Signs of the New China: Shanghai, May Day 2010

Barry Schwartz would not approve.

This quotation is supposedly from John Adams, but I think something got lost in translation. The store sells preppy kids' clothes.

Barry Schwartz would not approve.

This quotation is supposedly from John Adams, but I think something got lost in translation. The store sells preppy kids' clothes.

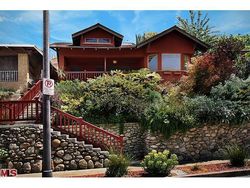

Meghan Daum's new book Life Would Be Perfect If I Lived in That House

Meghan Daum's new book Life Would Be Perfect If I Lived in That House breaks from a long-standing trend in nonfiction publishing. Instead of a clever title followed by a long explanatory subtitle, it has no subtitle at all. It doesn't need one, because the title itself so perfectly encapsulates a common, but rarely articulated longing. The book is all about the intense glamour of houses you don't have. I review it in Tuesday's Wall Street Journal. Here's the beginning of the review.

For all the esoteric talk of tranches and credit-default swaps, the recent financial meltdown began with something far more primal: house lust and its accompanying dreams and delusions. "There is no object of desire quite like a house," writes Meghan Daum, a columnist for the Los Angeles Times. "Few things in this world are capable of eliciting such urgent, even painful, yearning. Few sentiments are at once as honest and as absurd as the one that moves us to declare: 'Life would be perfect if I lived in that house.' "

The fantasy of a life transformed is what makes the ads and features in interiors magazines so enticing — no fashion or celebrity magazine glamorizes its subjects as thoroughly as Architectural Digest or Elle Decor — and what gives HGTV's low-budget shows their addictive appeal. The longing for the perfect life in the perfect environment can make real-estate listings and "For Sale" signs as evocative as novels. This domestic ideal gives today's neighborhoods of foreclosed or abandoned houses their particular emotional punch. A stock-market bubble may create financial hardship, but a housing bust breaks hearts.

Although Ms. Daum did buy a house in 2004 and watched its value rise and then fall, her self-deprecatingly funny memoir isn't a tale of real-estate speculation. Rather she uses her lifelong obsession with finding the ideal living space to probe domestic desire, a deeper restlessness than the search for quick profits.

Read the rest here. You can buy the book here.

[Los Angeles Craftsman house for sale from Redfin via Curbed L.A.]

Sheena Iyengar is the psychologist responsible for the famous jam experiment. You may have heard about it: At a luxury food store in Menlo Park, researchers set up a table offering samples of jam. Sometimes, there were six different flavors to choose from. At other times, there were 24. (In both cases, popular flavors like strawberry were left out.) Shoppers were more likely to stop by the table with more flavors. But after the taste test, those who chose from the smaller number were 10 times more likely to actually buy jam: 30 percent versus 3 percent. Having too many options, it seems, made it harder to settle on a single selection.

Wherever she goes, people tell Iyengar about her own experiment. The head of Fidelity Research explained it to her, as did a McKinsey & Company executive and a random woman sitting next to her on a plane. A colleague told her he had heard Rush Limbaugh denounce it on the radio. That rant was probably a reaction to Barry Schwartz, the author of "The Paradox of Choice" (2004), who often cites the jam study in antimarket polemics lamenting the abundance of consumer choice. In Schwartz's ideal world, stores wouldn't offer such ridiculous, brain- taxing plenitude. Who needs two dozen types of jam?

That's the opening to my review of Iyengar's The Art of Choosing in today's NYT Book Review. Read the rest here. My fullest treatment of the questions of choice appeared in this Reason article, which anticipated many points made in Iyengar's book. See more of my work on the "variety revolution" here.

After C-SPAN reran a 1999 BookNotes interview about my first book, I received an email from a disappointed viewer. He was chagrined to hear that I was editing a website called DeepGlamour instead of writing "more serious nonfiction." Glamour, he implied, is a trivial subject, unworthy of consideration by people who watch, much less appear on, C-SPAN.

After C-SPAN reran a 1999 BookNotes interview about my first book, I received an email from a disappointed viewer. He was chagrined to hear that I was editing a website called DeepGlamour instead of writing "more serious nonfiction." Glamour, he implied, is a trivial subject, unworthy of consideration by people who watch, much less appear on, C-SPAN.

To which I have two words of response: Barack Obama. In an era of tell-all memoirs, ubiquitous paparazzi, and reality-show exhibitionism, glamour may seem absent from Hollywood. But Obama demonstrates that its magic still exists. What a glamorous candidate he was — less a person than a persona, an idealized, self-contained figure onto whom audiences projected their own dreams, a Garbo-like "impassive receptacle of passionate hopes and impossible expectations," in the words of Time's Joe Klein. The campaign's iconography employed classically glamorous themes, with its stylized portraits of the candidate gazing into the distance and its logo of a road stretching toward the horizon. Now, of course, Obama is experiencing glamour's downside: the disillusionment that sets in when imagination meets reality. Hence James Lileks's recent quip about another contemporary object of glamour, "The Apple tablet is the Barack Obama of technology. It's whatever you want it to be, until you actually get it."

As critics who denounce movies that "glamorize violence" or "glamorize smoking" understand, glamour is much more than style. It is a potent tool of persuasion, a form of nonverbal rhetoric that heightens and focuses desire, particularly the longing for transformation (an ideal self) and escape (in a new setting). Glamour is all about hope and change. It lifts us out of everyday experience and makes our desires seem attainable. Depending on the audience, that feeling may provide momentary pleasure or life-altering inspiration. Read the rest, a longish review-essay, at The Weekly Standard.

As John Scalzi has scathingly noted, Amazon really screwed up when they pulled all of Macmillan's titles from their site. Although I think they have the right idea about book prices, they betrayed their customers' expectations and, worse, did so without warning. They forgot that Amazon is what Professor Postrel called in this 2007 post on Organizations and Markets a "new-wave utility" and, a such, has adopted a strategy that implies a high level of reliability.

How do you get sustainable advantage in a service business today? One approach: Become a new-wave utility. Think about Google or Yahoo, eBay, Amazon, etc. on the Internet; think about UPS or FedEx, Grainger, Ryder, Public Storage in logistics; think about McDonald's, Starbucks, 7-Eleven, in convenience food consumption.

To see the implications, read the whole thing.

Amazon has backed down from its weekend dispute with Macmillan, agreeing to charge the publisher's higher prices for Kindle editions rather than its preferred $9.99. But the long-term questions about e-book pricing remain.

Amazon still calls Macmillan's prices--generally $12.99 to $14.99 for new books--"needlessly high." Apple, meanwhile, has made deals with publishers like the one Macmillan demanded from Amazon: higher prices for books, with Apple keeping a percentage of sales.

Who, in fact, has the better strategy? To maximize revenue, what should prices for e-books look like?

Read the rest at TheAtlantic.com.

All this week on DeepGlamour.net we're featuring excerpts from Stephen G. Bloom's new book, Tears of Mermaids: The Secret Story of Pearls, which uses a tour of the pearl industry as a microcosm of the global economy. Here's today's post:

In Tears of Mermaids: The Secret Story of Pearls

, Stephen G. Bloom (interviewed yesterday) provides a behind-the-scenes tour of the worldwide pearl industry. Here is the first of four installments on the Chinese freshwater pearl farms that are transforming the world of pearls.

Zhuji (pronounced SHOE-ghee), about 100 miles southwest of Shanghai in the province of Zhejiang, is the epicenter of the world's freshwater pearl market. These are cultivated pearls that don't come from oysters, but instead from large, oval-shaped mussels. China produces 99 percent of all such freshwater pearls in the world. Zhejiang province is dotted with thousands of small, family-operated pearl farms, most of them state cooperatives. Such farms are seemingly everywhere, with millions of green plastic pop bottles bobbing up and down on the surfaces of thousands of small artificial lakes, each bottle signifying another crop of fresh mussels, and each mussel containing as many as fifty pearls inside. Exactly how the Chinese have been able to cultivate mussels that produce so many pearls remains something of a mystery. These pearls don't develop around an inserted nucleus, as their counterparts in oysters do, but instead grow from multiple tiny squares of mussel mantle tissue inserted into each host mussel.

The first crop of Chinese freshwater pearls appeared in the early 1970s, and since then, pearl exports from Hyriopsis cumingii mussels have grown exponentially. At first, the pearls were miniscule. By the 1980s, their size had grown and they started coming in a variety of striking rainbow colors. These pearls were often labeled and sold as Lake Biwa or Lake Kasumigaura pearls from Japan, fetching higher prices because of the Japanese label.

The Chinese freshwaters were a breakthrough in the fashion marketplace. Fashion-conscious women around the world started wearing pearls that weren't just white or cream-colored, and not always round. Stylish younger women gravitated to them. These pearls had four things going for them: they were colorful, they often weren't symmetrical (the baroque shapes appealed to non-traditional pearl wearers), they had the legitimacy of being real pearls, and they were downright cheap when compared to traditional pearls. As their size got larger, the Chinese freshwaters readily turned into trendy fashion items, turning into accessories fashion-forward women in their twenties and thirties from Paris to São Paulo just had to have. It didn't hurt that women like Meryl Streep, Jennifer Aniston, and eventually Michelle Obama started wearing them, too.

As Chinese technology got better, more and more freshwater pearls came on the global market at a fraction of the price of their international counterparts. By the late 1990s, the best of the Chinese freshwaters were virtually undetectable from increasingly scarce Japanese akoyas, and soon, the Chinese pearls were available in even larger sizes than the Japanese species would allow. Symmetrical freshwater Chinese pearls now come as large as 14 millimeters (that's as big as a marble), and are getting larger. Their skin can be flawless and comes in a multitude of colors (pink, blue, violet, orange, gold, gray), some right out of the shell, others the result of dye, chemical, and radiation treatments.

The flooding of so many Chinese pearls into the world market presented a problem for producers of more expensive pearls (just about every producer outside China). It'd be akin to the De Beers diamond syndicate discovering a competitor had come up with a new process that could create a genuine diamond, not a zirconium knockoff, but a real diamond that cost pennies to the thousands De Beers diamonds fetch. No wonder the worldwide pearl industry started screaming.

Example: A strand of medium-sized, near-perfect Chinese freshwater pearls can be bought wholesale today for under $150. Such reverse sticker shock is freaking out just about every other national producer of pearls. To make matter worse, to most consumers, such a strand is virtually identical to strands that sell for five and ten times as much (and sometimes more). Chinese freshwaters are showing up everywhere, from top-end retail jewelry boutiques like Mikimoto, Bulgari, Harry Winston, and Van Cleef & Arpel's to low-end merchandizing giants, such as Wal-Mart, JC Penney, Jeremy Shepherd's Internet sites, and cable TV's QVC. Their price-point is so low and their quality can be so high, that it's no surprise that some dealers intentionally mislabel Chinese strands as of a more expensive provenance (Japanese, Tahitian, even Australian). This can be by unscrupulous intention, but it's often just an uninformed mistake. Chinese pearls can look so good they fool wholesalers and retailers alike.

Inexpensive high-quality Chinese pearls are out there, and out there in a big way, and because of their proliferation, the global pearl industry is undergoing the same cataclysmic changes it faced in the 1930s, when Japanese cultured pearls were introduced to world markets. The rapid abundance of cultured pearls devastated and soon destroyed the natural-pearl market. Some dealers say today that the same could happen with Chinese freshwater pearls, ultimately replacing their much more expensive seawater counterparts from around the world. I wanted to see how the Chinese were going to make this happen.

Next installment here: Zhuji and visiting a pearl farm

[Pearl farm and baroque pearls photos by Stephen G. Bloom. Freshwater pearl necklaces from Yiwu Disa Jewelry Co., Ltd.]

---Buy Tears of Mermaids here---

And it's pretty cool (no pun intended).

He comes across as the typical, literal-minded geek, missing the appeal of visual wonder. But he gets this right:

That vertical city of the future we know now is, to put it mildly, highly improbable. Even in New York and Chicago, where the pressure on the central sites is exceptionally great, it is only the central office and entertainment region that soars and excavates. And the same centripetal pressure that leads to the utmost exploitation of site values at the centre leads also to the driving out of industrialism and labour from the population center to cheaper areas, and of residential life to more open and airy surroundings. That was all discussed and written about before 1900. Somewhere about 1930 the geniuses of Ufa studios will come up to a book of Anticipations which was written more than a quarter of a century ago. The British census returns of 1901 proved clearly that city populations were becoming centrifugal, and that every increase in horizontal traffic facilities produced a further distribution. This vertical social stratification is stale old stuff. So far from being 'a hundred years hence,' Metropolis, in its forms and shapes, is already, as a possibility, a third of a century out of date.

People are still refusing to believe those 1901 census results: "Real" cities look like Metropolis, not London.

[Hat tip: Paleo-Future Twitter stream.]

ADDENDUM: Reader William Krause of LikeTelevision sends this link to an online version of Metropolis. He also notes that "HG Wells made his own end of the world, life sux movie...called Things to Come...with Sir Ralph Richardson," available here.