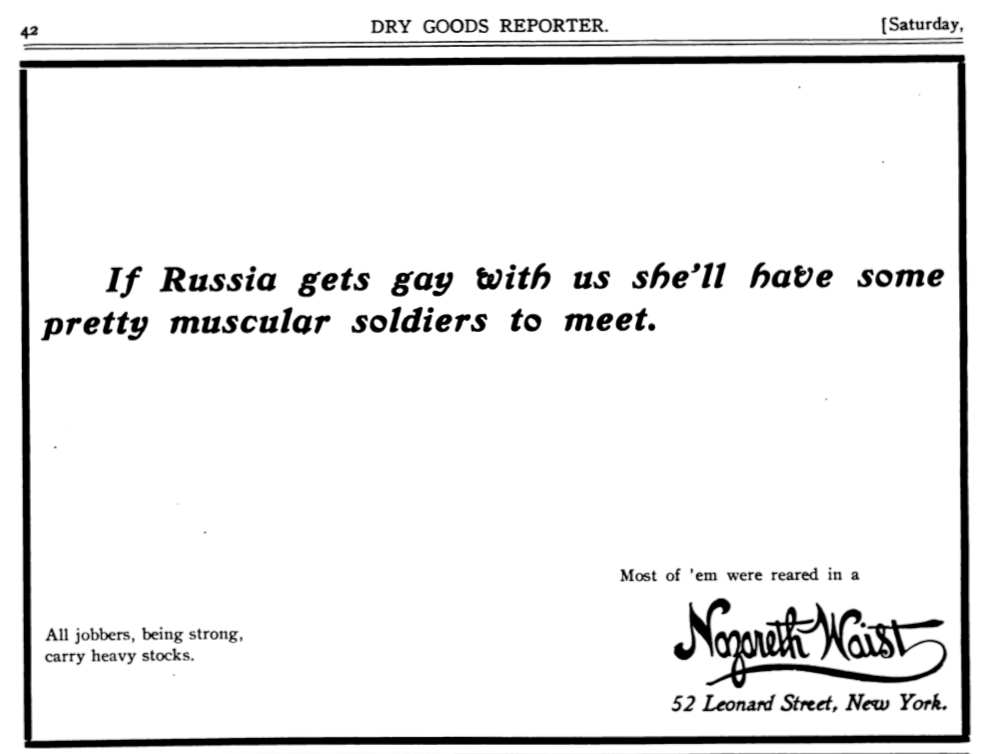

What Does This Mean? “If Russia Gets Gay With Us She’ll Have Some Pretty Muscular Soldiers to Meet”

Slate , May 29, 2014

In the era of Vladimir Putin’s territorial aggression and official homophobia, this 1903 trade magazine ad takes on resonances its copywriter never intended.

Yet even when we recognize that the copy has nothing to do with sexual orientation, its meaning remains puzzling. Why would anyone think that Russia wanted to get lighthearted and happy with us, and why would we answer with soldiers? Why would something called the Nazareth Waist Co. pick a rhetorical fight with Russia? And what about the ad’s references to muscles, strength, and “heavy stocks”? What exactly is it selling?

Deciphering the meaning of the ad, which appeared in the July 18, 1903 Dry Goods Reporter, demonstrates just how distant and mysterious even comparatively recent social history can be--this is an artifact from industrial, urban America, after all--but also how accessible today’s online riches have made that history. Answers that would have once required long hours in a well-stocked research library can now be found with a few keystrokes.

The relevant meaning of “get gay with,” a Google Books search suggests, is to provoke, threaten, harass, insult, or--to use a colloquialism equally likely to become incomprehensible with time--diss. Take this ominous sentence from the May 1913 issue of Business Philosopher magazine: “Germany, Austria, and Italy have formed a combination, and said, ‘We will help each other. If Russia, France, or England gets gay with you, just let us know, and we will help you show them where they get off.’”

In the 1903 ad, the bellicose language appears, oddly enough, in a promotion for children’s underwear. For decades, the Nazareth Waist Company advertised its wares as stretchy enough to allow vigorous exercise. “We needn’t ask if you would have the boys and girls sturdy and strong, with bright eyes and rosy cheeks. The Nazareth Waist allows them to grow, play and romp unhampered,” promised a 1895 Ladies Home Journal ad. In an urbanizing society increasingly anxious about physical fitness, the company declared its products good for kids’ development. Hence the promise that young men “reared in a Nazareth Waist” would make “muscular soldiers.” (“Heavy stocks,” by contrast, has nothing to do with muscles. It means “large inventories” held by financially strong wholesalers.)

The ad’s saber rattling marks a notable departure from the company’s usual promotions. Nazareth Waist’s trade ads typically emphasized the popularity of its products, their easy availability from wholesalers, or the brand’s ample consumer advertising. Yet in July 1903 tensions with Russia were running so high that the subject could plausibly make catchy copy to sell children’s underwear, at least at wholesale. What was going on?

Two sources of hostility had become entangled, as a search for newspaper stories on Russia reveals. One was Russia’s aggressive action in Manchuria, which would eventually lead to the Russo-Japanese war. In particular, the United States objected to the closing of treaty ports to foreigners, including U.S. merchant vessels.

The second was the Boko Haram story of its day: the brutal massacre of Jews in the Russian town of Kishineff (or Kishinef or, its common spelling today, Kishinev) over Easter. As stories of what had happened trickled out, including the role of local officials in abetting the pogrom, the incident became a cause célèbre, not only for Jews but for Americans in general. Newspapers ran horrifying accounts, relief drives took place, and B’nai B’rith organized a petition to the Russian czar asking for religious liberty and tolerance “in the name of civilization.” Opposing the massacre of Jews in Russia became an expression of American culture and values.

“Every humane American sentiment has been shocked by a late attack on the Jews in Russia--an attack murderous, atrocious, and in every way revolting,” former president Grover Cleveland said in a speech to a mass meeting at Carnegie Hall. “We belong to a Republic that stands for the rights of the weakest and justice to all sorts and conditions of men,” declared Henry C. Potter, New York’s Episcopal bishop, at a benefit performance of the play The Jew in Roumania. A Chinese-American theater company even held a special fundraising performance in New York.

As the Nazareth Waist ad was going to press, Theodore Roosevelt’s administration had indicated its intention to officially present the B’nai B’rith petition to the Russian government and the Russians, objecting to interference in their internal affairs, had indicated that they would refuse it. (The front page of the San Francisco Call’s July 2 edition captured the mood of the day, with the banner headline “STATE DEPARTMENT GIVES SHARP RETORT TO RUSSIAN THREAT AND RELATIONS BETWEEN THE TWO NATIONS ARE STRAINED.”) The petition had become both the object of negotiation itself and a potential obstacle to resolving issues in Manchuria.By the time the ad ran, however, the crisis in U.S. relations was largely over. Russia had promised to reopen Manchuria’s ports, the United States had acquiesced to its refusal to accept the petition, and Russian authorities were pledging to punish the massacre’s perpetrators. Nazareth Waist dropped its pugnacious stance and went back to telling the trade about the elastic virtues of its products.