Brains & Minds I: Brain Casualties

Michael Mason of Discover takes depressing look at one result of the military's remarkably effective battlefield medicine: an unprecedented number of war veterans who've survived with traumatic brain injuries.

Michael Mason of Discover takes depressing look at one result of the military's remarkably effective battlefield medicine: an unprecedented number of war veterans who've survived with traumatic brain injuries.

WindyPundit Mark Draughn posts a significant clarification to Tom Simon's good-hearted post about changes in the Illinois rules for deceased organ donors (see below). I'm afraid the state's organ procurement organization is using Tom (and me) in a disingenuous campaign. Mark writes:

What changed in Illinois is that your consent to donate your organs on death no longer requires the permission of your next of kin. The procurement team can simply look you up in the registry and take your organs without needing to get explicit permission from your family. They expect to get more organs this way because they can't be stopped by family members who are too distraught to make a decision. (I imagine they can even take the organs over your family's vigorous objections, but my guess is they'll be reluctant to do that.) Both Meis's message and the Donate Life Illinois website explain all this. However, their explanations imply that your consent to donate is invalid until you register, and that's not true.

If you're like me and you signed up as a donor before 2006 then you didn't agree to this new way of doing things. You agreed to donate your organs only with the consent of your next of kin. That has not changed in any way. If you die without re-registering, that will still happen. The procurement team will simply approach your next of kin for permission.

As someone sympathetic to the cause of organ donation, I'm appalled yet fascinated by the ethical contortions the organ establishment goes through while preaching the evils of any compensation for donors. They want more organs, but they hate having to ask for them--whether that means dealing with living donors, getting consent from family members (as in Illinois), or getting consent at all (the "presumed consent" approach, which requires people before they die to take steps to clearly refuse donation). Aside from the ethical problems of overriding a bereaved family's wishes and essentially declaring bodies the property of the state, there's a practical problem: These steps may sound attractive in the short run, but they sow long-run distrust of the system.

On a more positive note, also from Illinois, check out this article and this excellent short slideshow.

I like your example of abundance--a photo of dinner.

I've always liked renaissance still lifes of tables of food. Food was a natural subject for an artist--familiar, colorful, poseable (and still!), but I think those paintings conveyed a strong sense of the human-scale importance of a meal. The extravagance of commissioning an expensive, giant painting of a table overflowing with food must have been a really strong statement.

Cosmo makes a good point, one that I'll keep in mind next time I'm bored looking at slightly disgusting Dutch paintings of food. (As I mentioned earlier, I prefer architectural paintings, like this or these.)

"I especially like the ones with exotic seafood or with a pet that gets to share in the bounty," he concludes. Like these:

In his new book The Age of Abundance: How Prosperity Transformed America's Politics and Culture, Brink Lindsey argues that mass prosperity (by historical standards) fundamentally altered American political and cultural debates, shifting them from arguments over wealth distribution to more cultural/spiritual concerns. The "culture wars" are, in this view, a result of prosperity. I think he's basically right.

Certainly, anyone transported from the 1920s, or even the 1960s, would think we were living in a material paradise. But memories are short, people tend to romanticize the past, and expectations increase along with the standard of living. Luxuries like air conditioning or restaurant meals, even at fast food joints, become necessities.

Here's what I bought at the supermarket Monday for $6.00. (The minimum wage is $5.15 an hour.)

That's dinner for a family of four, or at least it was before portion bloat, and it's already prepared. A fried chicken was even cheaper.

We have so much stuff you can run a wildly successful and much-admired business selling boxes to put it in. In fact, these Container Store shoe boxes are stacked up waiting for someone I met through Freecycle to pick them up. We have so much stuff, people organize self-help networks to give it away. For more on Freecycle and "unconsumption" (or, perhaps more accurately, deconsumption), check out these posts from Steve Portigal's blog. (If you found my Forbes article on self-help networks interesting, be sure to check out Steve's posts, particularly the earliest one.)

We have so much stuff you can run a wildly successful and much-admired business selling boxes to put it in. In fact, these Container Store shoe boxes are stacked up waiting for someone I met through Freecycle to pick them up. We have so much stuff, people organize self-help networks to give it away. For more on Freecycle and "unconsumption" (or, perhaps more accurately, deconsumption), check out these posts from Steve Portigal's blog. (If you found my Forbes article on self-help networks interesting, be sure to check out Steve's posts, particularly the earliest one.)

Unlike some people, I don't see abundance as problem or a sign of decadence. I think it's great. But it does pose challenges. Just because you can have "everything" (not literally) doesn't mean you'll be happier if you do. And, as the Container Store's success suggests, the problems of sorting and storage become serious. I have no problem managing the shoes and clothes, but books are another matter. I haven't counted, but it's safe to say we have thousands, very few of them disposable. In late summer, we'll be moving back to L.A., and our place there is much smaller. Even with lots of Container Store products and consulting, I have to carefully scrutinize book acquisitions. So when I tell you I'm happy to add The Age of Abundance to my library, you should consider that a strong "Buy" recommendation.

Brink has also started (actually re-started) a blog at BrinkLindsey.com.

With captions and sound. [Via Very Short List.]

Tom Simon, Chicagoland's go-to guy on kidney donation, has updated his blog, with a post explaining why signing your driver's license won't make you an organ donor in Illinois. And he's got YouTube video of his local TV appearance.

"Where are You Mr. Pine?," wrote a reader named Steve Winslow on the Amazon page for Mr. Pine's Purple House back in March 2000.

I'm 32 years old with a 2 year old daughter and a boy due April 10th. For some strange reason I felt the need to look to see if this book was still out there. I'm touched that this book made such an impact in others lives as well as my own. Please reprint this book whomever has the rights to it, so my children and others may hear the tale of Mr Pines determination and perserverence in the face of peer pressure.

Later that year, Winslow and other fans of Mr. Pine got their wish. Thanks to an entrepreneurial publisher, Mr. Pine's Purple House was back in print. Since fall 2000, it has sold about 12,000 copies. In a short piece on The Atlantic's website (link good for three days), I tell the story of how that happened.

A not-very-brownstone, explanation here.

My latest Atlantic column (link good for three days) looks at neighborhood paint wars: If people care about the looks of not just their own house but the neighborhood as a whole, what do you do about nonconformists?

It's a difficult question that I dealt with in more depth--though with less colorful examples--in chapter five of The Substance of Style, excerpted here by Reason.

The geniuses in the Pentagon have decided that soldiers shouldn't be allowed to send emails or post to blogs without clearing the content with a superior officer. (And we know officers in the field have nothing better to do than play editor/flack.) The link above is to BlackFive (via InstaPundit), where there's lots more, including the Wired.com report that should set off a firestorm among people on every side of the war issue. Soldiers have the strongest incentives not to reveal operational details. So why hide their points of view?

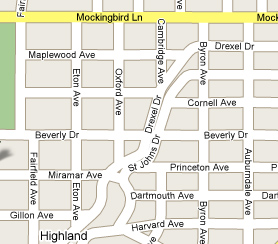

Do street names affect housing values? A fun, if unresolved, discussion on the Freakonomics blog. (The map is from Highland Park, the Beverly Hills of Dallas. The major artery north of Mockingbird Lane, back in Dallas proper, is Lovers Lane.)