Apparently the Postrels aren't the only ones who noticed that Chevrolet shows only the Impala logo, not the car, in its new TV commercials. They might as well come out and say it: HERE'S ANOTHER GENERIC CAR.

Cool logo, though. Very sleek.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on August 28, 2005 • Comments

The WaPost's Philip Pan reports on an extraordinary development in China: a class-action suit by rural villagers forced into abortions and sterilizations. The key argument in the case, which was organized by Chen Guangcheng, a self-taught legal activist, is that these coercive measures violate a 2002 law guaranteeing Chinese citizens "informed choice" in reproductive matters. The country's population-control policies are now supposed to rely on financial incentives, not physical threats and coercion.

The lawsuit is not just a human-rights crusade. It's a crucial test of China's commitment to the rule of law--a commitment that matters greatly to the country's economic development as well as its civil society. Pan's reporting suggests that central-government officials are at least saying the right things. Toward the end of the piece, which is well worth reading in its entirety, he interviews a central-government population-control honcho:

Yu Xuejin, a senior official with the national family planning commission in Beijing, said his office had received complaints about abuses in Linyi and asked provincial authorities to investigate. He said the practices described by the farmers, including forced sterilization and abortion, were "definitely illegal."

Yu emphasized that the central government had led the nation toward more humane family planning practices over the past decade. "If the Linyi complaints are true, or even partly true, it's because local officials do not understand the new demands of the Chinese leadership regarding family planning work," he said.

Yu also applauded the farmers for asserting their rights. If officials in Linyi violated the law, he said, "I support the ordinary people. If they need help, we'll help them find lawyers."

Posted by Virginia Postrel on August 28, 2005 • Comments

On a reporting trip to Detroit last week, I spent a spare hour (or, to judge from the parking ticket I got, a bit longer) at the Detroit Historical Museum. I was there to see a well-mounted exhibit of Supremes costumes from the collection of trio member Mary Wilson.

But while I was there, I naturally checked out the permanent exhibit on Detroit as "Motor City." I may be making too much of a single example, but the contrast between the Detroit exhibit and those I recently visited at the Petersen Automotive Museum in L.A. suggests a lot about what ails the Big Three. The Petersen is full of gorgeous automobiles. In Detroit, there was nary a car in sight. The car buyer barely seemed to exist. Cars had no glamour and no cultural significance. And car companies seemed to operate solely to provide jobs, attract people to Detroit, and spur the union movement. Nothing in the exhibit made you want a car. (The few vehicles on display were decidedly unattractive.)

At the Petersen, by contrast, the history--and there's plenty of it--is about innovation and social transformation. The car is a work of art and a source of personal expression. In California, cars are fun (despite all the traffic). In Detroit, they're drab artifacts of a black-and-white past. To be fair, the Ford and Chrysler museums do have cars on display; I just didn't have time for an extended museum tour. But you have to wonder about a Motor City that doesn't take every opportunity to demonstrate the appeal of cars.

By contrast, the Supremes exhibit, which included lots of Motown Records and civil rights history, not only showed the dresses (arranged on mannequins whose hand gestures were distinctively Supreme) but also played the music. It demonstrated why the Supremes were glamorous and successful. But it was organized by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, not the Detroit museum.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on August 28, 2005 • Comments

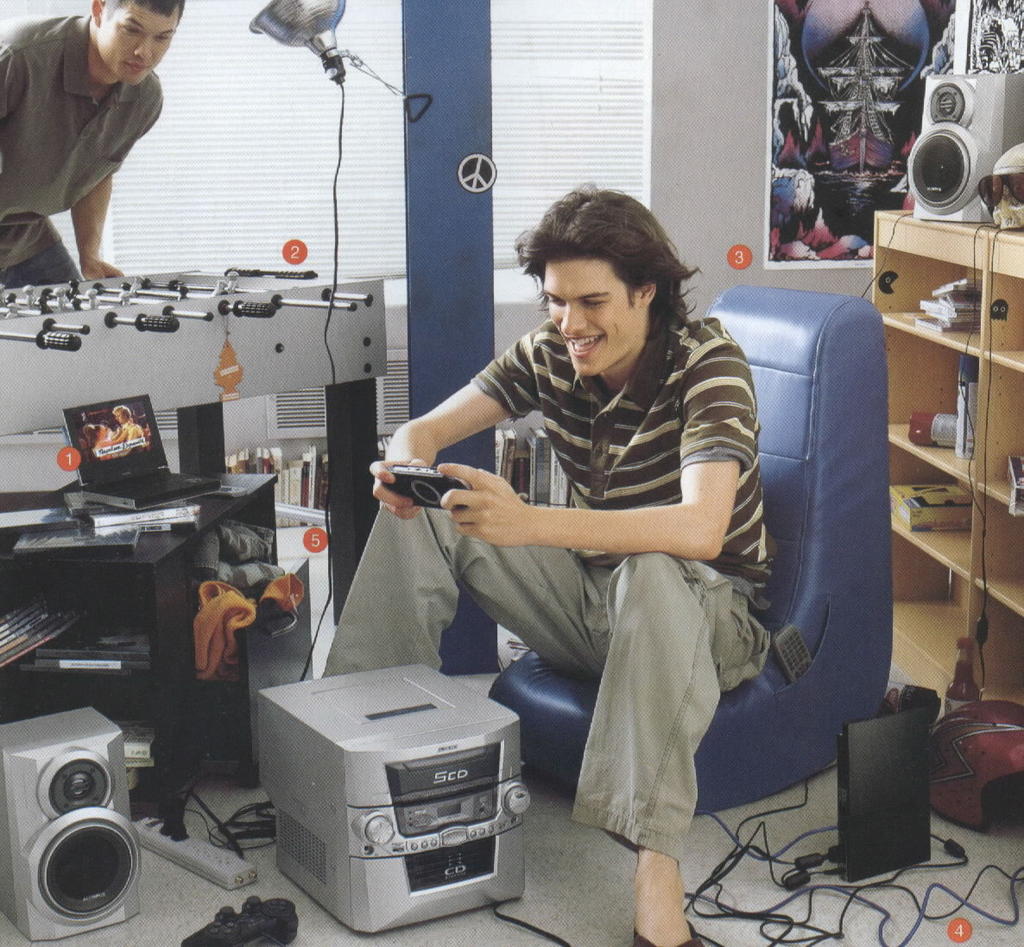

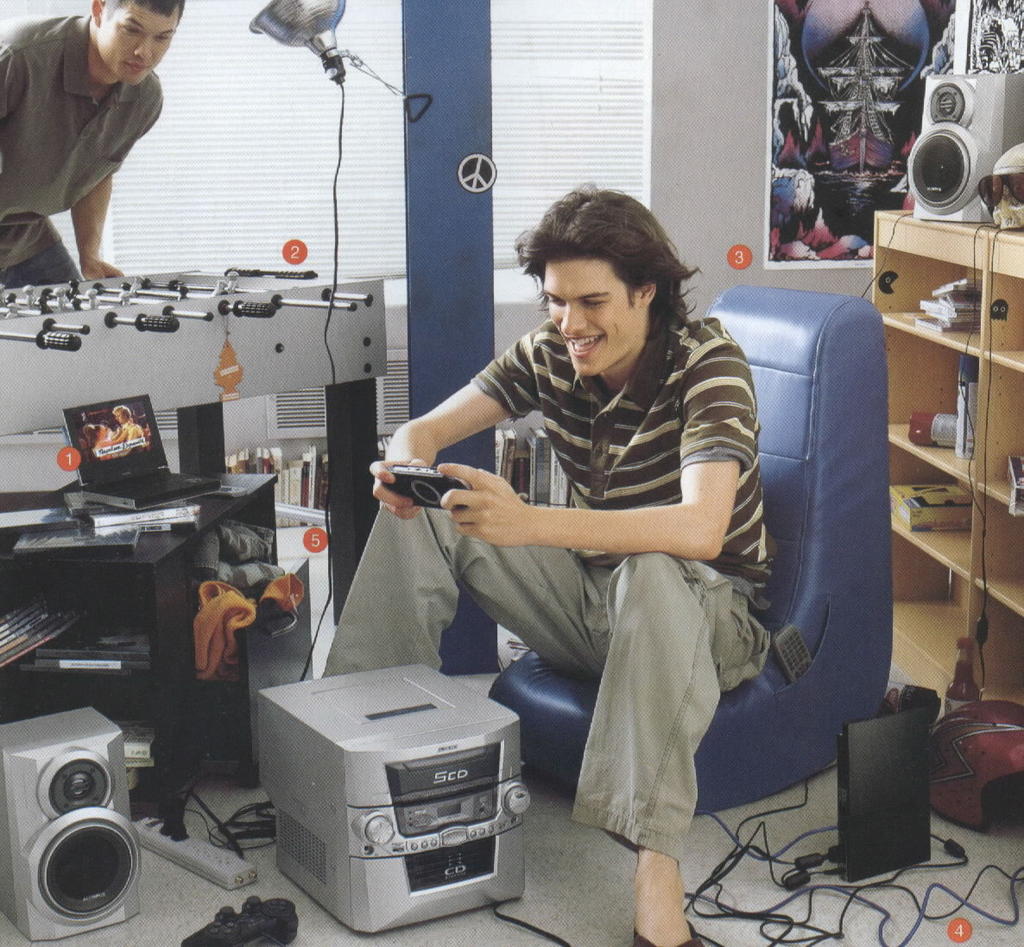

I recently discovered (thanks to an email from him) that Steve Portigal, who may be most familiar to readers from his frequent comments on Grant McCracken's blog, has his own blog. In a recent post, he called attention to a series of Target ads featuring extraordinarily messy and wire-filled rooms:

I was amazed to see pictures of messy rooms, where people own lots of stuff, it's messy, askew, and yes indeed, there are wires - cables, cords, the whole real deal.

Sure, the pictures are entirely stylized and sort of hyper-real, but somehow it's relieving to see a significant move away from the more idealized and yes glamourous consumer images that advertising is so fond of.

Whatever happened to wireless glamour? The same thing that tends to happen to every other kind of glamour: We got tired of it, because it was too much work. The grace, mystery, and idealism that give glamour its power aren't terribly compatible with everyday life, at least not the way most Americans want to live it. And when we're furnishing our homes (or our dorm rooms), we often prefer a comfortingly homey mess to glamour's impossible grace.

In his new book, Culture and Consumption II, Grant McCracken includes a chapter delving into the idea of "homeyness." (The short lead-in to this extended essay hilariously describes Grant's adventures as a guest on Oprah.) The ideas are too complex to summarize, but suffice it to say that homeyness is a desirable quality to many people and that it includes a lot of personal clutter:

Objects are homey when they have a personal significance for the owner (e.g., gifts, crafts, trophies, mementos, family heirlooms). A homemade ashtray assembled from shells collected on a summer holiday by the children served one family as a reminder of an important time and place in the history of the family and was therefore considered especially homey. Objects can also be homey when they are informal or playful in character (e.g., the novelty ashtray, a pillow in the shape of a football, a pillow with verse in needlepoint). Plants and flowers are objects that contribute to the homeyness of a room. Some objects are homey because they support or contain decorative objects (e.g., wooden hutches and what-nots)....Pictures of relatives, pets, and possessions are also homey. Paintings of certain kinds can have a homey character, especially sentimental treatments of landscapes or seascapes. Books in quantity can "furnish" a room and ggive it a homey character....

Respondents used a very particular set of adjectives to describe "homeyness." A favorite characterization of the homey place was to say that it looked "as though someone lived there." The terms "informal," "comfortable," "cozy," "relaxed," "secure," "unique," "old," "rich," "warm," "humble," "welcoming," "accommodating," "lived in," "country kitchenish" were all used as glosses...

The enemies of homeyness...were easily characterized. One respondent described an ornately formal living room as "cluttered up with a whole lot of fancy stuff" and therefore unhomey. The terms used to characterize unhomey homes were "pretentious," "formal," "stark," "elegant," "cold," "daunting," "sterile," "showpiece," "reserved," "controlled," "decorated," "modern," and even "Scandinavian."

Target is selling homeyness--of a youthful, technological sort--in those wire-filled ads. Glamour is the enemy of homeyness, so there's no need to hide the wires. (Just don't think about how you'd manage to walk across the room.)

Posted by Virginia Postrel on August 18, 2005 • Comments

The WaPost's Ariana Eunjung Cha reports on how Best Buy is tailoring the environment and service at particularly stores to appeal to specific types of customers. It's yet another sign that one-best-way store environments, like lowest-common-denominator products, just aren't as valuable--or aren't as competitive--as they once were.

Big chain stores used to be among the most egalitarian of places. They were aimed at the average person, the generic "shopper," without conscious regard to background, race, religion or sex. That is changing as computer databases have allowed corporations to gather an unparalleled amount of data about their customers. Many retailers, like Best Buy, are analyzing the data to figure out which customers are the most profitable -- and the least -- and to adjust their policies accordingly....

inspired by Columbia University Professor Larry Selden's book, "Angel Customers and Demon Customers," Best Buy chief executive Bradbury H. Anderson is on a mission to reinvent how the company thinks about its customers. Best Buy has pared some less desirable shoppers from its mailing lists and has tightened up its return policy to prevent abuse. At the same time, it has begun to woo a roster of shopper profiles, each given a name: Buzz (the young tech enthusiast), Barry (the wealthy professional man), Ray (the family man) and, especially, Jill.

Based on analyses of databases of purchases, local census numbers, surveys of customers and targeted focus groups, Best Buy last fall started converting its 67 California stores to cater to one or more of those segments of its shopping population. It plans to roll out a similar redesign at its 660 stores nationwide -- including about 15 in the Washington area -- over the next three years. The Best Buys in the Springfield Mall, the Fairlakes shopping center and Potomac Mills, for instance, are being transformed into stores for Barrys, featuring leather couches where one might imagine enjoying a drink and a cigar while watching a large-screen TV hooked up to a high-end sound system.

The Santa Rosa Best Buy, Store #120, is a Jill store.

Pink, red and white balloons festoon the entrance. TVs play "The Incredibles." There is an expanded selection of home appliances as well as new displays stocked with Hello Kitty, Barbie and SpongeBob SquarePants electronic equipment. Nooks are set up to look like dorms or recreation rooms where mom and the children can play with the latest high-tech gadgets at their leisure. Best Buy has new express checkout lines for the Jills; store managers say anyone can use them, but if you are not escorted by a special service representative they can be easy to miss. The music over the loudspeakers has been turned down a notch and is usually a selection of Jill's favorites, such as James Taylor and Mariah Carey.

Cha's piece is a good read. Don't rely on the excerpt. Read the whole thing.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on August 18, 2005 • Comments

Contrary to popular belief, the Kelo decision, terrible though it was, didn't really make new law. It ratified the status quo. For decades, cities have been taking private property under eminent domain, only to hand it over to private developers. The general public just had no idea how big the problem was until the Supreme Court said the practice was OK. Now politicians, including some who were previously fine with Kelo-style takings, are having to deal with a riled up public. The San Diego Union Tribune reports on one example:

Hit with scattered horror stories but convinced from her experiences on the San Diego City Council that eminent domain can be a valuable tool for progress, state Sen. Christine Kehoe says it's time to rethink how local governments use — and sometimes abuse — their broad powers of condemnation.

The San Diego Democrat has introduced legislation that includes an immediate two-year moratorium on seizing owner-occupied housing under the banner of eminent domain.

In doing so, Kehoe aligns with a growing number of lawmakers — both liberal and conservative — who are demanding a fresh look at eminent domain after a 5-4 U.S. Supreme Court decision that upheld a Connecticut city's right to evict middle-class homeowners to pave the way for a waterfront hotel and convention center to support a $300 million research facility for Pfizer.

In the Sacramento Bee, Claire Cooper surveys proposals, including Kehoe's fairly wimpy one, to change California law to give property owners a bit more protection. There's a dispute, she notes, over how widespread the takings are.

Timothy Sandefur, representing the Pacific Legal Foundation, testified that California agencies condemn private property to benefit private developers "eight times as often" as Connecticut agencies do.

Michael Berger, a Los Angeles lawyer, said the statistics on condemnations have been understated, because most property owners sell out to redevelopment agencies before condemnation proceedings are instituted against them.

But Sacramento attorney Joe Coomes, testifying for the California Redevelopment Association, said redevelopment projects in the state rarely include residential neighborhoods.

He and Bill Higgins, a land-use expert associated with the League of California Cities, warned against passing new laws that might hobble vital infrastructure projects and the ability of cities to clean up contaminated properties where owners refuse to take responsibility.

Focusing on the threat to owner-occupied homes may, indeed, miss the point. When people lose their businesses to redevelopment schemes, they aren't all that much happier.

Here in Texas, I note that my former colleague Rich Phillips, who did a stint as the Reason Foundation's public affairs director, is running for the state legislature and, judging from his website, he's making Kelo a central issue. Amid the usual boilerplate about supporting education, prosperity, and families is the following strong and specific statement:

The U.S. Supreme Court recently ruled that local governments may seize people's homes and businesses. As a result, cities now have the power to bulldoze your home for private development such as shopping malls and hotel complexes to generate more tax revenue. The ruling is a signal that we need to have the courage and will to defend our core principles and values. This is not America. And this is not Texas.

I doubt that Rich will be the only candidate to make this an issue, in Texas or elsewhere.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on August 18, 2005 • Comments

Bush's Aid Cuts on Court Issue Roil Neighbors

Unless you click to the story, you'll never figure out what it means. Or at least I couldn't.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on August 18, 2005 • Comments

My latest NYT column takes a (fairly cursory) look at research incorporating the sociological notion of identity into economic models. The column, which draws on papers I read while researching my Globe article on economic sociology, came out last Thursday, while my Internet access was rather limited.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on August 15, 2005 • Comments

Women are born with all the eggs they'll ever have, and after puberty, they start to discard at least one a month. As they reach middle age, they run out. When a woman of my advanced age, or, say, Elizabeth Edwards', has a baby, chances are very, very high that she used another woman's egg--especially if the baby is her first. Unlike adopting a child or using a surrogate, however, using an egg donor means you get pregnant and bear the child yourself. And that means you can pretend no donor was involved, which is exactly what a lot of people do.

Writing in the new issue of Elle, Nancy Hass looks at the ethical problems created by this vast conspiracy of silence. It's a long and well-researched piece and, fortunately for those of you who wouldn't be caught dead carrying a magazine with J.Lo on the cover, it's online. Here's a statistical bit:

You may have assumed that telling a child she's the product of another woman's egg mixed with Daddy's sperm in a petri dish would be obvious. Our society, after all, is increasingly obsessed with DNA and the influence of heredity, and we've come to believe that children have a right to know their genetic background. Until the 1960s, it was common to pass off adopted children as one's own; today, it's almost unthinkable. Add to that decades of movies and books warning of the danger of "toxic" family secrets and our collective experience of watching adoptees search the globe for their birth parents, and you might think that few among us would choose not to inform a child that half of his or her genes came from a woman whose name is sitting in a doctor's file across town.

You would be wrong. Since 1984, when the first egg donor baby was born in Australia, more than a million such children have been born worldwide, nearly 250,000 of them in the United States. But as the first generation of these children becomes teenagers, researchers predict that more than half of their parents will try to keep the secret in perpetuity. In a 2004 study of 157 couples, a third of the parents adamantly opposed telling; 18 percent couldn't agree on a plan, though some of the children in the study were as old as eight. Fewer than 20 percent of parents already had leveled with their son or daughter, and while a third indicated that they intended to eventually, the researchers say they doubt all of them will follow through.

And this report probably overstates parents' openness. Coauthor Susan Klock, a Northwestern University psychologist, says that the response rate to her questionnaire — 30 percent — speaks volumes. "Of the 70 percent who won't talk, you'd be safe in assuming that the majority of them aren't planning to tell."

Hass quite naturally concentrates on the personal dilemmas: What happens if a child discovers the deception? How many deceptions do you have to layer on top of the primary one to preserve it?

But there's also a huge public policy issue here. Particularly from the anti-biotech left, banning payments to egg donors is one of the primary ways of stopping research that requires human eggs, notably therapeutic cloning. Where religious arguments against embryo research don't succeed, anti-commercial ones can. Canada's draconian law against cloning includes provisions that will essentially wipe out egg donation at fertility clinics. Donors are allowed only "documented expenses," with no compensation for the enormous trouble.

As long as people think egg donation is a freaky, unimportant activity, laws like this are all too easy to pass. The conspiracy of silence makes egg donation look much rarer--and far more shameful--than it actually is. For people to get used to strange new technologies, they have to like, or at least adapt to, the consequences of those technologies. People like all these babies; society has certainly adapted to their births, with minimum dirsuption. But egg donation still sounds strange, because too many mothers and fathers pretend it isn't happening.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on August 15, 2005 • Comments

After many years of bureaucratic resistance, California is finally getting serious about air pollution from cars. These days, most cars don't spew much pollution. But the few that do, account for a lot, and many of them still manage to pass state inspection. Now, the LAT reports, the state is rolling out a serious program to measure tailpipe emissions of cars actually on the road:

In the largest experiment of its kind in California, the South Coast Air Quality Management District plans to use remote sensors and video cameras to measure air pollution from 1 million vehicles as they enter freeways and navigate roads in the counties of Los Angeles, Orange, San Bernardino and Riverside.

If caught, the owners of the most environmentally offensive cars and trucks would receive letters informing them that the government would pay to fix or scrap their vehicles. The South Coast district estimates that 10,000 to 20,000 of the dirtiest vehicles would be detected. Smog regulators lack the authority to order drivers to dump dirty cars, but they can offer incentives

California officials estimate that the dirtiest 10% of all cars and trucks — mostly older vehicles — spew out roughly 50% of the state's smog-forming emissions from vehicles. By the end of this decade, three-fourths of emissions from vehicles will be from older cars and trucks, state officials estimate.

Studies have shown that scrapping high-polluting vehicles is among the most cost-effective ways of cleaning the air — far cheaper than additional controls on power plants and refineries. Yet politicians and state officials have failed for years to get the dirtiest cars off the streets.

"You can't meet our air quality goals without addressing this problem," said Victor Weisser, chairman of California's Inspection and Maintenance Review Committee, which oversees the state's smog-check program.

Remote sensing ought to completely replace garage-based smog tests, though that's a tough political battle. (Garages make a lot of money from those largely symbolic tests.) Just getting remote sensing adopted, even in a large-scale experiment, has been very, very tough. My friend and then-colleague Lynn Scarlett described just how difficult in a 1996 Reason article drawing on her experiences as chair of the Inspection and Maintenance Review Committee. Here's a bit of it:

Its champions see the smog dog [the cutesy name for remote sensing--vp] as an easy way to identify gross polluters without putting everyone through some kind of test. They also see the smog dog as an answer to the "clean for a day" problem. If people know they might be nabbed by the smog dog, they may be more mindful of keeping their cars in better working order to avoid a fix-it ticket or other penalties. But the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency won't allow California (or other states) to rely just on the smog dog. In part, this is because current remote sensing technology does a poor job of measuring nitrogen oxide emissions, which make up a key smog-forming gas. A smog dog to measure NOX is already under way, however, and measuring NOX may not be that important anyway. Many gross polluters fail for all major emission gases.

The bigger dispute is more fundamental. EPA officials seem to think that all cars, not just gross emitters, need to be tested no matter what--and fixed to manufacturer operating standards--if smog check programs are to bring about substantial emission reductions. The smog dog, they say, is not up to the task of testing every car on the highway.

This raises a philosophical more than a technical issue. Just how clean is clean? Is targeting and cleaning up the dirtiest 10 percent of vehicles enough? Air-quality research scientist Douglas Lawson, a former consultant to California's Inspection and Maintenance Committee, argues that getting the really dirty cars is a big enough challenge in itself--and, he argues, that's where the smog check ought to focus. That's where large emission reductions per dollar spent are possible. Out at the margin--where cars are just a little bit dirty--test and repair costs often remain just as high as for gross polluters. But dollars spent on these cars produce few, if any, emission reductions. Often, tinkering with these more marginal polluters actually results in no emission reductions. Sometimes, as Lawson found when reviewing a California Air Resources Board pilot project, these cars produce even more emissions after so-called repairs than before.

When presented with these arguments by California's Inspection and Maintenance Review Committee, EPA officials were unconvinced. And their opinion matters. It's the EPA that doles out emission-reduction credits to states. States that don't get enough credits (which have nothing to do with real-world, measurable emission reductions) for their clean air programs face all kinds of potential penalties. Some California motorists may resent the new smog check program. But it's the least-intrusive plan the state could implement and still meet EPA requirements. Without a rigorous smog check program, drivers could face odd-even driving day regulations. And the state could face restrictions on operations at the Port of Los Angeles and Los Angeles International Airport, or other similarly draconian measures.

Remote sensing is about cleaning up the air, not changing lifestyles or collecting a general tax on cars. It doesn't make any interest groups rich, and it reminds (some) drivers that they, not anonymous big corporations, are now the major sources of smog.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on August 15, 2005 • Comments