In the new issue of Cato Unbound, Theodore Dalrymple considers the question, with some insights into how stasis feeds more stasis. Replies will follow from Charles Kupchan, Timothy B. Smith, and Anne Applebaum.

What exactly is it that Europeans fear, given that their decline has been accompanied by an unprecedented increase in absolute material well-being? An open economy holds out more threat to them than promise: they believe that the outside world will bring them not trade and wealth, but unemployment and a loss of comfort. They therefore are inclined to retire into their shell and succumb to protectionist temptation, both internally with regard to the job market, and externally with regard to other nations. And the more those other nations advance relative to themselves, the more necessary does protection seem to them. A vicious circle is thus set up.

This is the third issue of Cato Unbound, edited by the very smart Brink Lindsey and Will Wilkinson. The previous issue featured a provocative, multifaceted essay by Jaron Lanier about the "Anti-goras" and "Semi-goras" that typify Internet commerce and the fundamentally cultural nature of the Net. If it were easy to summarize, it wouldn't be so valuable to read. If, like me, you missed it a month ago, check it out now.

Cato Unbound's format is an interesting experiment with fostering serious thought in a web-based publication and a refreshing alternative to the snarky quick bites so common in print and online. I look forward to reading more.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on February 05, 2006 • Comments

I suspect this WaPost article was planted by FDA employees looking for a bigger budget, but it raises an interesting issue: Why is it taking so long to approve generic drugs? Marc Kaufman reports that the current backlog, more than 800 applications, is an all-time high. Unfortunately, he doesn't explain what the approval process entails--How much testing does a generic require anyway?--or what it's supposed to achieve.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on February 05, 2006 • Comments

According to this LAT report by Seema Mehta, kids aren't learning penmanship anymore:

Educators say the days of primary school students hunched over desks and painstakingly copying rows of cursive letters are waning. There are many culprits: computers, a rejection of repetitive drills as a teaching tool, and government testing that determines a school's worth based on core subjects such as reading and math.

"Handwriting and cursive have been pushed aside," said Joe Mueller, principal of Litel Elementary School in Chino Hills. "When you have a student struggling and you have to pick an area to focus on, reading versus penmanship, reading [will prevail]. The plate is full."

Unfortunately, you can't always type, and test-taking in particular often requires legible writing.

But penmanship remains crucial to a student's success, [Vanderbilt professor Steve] Graham said. A prime example is the SAT's new timed essay section, which must be handwritten.

Though SAT graders are instructed not to let legibility influence how essays are scored, at least 10 studies have concluded that that's impossible, Graham said. A 1992 study of graders who had been so trained found that neatly written essays received the equivalent of a 2.5-point benefit on a 100-point scale. Among untrained graders, the advantage grew to more than four points.

The last time Professor Postrel was grading exams, I actually "translated" one particularly illegible one into writing he could read, saving an hour or so of grading time--and a lot of aggravation. Instead of cursive, however, why not teach kids to print neatly, ideally as precisely as architects?

Posted by Virginia Postrel on February 05, 2006 • Comments

A new site for obsessed authors and their loved ones. (Thanks to reader Jeremy Bencken.)

Posted by Virginia Postrel on February 03, 2006 • Comments

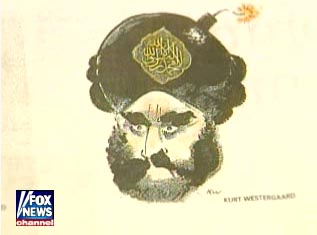

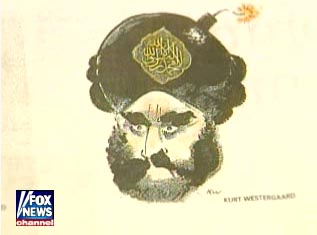

My response to this nonsense is to wonder why Muslims don't grow up. If your co-religionists are going to take political stands, and blow up innocent people in the name of Islam, political cartoonists are going to occasionally take satirical swipes at your religion. Those swipes may not be nuanced, but they're what you can expect when you live in a free society, where you, too, can hold views others find offensive. If you don't like it, move to Saudi Arabia. Or just try to peacefully convert people to Islam. As Fred Barnes points out, the current cover of Rolling Stone is offensive to (hypersensitive, paranoid, publicity-seeking) Christians, but they aren't threatening anyone with physical violence. (Here's an article on that.)

My response to this nonsense is to wonder why Muslims don't grow up. If your co-religionists are going to take political stands, and blow up innocent people in the name of Islam, political cartoonists are going to occasionally take satirical swipes at your religion. Those swipes may not be nuanced, but they're what you can expect when you live in a free society, where you, too, can hold views others find offensive. If you don't like it, move to Saudi Arabia. Or just try to peacefully convert people to Islam. As Fred Barnes points out, the current cover of Rolling Stone is offensive to (hypersensitive, paranoid, publicity-seeking) Christians, but they aren't threatening anyone with physical violence. (Here's an article on that.)

All of which is really just a lead-in to a plug for Jonathan Rauch's excellent book Kindly Inquisitors. Read it.

Read it.

The Fox News report from which the image above is taken is here.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on February 02, 2006 • Comments

Reader Eric Akawie writes in response to the item below:

I think another, somewhat unconscious motive behind Scrapbooking is the deprecation of the physical status of photographs. I remember as a child, photographs were absolutely sacred — we never threw away or cut up a photo, no matter how bad it was. But now, with photos printed at home, and so cheap individually, throwing photographs away is not a big deal (although I always feel a pang and sense my mother's disapproving glare.)

Scrapbooking returns that sense of specialness to the photos included, and with the amount of work (and money!) that goes into an individual page, acts as a bulwark against the photos being discarded during some cleaning/purging/simplifying binge.

The scrapbooking phenomenon reminds me of an observation made by Rose Wilder Lane in The Woman's Day Book of American Needlework , published in 1963. Lane, an important mid-century libertarian writer, is best known as the daughter of Laura Ingalls Wilder, whose Little House books she edited. Her needlework book combines some how-to advice with what would now be called feminist cultural studies. Her chapter on quilting emphasizes that "women created this rich needlework art who had not a penny to spend or a half-inch bit of cloth to waste." By contrast, the following chapter, on appliqué, highlights Hawaiian quilts which, like scrapbooking, were the product not of poverty but of unprecedented abundance: islanders with a kind climate and ample food who suddenly had access to steel pins and needles and mass-produced bolts of cloth. "You'd know that [Hawaiian appliqué] is up to date and then some, if you knew only one thing about it: it wastes cloth, lavishly," wrote Lane. "It wastes new cloth." When necessity ceases to be the mother of invention, as with patchwork quilts, the drive to create develops arts for their own sake.

, published in 1963. Lane, an important mid-century libertarian writer, is best known as the daughter of Laura Ingalls Wilder, whose Little House books she edited. Her needlework book combines some how-to advice with what would now be called feminist cultural studies. Her chapter on quilting emphasizes that "women created this rich needlework art who had not a penny to spend or a half-inch bit of cloth to waste." By contrast, the following chapter, on appliqué, highlights Hawaiian quilts which, like scrapbooking, were the product not of poverty but of unprecedented abundance: islanders with a kind climate and ample food who suddenly had access to steel pins and needles and mass-produced bolts of cloth. "You'd know that [Hawaiian appliqué] is up to date and then some, if you knew only one thing about it: it wastes cloth, lavishly," wrote Lane. "It wastes new cloth." When necessity ceases to be the mother of invention, as with patchwork quilts, the drive to create develops arts for their own sake.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on February 02, 2006 • Comments

My response to this

My response to this