That Are Worth a Thousand Data Points

Bloomberg View , January 28, 2016

From recording police shootings and political protests to capturing street style and celebrity selfies, ubiquitous smart-phone cameras have become a new type of media, changing how the public sees the world.

The same tools are now systematically collecting new kinds of economically valuable data -- peering into hard-to-reach places, identifying emerging trends and providing a check on official numbers. Particularly useful in developing countries, this grassroots data collection may, like the phones themselves, allow formerly lagging countries to leapfrog 20th-century approaches and establish flexible, nuanced and decentralized ways of answering economic questions.

Founded in 2012, the San Francisco-based startup Premise began by looking for a way to supplement official price indices with a quick-turnaround measure of inflation and relative currency values. It needed “a scalable, cost-effective way to collect a lot of price data,” chief executive David Soloff said in an interview. The answer was an Android app and more than 30,000 smart-phone-wielding contractors in 32 countries.

The contractors, who are paid by the usable photo and average about $100 a month, take pictures aimed at answering specific economic questions: How do the prices in government-run stores compare to those in private shops? Which brands of cigarette packages in which locations carry the required tax stamp? How many houses are hooked into power lines? What’s happening to food prices? Whatever the question, the data needed to answer it must be something a camera can capture.

To check prices, for instance, contractors get a list of stores, including supermarkets, open-air farmers markets, and small corner shops. The app displays a list of which goods to photograph and record prices for. The contractors upload their photos to the company’s servers, along with GPS data and a little text if needed. Premise tests for accuracy using a combination of algorithms, computer vision, and manual spot checks. It sometimes sends another contractor back to the same place for verification.

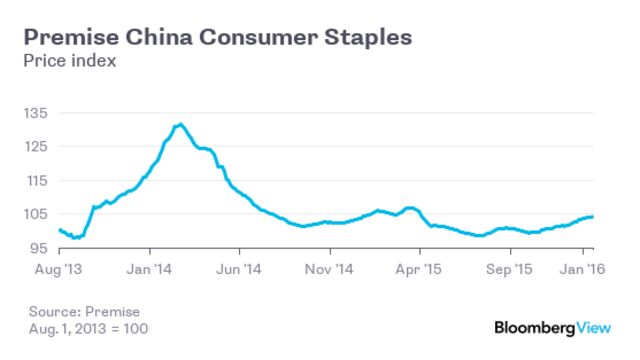

The result is a collection of price indices updated much more frequently and with less time lag -- although also fewer indicative items -- than monthly government statistics. For Bloomberg terminal subscribers, Premise tracks food and beverage prices in the U.S., China, India, Brazil and Argentina, using indices mirroring government statistics. It gets new information daily; Bloomberg publishes new data twice a week. Premise tracks a similar index in Nigeria for Standard Chartered bank, which has made the aggregate data public. (Premise clients can drill down to see differences across products, types of retailers, or regions.) While more volatile than official statistics, the figures generally anticipate them, serving as an early-warning system for economic trends.

As an example, Soloff points to what the company saw last summer in China: “Deflationary trends, all up and down the coast, specifically in the southeast -- well in advance of markets going south there, two or three months in advance. If you go back over our data, it's amazing. You see things plunging. We were like, what is going on?” Merchants were desperately slashing prices because skittish consumers had suddenly stopped buying. “People were losing money in the stock market or they were feeling insecure; they’d lost their jobs,” says Soloff. “It's not something that gets reported, but here we were.” (He said the Chinese government severely limits what Premise can collect to “a narrow band of consumer prices” and that the company observes local laws wherever it operates, lest it put contractors in danger.)

Premise has government clients, and it carefully positions its work as a complement to official statistics, as well as to the academic Billion Prices Project, which scrapes massive amounts of price data from online sources but can’t say what cooking oil sells for in a corner shop. Make no mistake, however: Its methods also provide valuable competition to the official data. The point, after all, is to find out what’s actually happening, not what government reports will say in a few weeks.

Hearing Soloff talk, I was reminded of a story my husband heard from the teaching assistant in his undergraduate macroeconomics course. Before graduate school, the young man had worked as a banker in Latin America, where he used to field calls from his country’s statistics bureau. The bureau would ask for information on banking activity, he’d pluck some ballpark numbers out of his head, "and then we would talk about soccer," he said. Even the ultra-conscientious U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics can benefit from seeing what alternative methods turn up.

Besides, Premise’s grassroots contractors can answer more granular questions than the aggregates statistics bureaus emphasize. They can compare prices from different store types, from different neighborhoods or from different parts of the same country. In Venezuela, Premise tracked how long grocery lines were, whether goods were on the shelves, and how commonly thumbprint scanners, used to ration goods, were in place. In Argentina, it compared the fixed prices in government stores to the flexible prices in the markets typically owned by local Chinese. “We found that on average the same product is 60 to 70 percent more expensive in the local market,” said Soloff. “What you have is a proxy for what the exchange rate really is when you look at those local markets.”

The same contractors who track prices can also look at other questions. Take power lines. A commercial client wanted to know the most cost-effective way to get electricity to more homes in a fast-growing East African city. Should it build off-grid capacity or subsidize the national power company to hook up houses? To answer the question, the company needed to know how many homes were electrified and how they got their power. (The national utility didn’t know.)

Using maps compiled from satellite imagery, Premise contractors photographed houses, showing which had an electric drop line. Their pictures also revealed each house’s size and construction material, indicating the residents’ financial status. Within a few weeks, Premise analyzed 60,000 homes, discovering those that were all-brick with metal roofs -- a sign of relative prosperity -- but had no power. Revisits found that in most cases the residents had generators; a few had hacked the grid. But some were going entirely without power even though they could presumably afford the electric charges. They were the ones the client particularly wanted to reach. When Premise contractors interviewed them, it turned out that the barrier was the power company’s hookup fee. The client decided to subsidize that fee for new customers, thereby bringing more people (including those with generators) onto the grid.

Premise’s big advantage is that its contractors are already on the scene. They live in these neighborhoods and shop at these markets. They know what they’re looking at. The company recruits through online advertising, especially on Facebook, and it has found that nothing beats an appeal to local pride: “If you show them a national flag and you say, ‘Tell me about where you live,’ the response rates are off the charts,’” said Soloff.

Premise reverses the usual do-gooder assumption about the Internet’s benefits for people in developing countries -- that it supplies precious information from abroad. (People in Pakistan can take online courses from MIT!) Instead, it turns those ubiquitous phones into a way of bypassing distant bureaucrats to get systematic information, collected by people who understand the local territory, out of the shadows and into the world economy.