Harvard Gets Its Geek On

Bloomberg View , June 18, 2015

When Harvard University announced that hedge fund manager John A. Paulson was donating $400 million to its engineering school, a swarm of critics pounced.

Nobody seemed terribly curious about what the money would pay for, or why Harvard has focused so much of its current capital campaign on engineering, raising money to hire more professors and build new facilities in the Allston section of Boston. Harvard has never been the Harvard -- or even the University of Pennsylvania -- of engineering. Why the sudden interest?

To find out, I talked with Harry Lewis, the computer science professor and outspoken former dean of Harvard College who is now interim dean of the newly renamed Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. Here’s an edited and condensed transcript of our conversation.

Question: Steve Ballmer’s earlier gift will pay for 12 additional faculty positions. What will the $400 million from John Paulson fund?

Answer: It's endowment, so none of the principal will be spent. The income can be used for anything that the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences decides to do. One thing the gift will not pay for is building our new campus. That money still has to be raised.

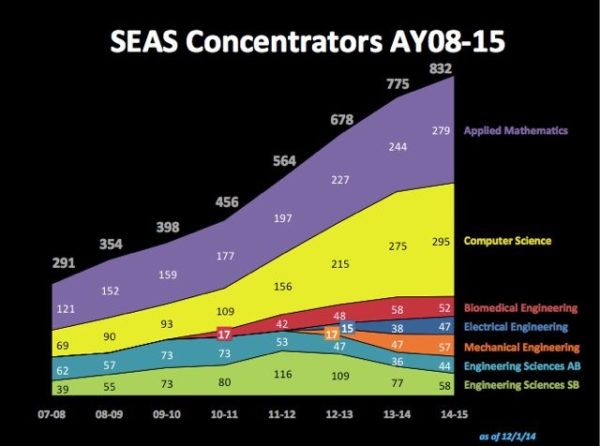

Q: Since SEAS became its own school in 2007, there’s been a striking increase in enrollment. What’s driving the demand?

A: The easy answer is we're doing a superb job of teaching our courses and we've created an infectious enthusiasm among undergraduates. And I think that's all partly true -- CS 50 [the introduction to computer science] is a cultural phenomenon at Harvard now, in a way that never used to be the case. People take CS 50 because their buddy on the lacrosse team is taking the course. Everybody knows it's a cool course, so everybody wants to take it. The same thing is happening to a lesser degree in some of the other engineering disciplines.

There’s also been a kind of cultural change at Harvard, where making things, doing useful things, is no longer -- as it certainly once was at Harvard -- considered the sort of thing gentlemen and gentlewomen didn't do. Harvard used to be a place where pure science was revered and applied science was not particularly respected. And that's very much not the case now.

Q: What time period has that change taken place over?

A: A decade or so. Ultimately, the Allston move arose from a conjunction of the university's recognition that Harvard could not be a great university in the 21st century if it didn't have a great engineering school, and students recognizing that there were lots of things they could learn by taking our courses that would help them to solve the world's problems in a way that not only had significant impact but was fun.

I also think the socioeconomic shift in the student body has had an impact. We have more students with very high financial aid needs, and we have more students who come from rural backgrounds and from first-generation immigrant backgrounds, and more students who come from families therefore where engineering is one of the natural things that you might want to get an education to do. I think that's led to some of the increase in our enrollments as well.

Q: CS 50 has been the largest class at Harvard for the past five years, with more than 800 undergraduate students last fall. Is this expansion really a story of computer science, with the other disciplines just along for the ride?

A: That wouldn't be correct. Computer science is a story unto itself, partly because of that course, partly because of the very successful computer companies that were born at Harvard, but also because computer science scales easily. It's not hard to go from teaching CS 50 to 400 students to teaching CS 50 to 800 students. They have their own laptops anyway, so we don't even pay for the computers. There are some servers -- we actually use Amazon Web Services for a lot of it -- but it's easy to get more computing resources.

In mechanical and electrical and biomedical engineering, you need actual lab benches and equipment, and this is really where we're crunched now. We've got a Eco Marathon club. They're building very high-efficiency vehicles. It's a really cool project. Guess what: You need a garage to do that. There's no garage space in our buildings. We've got them crammed into a tiny lab that's been hollowed out of a sub-basement. The physicality of these other engineering disciplines makes them harder to scale.

Q: SEAS has relatively few different majors, compared with traditional engineering schools. There’s no chemical engineering/materials science or civil engineering, for instance. Do you anticipate adding any programs?

A: We're not going to be MIT. We're not going to have a department of naval engineering. We probably won't have civil engineering, at least as traditionally understood.

I think the kinds of things that are most likely to happen at Harvard are the things where Harvard's engineering school can play off other strengths. Harvard has enormous strengths in medical research, for example. Harvard has enormous strengths in applied physics. So the areas of engineering that relate to those two other scientific fields would be natural places for things to happen at Harvard.

The chemical engineering example is interesting, because in the old days, chemical engineering meant petroleum engineering and dyes and soaps and things like that. Chemical engineering now is very much part of material science and what we might otherwise call bioengineering research. One of the things I like about SEAS is we don't have a departmental structure where you have to declare yourself: Are you really a chemical engineer? Are you really a materials scientist? We hired a new junior faculty member as a result of a robotics search. Robotics is not a traditional engineering discipline per se. Some people who work in robotics have mechanical engineering backgrounds, but some of them electrical engineering backgrounds and some of them have computer science backgrounds. When we hired this fellow, we said, What do you want to be called? And he said, I want to be called computer science. So he's a professor of engineering and computer science, because there was no departmental structure that forced us to classify him.

Q: In an interview with the Crimson, you said, “We’re at the beginning of something huge here.” What did you mean?

A: We are moving to a tiny corner of a very large undeveloped tract of land in the city of Boston, very close to developed areas of Boston, and we will have an economic impact on what happens there. My analogy is it's going to be like what happened to the Longwood area of Boston after the medical school moved there in the first years of the 20th century. In 1900 there was nothing in Longwood. Now it's the center not only of medical education but of medical research, of clinical medicine, and of the whole biopharmaceutical industry. So my prediction is, and my firm belief is, that Harvard engineering is going to have the same effect on the city of Boston in the 21st century that Harvard Medical School had on the city of Boston in the 20th century.

Q: You also talked about “getting people to buy into the idea that they’re here doing something important and that we’re in the futures business.” What did you mean? Who are you trying to convince?

A: Our students, our alumni, our faculty colleagues from outside engineering. I'm arguing here for the importance of engineering and applied science as a discipline, rather than as a tool to be used by other people to solve their problems. We've always, in computer science and other areas of applied science, fought the perception that other people come to us with neatly formulated problems and then we do a couple of equations, or write a couple of programs, and give them back the solution. That's not the way serious problems get attacked, and it's certainly not the way inventions get created.

My own background is in computer science, and I have the peculiar distinction of having had both Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg in class. They were not solving problems that anybody gave them. There was not some grand challenge out there: write a compiler for microcomputers. Just the opposite -- students were being taught that they should be working on big mainframe computers. Same thing with social networking. Social networking was a concept in sociology. It wasn't a concept in technology.

You have to have an environment where very bright students who don't always drive 100 percent between the lines can recognize things that nobody's imagined doing before and then go do them. So when I say we're in the futures business, that's really what I mean.

Q: It strikes me that a lot of this investment in engineering is driven by Harvard’s need to protect its brand position.

A: Rather than call it brand protection --

Q: I figured you wouldn’t like that word --

A: I understand the vocabulary, but the reality of it is, the most powerful governance body at Harvard, the Harvard Corporation, realized that Harvard, which got along for a very long time without having a first-rate engineering school, in the 21st century was not going to be able to remain one of the greatest universities in the world if it didn't have a first-rate engineering school. Call it brand protection if you want. I would just call it an awakening to the problems of the future, in the way that they were problems of medicine in the 20th century. In the 21st century, many of the most important problems of the world are going to be engineering problems and information science problems and computational problems. I wish Harvard had figured it out sooner, but there are advantages to taking it up now, because we can make it the way that we want to make it for the century that we're going into rather than having the inherited structures of 19th-century engineering.

Q: Some at Harvard worry that the school is losing its identity as a liberal arts institution as more students concentrate in engineering and computer science. What’s your take on that?

A: There's no reason why we have to be one or the other. We've always had among the greatest mathematics departments of the world at the same time that we've had among the greatest history and literature departments of the world, so why shouldn't we have those and also have among the greatest engineering schools of the world?

Q: I went to Princeton, so obviously I don’t disagree with that, but it does change the culture.

A: But Harvard has already changed the Harvard culture, by bringing in lots of students who don't have fancy educational backgrounds. We probably see more of these students in the engineering school, but they're all rooming together and eating together and so on, and that's been the result of the enormous investment in undergraduate financial aid that Harvard has been making for the last 15 years. That's created an enormous cultural change.

Q: What feels different about Harvard as a result of that change?

A: It's just more interesting, because you have all of these really bright, ambitious students who have a very different frame of reference than their roommates from fancier zip codes. It's great. Particularly in a residential college like ours, it just improves the amount of educational interchange that happens between students and between students and faculty.

Q: John Paulson’s $400 million gift attracted a feeding frenzy of harsh criticism. Did that surprise you?

A: Nothing surprises me. Everybody loves to hate Harvard except the people who love to love it.