How Job-Killing Technologies Liberated Women

Bloomberg Opinion , March 14, 2021

As the many mothers who’ve left their jobs to cope with pandemic remote schooling can testify, “free” household labor isn’t really free. It always entails the opportunity cost of what you could otherwise be doing.

But women’s domestic tasks get short shrift in the history of labor-saving technology because historically much of that work received no direct monetary compensation. “We are all familiar with our grandmothers’ adage, ‘A woman’s time is nothing,’” wrote an essayist in 1870, lamenting how little inventive effort was going toward easing women’s domestic burdens. Whether by unpaid housewives or poorly paid servants, the work still had to be done.

March is Women’s History Month, a good time to remember that the history of women’s work sheds light on the broader questions raised by labor-saving technologies, past and present. Viewed through the lens of women’s experiences, inventions often derided as job-killers look like “Engines of Liberation,” the title of an influential 2005 article by economists Jeremy Greenwood, Anath Seshadri and Mehmet Yorukoglu.

By making women more productive and opening new demands for their services, labor-saving technologies gave them greater control over their time, more freedom to choose their occupations and the earning power to shape their own lives — all while propelling economic changes that boosted the overall standard of living.

Consider a few examples:

The Water-Powered Grist Mill

This technology for grinding grain spread through Europe in the Middle Ages, revolutionizing how women spent their time. To digest cereal grains like wheat, humans first have to remove their husks and turn them into flour. That means many hours of pounding and grinding. As late as the 1990s, women in rural Mexico were still using these traditional methods to produce masa, the corn flour in tortillas. Food historian Rachel Laudan estimates that it takes about five hours of grinding to produce enough masa to supply a family of six with a day’s tortillas.

Grist mills opened up women’s time for other tasks, most prominently spinning. Less arduous than grinding grain, it was no less necessary or time-consuming. A Medieval woman using a spinning wheel would have spent about 110 hours spinning enough wool for a pair of trousers.

By freeing women to produce more yarn, historian Constance H. Berman argues, grist mills enabled the wool-based trade that set off the commercial revolution of the late Middle Ages, leading to new financial institutions and the rise of prosperous new centers like Antwerp, London, and Florence. “It is possible that without this change in women’s work,” she writes, “such industry would not have taken off as it did.”

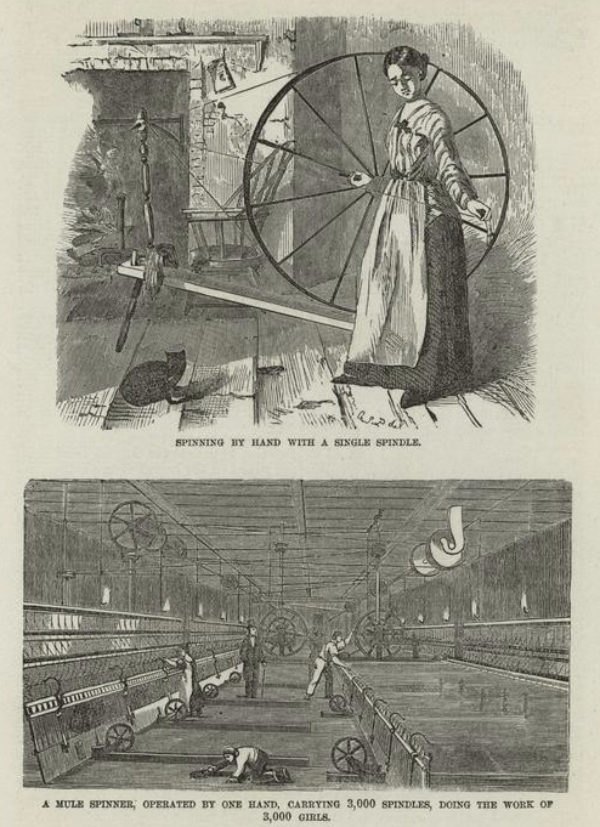

Spinning mills

Spinning remained the bottleneck in textile production. “The spinners never stand still for want of work; they always have it if they please; but weavers are sometimes idle for want of yarn,” wrote the agronomist and travel author Arthur Young, who toured northern England in 1768. Supplying a single weaver, he noted, took at least 20 spinners.

In a workforce of 4 million Britons, economic historian Craig Muldrew estimates, well over a million women were working as spinners. Their labor was the biggest expense in cloth production other than raw fiber, often totaling more than twice the cost of weaving. Yet spinners’ wages were pitiful, for the simple reason that it took so many hours to produce a useful amount of yarn. The spinning machines that set off the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s changed that calculus. Suddenly yarn that once required days to spin could be had in hours, or even minutes.

Before the Civil War, the “mill girls” of New England found new independence in the region’s textile plants. Although the work was grueling, the mills gave young women their own incomes and a chance to broaden their horizons. “There are girls here for every reason, and for no reason at all,” one wrote in an 1844 edition of the Lowell Offering, a magazine published by female mill workers. Many were drawn by the opportunity to buy their own clothes. By making “pretty gowns and collars and ribbons” affordable, the textile revolution created a powerful enticement to cash employment.

Even when wages and working conditions worsened, mill work gave women new forms of autonomy, including the role of labor leaders. The work offered women a public identity, beyond hearth and home.

Rotary presses

That mill girls could publish their own literary magazine testifies to another invention rarely noted as a liberator of women: the steam-powered rotary printing press. Invented in the 1840s, it increased printing speeds tenfold, a pace soon doubled by an invention allowing machines to print both sides of the paper simultaneously. By lowering the cost of high-volume printing, the new technology vastly expanded the market for books, magazines and newspapers — and the writers to fill them.

Fiction writers like the Brontë sisters and Louisa May Alcott, as well as many now-forgotten popular authors, could now make an independent living. With “Jane Eyre,” Charlotte Brontë earned 25 times her salary in the hated job of governess. Alcott ground out “blood and thunder tales” for magazines and wrote “Little Women” for the money.

“Newspaper girls” filled the columns of the mass-market press. Touting their own lifestyle in articles, they created a new model of “the bachelor girl,” a single professional woman distinct from the sad stereotype of the old maid. “These women are for the most part our best modern type, educated, energetic, independent, enterprising,” declared the New York Press in 1894.

Some female journalists offered womanly advice or chronicled the social whirl, while others pursued investigative reporting. In her Memphis newspaper, Ida B. Wells exposed lynching in the South. New York World reporter Nellie Bly went undercover in a mental hospital. Elizabeth L. Banks labored in sweatshops on the Lower East Side and lived on $3 a week, “telling each day in the paper just what I had to eat, and describing all my comforts and discomforts.” In London, she hired out as a maid and worked in a laundry.

The sewing machine

It was widely recognized as the exception to 19th-century inventors’ indifference to the value of women’s time. “It is the only invention that can be claimed chiefly for woman's benefit,” declared the New York Times in 1860. A sewing machine bought on time could clothe a family or set up a business.

Working with a hand needle, a good seamstress took about 14 hours to make a shirt. With a sewing machine, she could do the same job in an hour. It was an early example of “the robots are taking our jobs.” In an 1888 essay titled “Labor-Saving Machines as an Evil,” the Ohio journalist Samuel Rockwell Reed used the sewing machine as a prime example, singling it out for “enhancing the hard fate of women” by putting hand-sewers out of work. A single machine, he calculated, “deprives 25 children and five widows of bread.”

The claim was actually satirical. Human history, Reed pointed out, is a progression of such inventions. The steel needle replaced the bone needle, with which “three or four wives might be sufficiently employed in making up one man’s rude garments, whereas such facility was given to this by the invention of the steel needle that he hardly had a need of one wife.”

Instead of impoverishing widows and orphans, the sewing machine made seamstresses more productive, giving rise to a large ready-to-wear industry. Although we now remember it mostly for its sweatshops and the labor activism they sparked, it offered generations of mostly female workers, from the Lower East Side to Vietnam, the first step out of poverty.

The washing machine

Elizabeth Banks’s stint wading through soapy water points to another liberating invention: the electricity-powered washing machine. Before its arrival, laundry was such a laborious task that even poorly paid shop girls hired someone else to do it. Just reading the list of “equipment for a home laundry” in a 1900 laundry manual is exhausting.

In “Engines of Liberation,” Greenwood, Seshadri and Yorukoglu cite a study of farm wives that found that doing a 38-pound load of laundry by hand required four hours, with another four or five for ironing. Using electrical appliances, the washing took just 41 minutes and the ironing an hour and 45 minutes. The number of steps walked in the process was cut almost 90 percent. “No man worth his salt would spend a seventh of his time at a tub,” declared journalist Allan L. Benson in a 1912 Good Housekeeping article.

“Power laundry machinery is not so expensive that people in ordinary circumstances cannot afford to buy it, whereas washing by hand is so hard that no woman should do it,” Benson wrote. “It makes no difference who the woman is, whether she is a housewife or a servant, washing is too hard for her. In the winter, it invites pneumonia. At all times of the year, it is drudgery.”

Synthetic fibers

A 19th-century laundress would have envied her 1940s counterpart, but even by the mid-20th century, washing, drying and ironing still took plenty of time and attention. The invention of nylon in 1934 set off a materials revolution — the advent of synthetic fibers and plastics — and further eased the laundry burden.

Synthetic fibers fostered a fundamental fashion shift that continues to today’s pandemic yoga pants. “More than looks,” writes business historian Regina Lee Blaszczyk, “the characteristic that I call ‘high performance’ distinguished the panoply of postwar products from their early-20th-century predecessors….Curtains that could be drip dried, uniforms that never needed ironing, and sweaters that could be washed without shrinking reduced domestic burdens.” When large numbers of American women entered the workforce in the 1970s, they did so wearing easy-care polyester pantsuits.

Over the succeeding decades, synthetic fabrics got better — softer, more breathable, less likely to snag and pill, more varied in look and feel. Today’s women — and men — are free to use their time in more productive and fulfilling.

Looking back on the endless labors of our foremothers reminds us that it’s easy to create jobs by making work harder and slower. But you create wealth — and freedom — by making it faster and easier. The next time you throw a detergent pod into a load of clothes and go off to work on your laptop, consider all the could-be washerwomen now doing something else.