A Spam Title That Got Through My Filter

SELDON is great hogs of dull witted donkey when it was

SELDON is great hogs of dull witted donkey when it was

I'll be one of the judges for the 2007 Bottom Line Design Awards, sponsored by frog design and Business 2.0. But before we can start judging, we need nominees--and not just the usual suspects. Mick Malisic, the awards chairman, writes, "We're kicking-off the 2007 Bottom Line Design Awards, and are looking for nominations for great products, as well as people driving innovation at their company --- What innovators are truly re-thinking and changing the way we think about their industry? Who is using design as a business solution to raise the bottom line and capture the hearts & minds of consumers?" Use the form here to send in a suggestion, or email ideas to me at vp-at-dynamist.com. The 2006 winners are here. Thanks.

Garrison Keillor came to Highland Park, made nice to a big audience, and then wrote a snarky column about how Dallas-area Methodists are all a bunch of torture-supporting creeps. DMN columnist Jacquielynn Floyd explains. (Via D Magazine's FrontBurner blog.) The story adds another dimension to Keillor's famously nasty review of Bernard Henri-Levy's book on traveling through America. Project much, Garrison?

For the record, Professor Postrel and I spent quite a bit of time with BHL during his visit to Dallas, explaining such bizarre Americana as state flags and why Southern Methodist University hires Jewish professors. Fortunately, we didn't make it into the book. The truest line in Keillor's review is "Nobody sits and eats and enjoys their food." Not if they're eating with BHL anyway, since he's always either sending the food back because he doesn't like it or about to bolt away to another engagement.

What if there were a "cure" for skin color? It would be wildly controversial, right? Pundits would fill op-ed pages with analogies to X-Men 3: The Last Stand and occasional Mengele references. Unless, of course, the treatment were designed to cure people like me. National Geographic News reports on research that turns the fair-skinned authentically tan--at least if the fair-skinned are mice. Science writer Mason Inman says, "The tanning also protected the mice from UV radiation, and the level of protection made the tanned mice 'indistinguishable from genetically black-skinned mice,' [cancer researcher Dave] Fisher said."

A new kind of glamour is driving Silicon Valley dreamers, reports Erika Brown of Forbes--and it looks awfully familiar.

Forget engineers starting companies because they want to "change the world." Today's tech entrepreneurs seem to have a simpler goal: fame and fortune.

A few months ago, I interviewed Russel Simmons and Jeremy Stoppelman, who have raised $6 million to build Yelp, a Web site of amateur restaurant and bar reviews. (The two founders are in their late 20s, both single. They wear beat-up designer jeans with ironic T-shirts, and they have the kind of hair that forces them to flip their heads in order to see. In other words, rock stars.) At the end of the interview, I asked them where they thought they would be in five years. This is what they said:

Stoppelman: Sitting on top of a pile of money ... [in unison with Simmons] ... surrounded by women! Yeah! [high five]

According to Brown, they've already achieved one out of two.

It's no-doubt a character flaw, but I can't get emotionally involved with either the Hill's latest page-harrassment scandal (I'm afraid lecherous congressmen don't surprise me) or Terrell Owens's maybe-suicide attempt. Fortunately, Robert A. George, whose blog is becoming regular reading for me, has worthwhile thoughts on both, including some insider reporting on the mood among DC Republicans. And if you liked my superhero-glamour piece, don't miss his smart Memorial Day post on why major superheroes can't get divorced.

CORRECTION: The gracious Robert George notes that "the recent post about Terrell Owens was the work of this site's 'gridiron designated hitter' (to mix sports metaphors), Ed McGonigal!"

ADDENDUM: This is the libertarian New York Post editorialist Robert George, not the natural-law Princeton philospher Robert George. But surely you knew I wouldn't recommend the latter (not to mention the unlikelihood of Professor George blogging about comic books).

Courtesy of the wonderful Arts & Letters Daily, my Atlantic column on superhero glamour now has a permanent, free address.

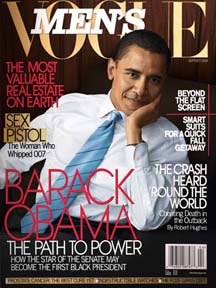

Men's Vogue has a tough editorial challenge. It's a fashion magazine for men that aims to attract a largely heterosexual audience. For its cover subjects, it needs men that other men find glamorous--that they admire for their seemingly effortless style, aspire to emulate, and do not resent. The first cover subject was George Clooney. The second was Tiger Woods. The most recent is Barack Obama.

Men's Vogue has a tough editorial challenge. It's a fashion magazine for men that aims to attract a largely heterosexual audience. For its cover subjects, it needs men that other men find glamorous--that they admire for their seemingly effortless style, aspire to emulate, and do not resent. The first cover subject was George Clooney. The second was Tiger Woods. The most recent is Barack Obama.

Obama's cover status is noteworthy. Senators are rarely style icons, and once upon a time the otherness of racial difference precluded glamour for a mass (i.e., white) American audience. "No white American, the [movie] industry maintains, would ever make his escape personality black," wrote Margaret Farrand Thorp in her 1939 book America at the Movies, one of the earliest analyses of modern glamour. As two out of three of the Men's Vogue covers illustrate, that has changed, mostly within the past decade. Nowadays, racial distance intensifies glamour by preserving the bit of mystery that true glamour requires. The distance is not so great to preclude projection, but it's great enough to prevent the intimacy (real or imagined) that would break the spell.

Writing in the New York Sun, John McWhorter considers why Obama's race is so central to his political appeal: "What gives people a jolt in their gut about the idea of President Obama is the idea that it would be a ringing symbol that racism no longer rules our land. President Obama might be, for instance, a substitute for that national apology for slavery that some consider so urgent. Surely a nation with a black president would be one no longer hung up on race." McWhorter's argument is correct as far as it goes, but it misses the apolitical glamour about Obama--and the mysterious Condoleezza Rice. That glamour depends on their race but is not solely about race, just as Jack Kennedy's glamour was not solely about wealth and Catholicism, though those characteristics made him a bit exotic to most Americans.

In response to my post on miniature cities, my friend Cosmo Wenman points me to another version of the same artistic impulse:

That article mentioned the appeal of tilt-shift photography: there are several flickr photo sets devoted to taking photos of real cityscapes and photoshopping them to look like scale models. The photoshopping reproduces what an antique tilting bellows/accordian type camera would do: it removes perspective distortion. That effect makes it looks like it was taken up close. Oversaturating the colors makes it look artificial.

Here are some good ones:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/miwo76/120735433/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mcsixth/106792657/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dnw/111587843/

And here's a delightful website devoted to "Little hand-painted people, left in London to fend for themselves." (Via CNet's Esoterica blog.)

"Governor Signs Bill Protecting Egg Donors" is the headline on this LAT article. A more accurate title would be "Governor Signs Bill Discouraging Egg Donors" or, mirroring the actual headline's bias, "Governor Signs Bill Exploiting Egg Donors." The new law forbids paying compensation to women who provide eggs for research.

The cover story of Reason's October issue is a first-person account by an egg donor, the magazine's associate editor Kerry Howley. Her story focuses less on regulation, which is minimal for U.S. fertility treatments, and more on the contradictory rhetoric surrounding "donation"--rhetoric that, I believe, helps explain why it's so easy to ban compensation when the ban won't run afoul of noisy, well-educated, affluent would-be parents. Here's a bit of the story's conclusion:

The strongest response to such opponents is not that IVF is natural or altruistic, but that it can be neither of those things without detracting from the dignity of the child-to-be. My experiences bear no resemblance to the nightmarish scenarios thrown out by those who portray egg donation as a clumsy eugenics scheme. Strip away the nexus of fertility doctor, donor agency, and donor, and two would-be parents were hoping for a kid who would look something like them. They weren't looking for a "designer baby," so much as a close approximation of the homegrown variety.

Before we ask IVF opponents to accept the implications of new reproductive technologies, though, we might ask the same of IVF supporters. From the recipient's side, the egg donor process can be an extended effort to pretend that the donation never occurred. Straddling the natural and the artificial, egg donation embodies a contradiction. It glorifies the experience of natural pregnancy and the gift of biological children, while it in fact produces neither: Egg donor babies are the product of foreign genetic codes, and the "natural" pregnancy is manufactured in the lab. The approximation of natural pregnancy also entails a studied psychological distance from the donor who made the pregnancy possible.

Opponents of IVF have long warned that the bond between mother and child will be eroded by further advances in assisted reproduction, the implication being that mothers will eschew the time and labor of traditional pregnancies once they can outsource to the lab. In practice, IVF seems to demonstrate the opposite extreme: Women value pregnancy to such a degree that they will spend lavishly to approximate the experience, adding expense, discomfort, and ethical quandary to the already burdensome ordeal of childbirth. The desire to stick to the traditional script of family is surprisingly robust, and reproductive technologies allow potential parents to follow that script even when nature erects barriers. Though IVF entails risk, discomfort, and the prospect of having to abort multiple fetuses, many parent apparently prefer it to what might seem a far less ethically complex response to infertility: adoption. Natural motherhood is not obsolescent, as The Atlantic once predicted, but ascendant, in vogue to an almost disturbing degree.

Those who worry reproductive technologies will destroy the family probably haven't had much contact with parents who will spend many thousands of dollars to create one. If there is a risk, it is that IVF might instead ossify the definition of family, stressing insularity above openness, the appearance of a "natural" pregnancy over adoption, genetic legacy over less rigidly defined familial bonds. For all the otherworldliness of egg donation, parents who choose the process cling to the traditional: children who appear to be their own, who are born through what appears to be a natural pregnancy. It's a bold new path to very familiar territory.