The Iconographer

In Julius Shulman's photographs, modern architecture became seductive, comfortable, and immortal

The Atlantic , November 2006

In the fall of 1919, a young Austrian architect dreamed of escape—escape from the frigid European winter, from the “psychological collapse” of a demoralized culture, from the “empty cheerless drafting” that consumed his workdays. “I wish I could get out of Europe,” he wrote in his diary, “and get to an idyllic tropical island where one does not have to fear the winter, where one does not have to slave but finds time to think, or even more important, can have a free spirit.” A travel poster in Zurich obsessed him: California Calls You, it read.

The advertising worked. In February 1925, Richard Neutra and his family settled in Los Angeles. “I found what I had hoped for,” he wrote, “a people who were more ‘mentally footloose’ than those elsewhere, who did not mind deviating opinions … [a place] where one can do almost anything that comes to mind and is good fun.”

Good fun, indeed. In the golden sunlight and quirk-tolerant culture of southern California, modernism’s glass walls and white boxes lost their sternness. Instead of a visual lecture on Machine Age precision or the evils of ornamentation, the modern architecture—above all, its home design—became the setting for a new kind of life or, as we’ve come to call it, lifestyle: comfortable and convivial, a place where outdoors and indoors, leisure and ambition, nature and artifice, mind and body can happily coexist.

To the mission architecture of the old travel posters, Neutra and other California modernists added new symbols of the good life, or at least their raw materials: the walls of glass, inviting patios, flat roofs, and sliding doors appropriate for free spirits in a kind climate. To turn those buildings into icons, however, someone had to transform steel and stone into reproducible images, emotionally resonant and frozen in time. That person was the photographer Julius Shulman, who met Neutra in 1936. One of Neutra’s apprentices was boarding with Shulman’s sister, and he took young Julius along on a visit to the nearly complete Kun House. Just for fun, Shulman, then an aimless student who’d been auditing courses at Berkeley and UCLA for seven years, shot photos of the unusual house, using his pocket camera and a tripod. When Neutra saw the snapshots, he recognized the young man’s special talent: an ability to capture the aesthetic and emotional intention of designs. For the next thirty-four years, until Neutra’s death in 1970, the two collaborated. Through his work with Neutra, Shulman met other California modernists, including Rudolf Schindler, Raphael Soriano, Charles and Ray Eames, Albert Frey, John Lautner, and Gregory Ain. The architects built the buildings, but Shulman created the evocative images through which we know them.

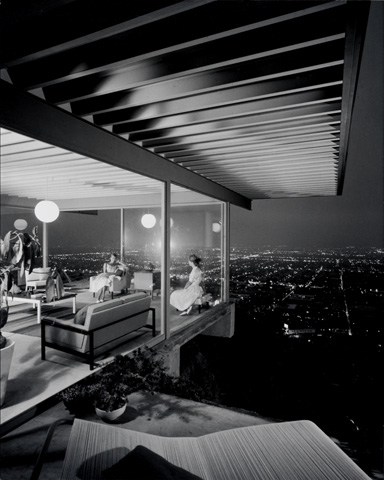

His 1947 twilight shot of Neutra’s Kaufmann House, in Palm Springs, with Mrs. Kaufmann reclining by the pool and the bright house sharply delineated against the misty desert hills, has come to represent Palm Springs, mid-century modernism, and Neutra himself. Even more resonant is Shulman’s 1960 photograph of Pierre Koenig’s Case Study House No. 22, another twilight scene. Here two young ladies converse in a glass-enclosed living room that juts out toward the sprawling city grid of tiny lights. The architecture critic Paul Goldberger called the photograph “one of those singular images that sums up an entire city at a moment in time.” Less obviously glamorous but equally inviting is the 1946 photo of Gordon Drake’s tiny, ingeniously designed home. Shooting from seated eye level across the living room, Shulman draws the viewer through the open glass door to the patio, where three young friends read and converse in an intimate space protected by the hillside immediately behind them. “He has portrayed what it’s like to live in the modern house,” Shulman pronounced in an interview, suggesting how I should describe his work.

In fact, he has portrayed something more powerful: an ideal of what it’s like to live in a modern house. Shulman’s photographs are not simply beautiful objects in themselves or re-creations of striking buildings; they are psychologically compelling images that invite viewers to project themselves into the scene. An architectural photograph can conjure three possible desires: “I want that photograph,” “I want that building,” or “I want that life.” Shulman’s best work evokes all three. At a time when the public thought of modernism as a cold, impersonal style suited only for office buildings, he made its houses look seductively human. His photos do not merely record modern architecture, California style; they sell it. “You make people want to say, ‘Gosh, I could lie down on that couch and take a nap.’ Or, ‘I’d love to sit at that table and have dinner there. Or entertain company around the fireplace,’” he recently told an audience at the National Building Museum, in Washington, D.C.

In fact, he has portrayed something more powerful: an ideal of what it’s like to live in a modern house. Shulman’s photographs are not simply beautiful objects in themselves or re-creations of striking buildings; they are psychologically compelling images that invite viewers to project themselves into the scene. An architectural photograph can conjure three possible desires: “I want that photograph,” “I want that building,” or “I want that life.” Shulman’s best work evokes all three. At a time when the public thought of modernism as a cold, impersonal style suited only for office buildings, he made its houses look seductively human. His photos do not merely record modern architecture, California style; they sell it. “You make people want to say, ‘Gosh, I could lie down on that couch and take a nap.’ Or, ‘I’d love to sit at that table and have dinner there. Or entertain company around the fireplace,’” he recently told an audience at the National Building Museum, in Washington, D.C.

Shulman was discussing an eighty-three-piece retrospective of his work, “Julius Shulman, Modernity and the Metropolis.” Organized by the Getty Research Institute, which in January 2004 bought his enormous archive, the exhibition opened first in Los Angeles on October 11, 2005, the day after the photographer’s ninety-fifth birthday. (It is at the Art Institute of Chicago through December 3.) More than a survey of a great photographer’s work, or of the architecture he documented, the exhibition is a glamorous composite portrait of the city that defined twentieth-century urban form. As modernity’s metropolis, Los Angeles looks nothing like Fritz Lang’s futuristic vision. Here are low-rise office buildings and backyard patios, car dealerships and gas stations, poolside chaises and sliding glass doors—a horizontal metropolis of private space. Here even Ayn Rand, whose Fountainhead celebrated skyscrapers as “the shapes of man’s achievement on earth,” socializes within the curving aluminum wall of her Neutra-designed patio.

Modernity, it turns out, built a metropolis with a form so unprecedented that residents and critics still refuse to consider it a real city; it’s a suburb without a core—which is to say, not a suburb at all—and, in the United States, increasingly a place where one does not have to fear the winter. The suburb is not, as Frank Lloyd Wright and others imagined, a place to escape the city; it is the city, the place where, as Neutra hazily imagined, country and city merge, where you can get “fresh air here, speakeasies and museum treasures there.” By the end of the twentieth century, more than half of all Americans were living in metropolitan areas of more than a million people—“metropolitan areas,” not city limits—of which Shulman’s southern California is by some definitions the most densely populated. Hence the traffic congestion.

Good architecture, Shulman believes, still promises a better life. He showed me his pictures of the Encino home that the architect Raquel Vert designed for herself in the mid-1990s. Shulman took the street-front photograph when the shadows from the foliage were at their thickest, to create “an effect of privacy and isolation.” Unlike its mid-century predecessors, Vert’s house is not isolated at all; it’s right up against the street, in a tract dense with houses. Her design creates privacy in part by recessing the front door behind a concrete wall. Immediately inside are stairs leading to her office—not downtown in a skyscraper, but upstairs in her home. Just as it mingled indoors and out, California modernism anticipated the reunion of home and work. Ayn Rand, before she decamped to the Empire State Building, wrote in a home office with a wall of glass accordion doors opening to the outside. Since 1950, Shulman has worked in a studio attached to the home designed for him by Soriano. With no commute, he still maintains an active work schedule. He is, he says, “always happy.”

And he is a perfect representative of the drive that shaped Los Angeles in the twentieth century and continues to give rise to new urban dreams. Los Angeles, like New York, was and is a “city of ambition,” the title of Alfred Stieglitz’s 1910 photo of a New York waterfront of towers and steam. But ambition takes a different form in California. West Coast ambition is not the upward thrust of a skyscraper, the drive to be the tallest in a small and crowded space. Californians like fame and money as much as anyone, of course. But (Hollywood agents aside) their dearest ambitions, like their architecture, are more horizontal, with room for everyone to erect an individual marker. This ambition may be less cutthroat, but it is, in its very openness, more universally demanding. Opting out of the quest for status or money is easy, even virtuous, compared with saying you don’t care whether your life leaves a mark. The things outsiders find absurd or threatening about California—the self-fashioned spiritual practices, the bodybuilder/action-star governor, the crazy diets, the junk bonds, the endless supply of new fictions, the UCLA- and Palo Alto–born Internet—do share a certain grandiosity, a ridiculous desire to change the world, or at least oneself. Better not to admit such ambitions, or so goes the fable easterners love to repeat: the story of the disillusioned California dreamer.

Storytelling, like photography, is a matter of selection and framing. The photographer Edward Weston “fell in love with stunning cracks in buckly plaster,” Neutra complained. “His wonderful photos could have served as evidence in court against a plastering contractor.” Understandably, the architect preferred Shulman’s idealized portraits. Both kinds of photographs were selective, yet also true. Shulman’s life and work remind us that some people do change the world, or at least their little piece of it. The photographer has not only crafted an oeuvre of more than a quarter-million prints, negatives, and transparencies. He has transformed the hillside behind his own modern home from bare dirt into a semitropical woods. “I’ve got a jungle,” he said proudly. “I made this myself.”

Elsewhere on the Web:

Julius Sherman, Modernity, and the Metropolis

The Web page of an exhibition at the Getty Museum. Includes photos and audio of Shulman discussing his work.