Making History Modern

Reason , December 2017

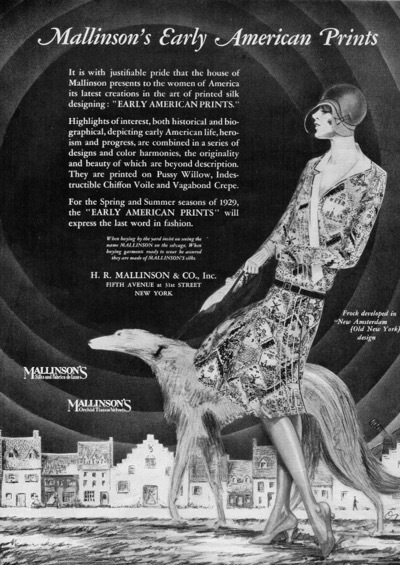

She is an icon of 1920s modernity: an independent woman with bobbed hair and a short skirt, walking with her streamlined Borzoi, the quintessential Art Deco dog. Behind her is a New York City street. But instead of skyscrapers and neon lights, it's lined with old-fashioned chimneyed houses.

This image, with its up-to-the-minute foreground character and historic background tableau, is from a series of 1929 ads promoting the new season's print fabrics from H.R. Mallinson & Co., a major silk-textile manufacturer. In a second ad, the modern woman, hand on hip, twirls her long pearl necklace in a stereotypical flapper gesture. In the background is a monument featuring the Mayflower and a hopeful-looking Pilgrim couple. A third ad shows the woman standing with her hand on a ledge, gazing thoughtfully in a pose that mirrors the bust of Abraham Lincoln looking down at her.

Mallinson sold its silks around the world, but it was a resolutely American company, boasting from the start that it produced "national silk of international fame." It carried its identity into its textile designs. Earlier themes had included state flowers, National Parks, American Indians, and "Wonder Caves of America."

The prints were promotional items, offering retailers something splashy for their windows and their newspaper ads—but the goal was to attract customers to the company's basics. "You went in and you bought a yard of an American Indian silk to make a blouse and five yards of navy blue to make a suit, and that's where they made their money," says textile historian Madelyn Shaw.

The prints ran $4.50 a yard, or $64.42 in today's dollars, a price point that explains why they tended to sell in smaller quantities. "This was not an inexpensive silk," Shaw says. "You thought about it as an investment."

Investing in fabric with pretty pictures of flowers, scenery, or Native American motifs is one thing. But why would someone want to wear "Life of Lincoln," "Mayflower Pilgrims," or "Old New York"? After all, modernity, not history, was exciting and glamorous in the late 1920s. Intoxicated by the promise of a world made new, artists and intellectuals were ready to scrap all that had come before.

But Mallinson wasn't selling to artists and intellectuals. It was selling to American women, and in that context, its historical motifs were right on trend.

Influenced by old movies, we imagine interiors from the 1920s and '30s with Art Deco furnishings. In real life, Americans who could afford nice things outfitted their homes with Georgian styles: four-poster beds, Wedgwood china, Windsor chairs, chintz fabrics, and pastel colors. This Colonial Revival look was sleeker and lighter than fussy Victorian styles, but traditional enough to seem homey.

Everyday Americans wanted to be modern. They wanted automobiles, refrigerators, and washing machines. Women wanted to bob their hair, shorten their skirts, go on dates, and maybe even vote. But they didn't want to start the world from scratch. Few were looking to give up family life, good manners, religious faith, or the Constitution. They sought continuity as well as change.

With words and images, Mallinson's prints told customers they could have it all: pride in America's heritage and the best modernity had to offer.

Abstracted and collage-like, the designs themselves were au courant. Slanting lines reaching toward the sky through fields of stars dominate "Betsy Ross-Liberty Bell." The play of stripes and stars recalls streamlining and movie-premiere searchlights, not patriotic banners. "The story of the flag [is] so cleverly treated there is a modernistic effect," pronounced a Louisiana department store ad. Overlaid with speed lines, the Liberty Bell and Philadelphia's Independence Hall stretch upward like grand modern skyscrapers. Only on close examination do tiny colonial figures appear.

"Franklin's Key to Electricity" makes the connection between past and present explicit, intertwining Ben's famous kite tail with power lines and tiny lights. The collage of images includes telephones, automobiles, and a modern couple dancing on a musical score—as well as a sailing ship, a carriage, a colonial figure reading, and, of course, Franklin himself holding his kite string with its key. Abstraction, balance, and the adept use of color keep the design from seeming overly busy.

A dress made of this print sold at auction last fall for $4,200 and is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Costume Institute collection. Its dominant motif is what looks like a sunburst—the promise of a great new day.

Mallinson described the designs as "depicting early American life, heroism and progress" (emphasis added). It wasn't selling nostalgia for the good old days. It was casting America's past as the beginning of a future-oriented story.

Modernity represented not a radical break from those early times but the fulfillment of their promise. Nor did the American past belong only to the descendants of Pilgrims or pioneers. Anyone with $4.50 a yard could claim it.