The iPhone of 1939 Helped Liberate Europe. And Women.

Bloomberg Opinion , October 25, 2019

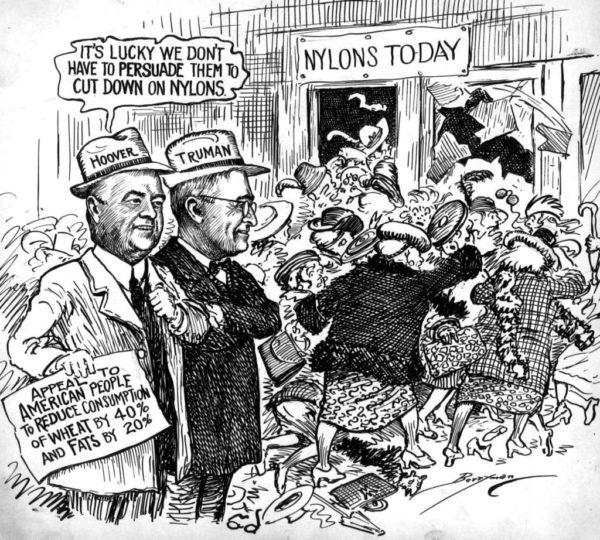

This week marks the 80th anniversary of one of the most successful and consequential product introductions ever. On Oct. 24, 1939, nylon stockings went on sale to the public for the first time. The frenzied reception was comparable to the one that greeted the original iPhone, and so were the long-term consequences.

“Customers were lined three deep at the counters most of the day,” reported the New York Times, noting that many buyers were men. The sale was merely a trial: 4,000 unbranded pairs sold by DuPont to demonstrate its new fiber’s real-world wearability. By 1:00 p.m., the six Wilmington, Delaware, stores offering them were completely sold out.

The stockings cost $1.15 to $1.35 ($21.09 to $24.76 in today’s dollars), depending on their sheerness, or about four hours of work at the minimum wage of 30 cents. When the national rollout took place the following May, about 800,000 pairs sold the first day.

Nylon’s inventor was a brilliant, troubled organic chemist named Wallace Carothers, who was hired by DuPont with the promise that he could research whatever he wanted to. He decided to investigate the nature of polymers, which many chemists believed were too large to be single molecules.

By 1931, his team had synthesized the first polyester and demonstrated that polymers were in fact regular molecules of extraordinary, theoretically unlimited, length. It was an enormous scientific achievement with no immediate commercial applications. Although it easily produced fibers, the new polyester melted at too low a temperature to be practical for textiles. After briefly trying different polymer components — amides rather than esters — Carothers turned to other research topics.

Nylon came about because DuPont broke its original promise of complete research freedom. As the Great Depression deepened, the company needed to show a return on its scientific investment. Carothers’s boss told him to figure out how to make a practical polymer fiber.

“Wallace, if you could just get something with better properties, higher melting point, insolubility, and tensile strength, you could have a new type of fiber,” he said. Why not revisit the polyamide research? After all, he noted, “wool is a polyamide.”

So beginning in early 1934, Carothers abandoned pure research and set out to make a polyamide that would tolerate hot water and dry cleaning fluid. After a few months of systematic trials, the lab had its first success: a silk-like filament that stood up to both. Further experiments found a way to synthesize it using benzene, a plentiful coal derivative, thereby making the new fiber affordable. By the end of 1935, the first nylon yarn was ready for testing.

Here we see the tricky balance that makes research management so difficult. Without the freedom to do fundamental research on the nature of polymers, nylon would have never been invented. Yet only by demanding that Carothers turn his attention to a more mundane, less scientifically appealing problem did the lab realize his research’s commercial potential.

From the start, DuPont knew that women’s hosiery would be a big market for its new fiber. It touted nylon stockings as a substitute for silk, boasting of the geopolitical implications of slashing Japan’s silk exports. “These may change the map of the world,” said an executive. Early sales mostly cut into the market for cheaper rayon and cotton stockings, however, giving silk stocking makers time to make the transition.

The new fiber did, of course, shape the map of the world. World War II temporarily diverted nylon away from consumer products to parachutes, glider tow ropes, tire cords, mosquito nets, and flak jackets. When Allied paratroopers dropped from the skies to launch the Normandy invasion, they unfurled nylon parachutes. Someone, perhaps an astute DuPont P.R. man, called the new synthetic the “fiber that won the war.”

DuPont made a deliberate decision not to promote nylon as “artificial silk” but, rather, as an exciting new synthetic made from “coal, air, and water.” The clear implication was that nylon was better than old-fashioned silk — stronger, more elastic, quicker drying, less likely to spot in the rain, more durable. Having promoted nylon as more resistant to snags than silk, the company had to damp down public expectations that the new stockings would never run.

Just as the iPhone defined a new device category, leading to competing smartphones, so nylon inspired similar synthetic fibers. After reading Carothers’s results, British chemists Rex Whinfield and James Dickson developed the fiber we know today as polyester, using the “less familiar and long neglected” terephthalic acid as an ingredient. They correctly hypothesized that its greater molecular symmetry would produce better results than Carothers’s polyester experiments.

Synthetic fibers fostered a fundamental shift in fashion expectations that continues to this day. “More than looks,” writes business historian Regina Lee Blaszczyk, “the characteristic that I call ‘high performance’ distinguished the panoply of postwar products from their early-twentieth-century predecessors….Curtains that could be drip dried, uniforms that never needed ironing, and sweaters that could be washed without shrinking reduced domestic burdens.” Comfort and convenience became paramount, and casual styles followed.

Nylons quickly became a synonym for women’s hose, including the pantyhose that supplanted garters and girdles in the era of miniskirts and women’s liberation — the latter made possible in part by synthetics that made keeping house a less than full-time job. Eventually, nylons, too, went out of style, supplanted by bare legs or, in colder temperatures, polyester-spandex tights and leggings. Today’s young woman is more likely to wear nylon in her sneakers or backpack than on her legs.

DuPont coined the generic term nylon but didn’t trademark it, reserving proper names for specific uses, such as the Exton toothbrush bristles that were the first nylon on the market, beating stockings by a full year. More even than stockings, those plastic bristles illustrate a technological truth that the iPhone’s makers are facing.

A thrilling new technology, if successful, is soon completely taken for granted. Incremental improvements will continue, but the excitement will dim. When was the last time you appreciated your toothbrush bristles for not absorbing water?