The recession is bad and probably will get worse, but historical context doesn't scream Great Depression. Journalists, who are like steelworkers in the 1980s, can be forgiven for thinking the economy is collapsing--we're all afraid of losing our jobs--but the rest of you should know better.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on December 21, 2008 • Comments

Katherine Mangu-Ward offers political relationship advice. I don't want to spoil it, so just go read it.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on December 21, 2008 • Comments

A thoughtful post by Jim Manzi.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on December 19, 2008 • Comments

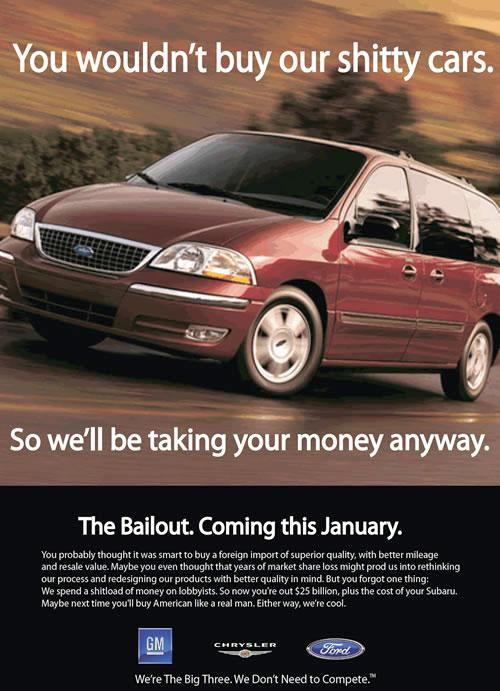

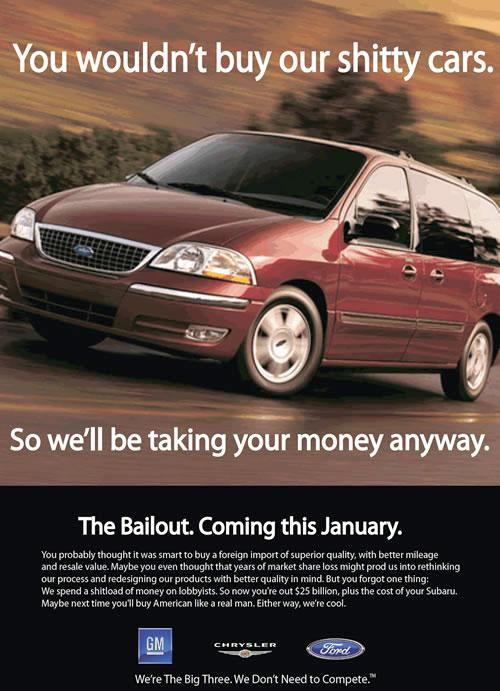

Not entirely fair to Ford, but point well taken. [Via The Wine Commonsewer.]

Posted by Virginia Postrel on December 15, 2008 • Comments

A D.C. friend told me that publicity-chasing attorney Gloria Allred, whose litigation took gay marriage out of the legislature (where it passed twice) and into the courts and who was quick to file a suit to overturn Prop. 8, gave not a dime to the campaign against Prop. 8. So I went to the searchable database and, sure enough, she's nowhere to be found. I tried every search I could think of. (Search yourself, and if you find her, I'll be happy to correct the record.) I guess there weren't enough TV cameras on the contribution site.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on December 13, 2008 • Comments

Sam Macdonald, a former Washington editor for Reason and author of the new book The Urban Hermit: A Memoir , emails in response to my Depression lust post below:

, emails in response to my Depression lust post below:

I just wrote a book (released November 25) about my own experience with starvation. Long story short, I was really fat and really broke after college, so I decided to live on 800 calories a day. I ended up losing 160 poounds and, eventually, digging myself out of debt.

I wrote the thing when the economy seemed rather strong. So it was never supposed to be "timely." But now it's intereting to see the way the media is reacting. For instance, here's a review in the LA Times stating that the timing is "... uncanny..." That is, that there are lessons for people to learn.

On the other hand, here's someone from Time magazine saying that the book WOULD be funny and interesting, but the timing is awful, somehow making it not funny anymore.

In my mind, and in my experience, hunger sucks. I much prefer plenty. But I guess that's just me being a libertine. Or some such.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on December 07, 2008 • Comments

Check out the ideas at DeepGlamour.net.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on December 06, 2008 • Comments

Economists Mark Bils and Pete Klenow, two very smart and interesting guys, argue (via an email to Greg Mankiw) for cutting the payroll tax as an economic stimulus. For reasons similar to theirs, that was my idea for stimulus during the previous recession in 2001. I was supposed to talk about it on the Newshour, but the appearance was scheduled for September 11.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on December 06, 2008 • Comments

Judging from the results in the far-more-predictable circumstances of lab experiments, it seems so. My new Atlantic column looks at the research:

In these uncertain economic times, we'd all like a guaranteed investment. Here's one: it pays a 24-cent dividend every four weeks for 60 weeks, 15 dividends in all. Then it disappears. Unlike a bond, this security has no redemption value. It simply provides guaranteed dividends. It involves no tricky derivatives or unknown risks. And it carries absolutely no danger of default. What would you pay for it?

Before financially sophisticated readers drag out their calculators, look up interest rates, and compute the present value of those future payments, I have a confession to make. You can't buy this security, and it doesn't really pay dividends every four weeks. It pays every four minutes, in a computer lab, to volunteers in economic experiments.

For more than two decades, economists have been running versions of the same experiment. They take a bunch of volunteers, usually undergraduates but sometimes businesspeople or graduate students; divide them into experimental groups of roughly a dozen; give each person money and shares to trade with; and pay dividends of 24 cents at the end of each of 15 rounds, each lasting a few minutes. (Sometimes the 24 cents is a flat amount; more often there's an equal chance of getting 0, 8, 28, or 60 cents, which averages out to 24 cents.) All participants are given the same information, but they can't talk to one another and they interact only through their trading screens. Then the researchers watch what happens, repeating the same experiment with different small groups to get a larger picture.

The great thing about a laboratory experiment is that you can control the environment. Wall Street securities carry uncertainties—more, lately, than many people expected—but this experimental security is a sure thing. "The fundamental value is unambiguously defined," says the economist Charles Noussair, a professor at Tilburg University, in the Netherlands, who has run many of these experiments. "It's the expected value of the future dividend stream at any given time": 15 times 24 cents, or $3.60 at the end of the first round; 14 times 24 cents, or $3.36 at the end of the second; $3.12 at the end of the third; and so on down to zero. Participants don't even have to do the math. They can see the total expected dividends on their computer screens.

Here, finally, is a security with security—no doubt about its true value, no hidden risks, no crazy ups and downs, no bubbles and panics. The trading price should stick close to the expected value.

At least that's what economists would have thought before Vernon Smith, who won a 2002 Nobel Prize for developing experimental economics, first ran the test in the mid-1980s. But that's not what happens. Again and again, in experiment after experiment, the trading price runs up way above fundamental value. Then, as the 15th round nears, it crashes. The problem doesn't seem to be that participants are bored and fooling around. The difference between a good trading performance and a bad one is about $80 for a three-hour session, enough to motivate cash-strapped students to do their best. Besides, Noussair emphasizes, "you don't just get random noise. You get bubbles and crashes." Ninety percent of the time.

So much for security.

Read the rest here.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on December 04, 2008 • Comments

If anyone should fear a Depression, it should be journalists, who are already the equivalent of 1980s steelworkers. But instead, they seem positively giddy with anticipation at the prospect of a return to '30s-style hardship--without, of course, the real hardship of the 1930s. (We're all yuppies now.) The Boston Globe's Drake Bennett asked a bunch of people, including me, what a 21st-century Depression might look like. The results sounded pretty damned good to some people--a sure sign of an affluent society, or at least affluent commentators.

If anyone should fear a Depression, it should be journalists, who are already the equivalent of 1980s steelworkers. But instead, they seem positively giddy with anticipation at the prospect of a return to '30s-style hardship--without, of course, the real hardship of the 1930s. (We're all yuppies now.) The Boston Globe's Drake Bennett asked a bunch of people, including me, what a 21st-century Depression might look like. The results sounded pretty damned good to some people--a sure sign of an affluent society, or at least affluent commentators.

The prospect of a Depression is already creating jobs for (a few) writers. Hodding Carter IV has gotten a book deal described by Publishers Weekly this way:

After 10 years of profligate spending fueled by real estate flips, refinancing and credit card debt, the author will write about living on what he actually earns. In order to do so, he and his family of six will mine cost-saving techniques from the Great Depression and the first cookbook in America, and stay within their budget, whether that means growing their own food or bartering for things they need. Carter is writing a column based on his experiences for Gourmet.

If that last line doesn't bring a smile to your face, you really are depressed.

I applaud Carter's entrepreneurial spirit, but I don't think that living within your means really requires growing your own food or relying on ancient cookbooks. This is just a book gimmick.

Even more entrepreneurial is Blogging Queen Arianna Huffington, with a plea for more free content:

So we want to hear from you. How is the downturn affecting you and your family? Have you lost your job? Your home? Are you seeing For Sale signs on your street? Are more businesses in your town going under? How are you making ends meet? What are you hearing from your friends, your neighbors, your coworkers? Even if you still have your job and your home, and the ability to send your kids to college, how has the deep economic recession affected your outlook, your mood, your spending habits? If you work for a charity or a food bank -- what are you seeing?

Tell us your stories. Blogging about them and your feelings -- including your anger, your fears, your hopes -- is a great way to cope with the many personal, social, and professional dislocations that the hard times are producing.

Brilliant. She gets free writers. You get therapy. Readers get Depression Porn. How can Tina Brown ever compete?

Meanwhile, ReadyMade magazine, whose founders' experience with economic downturns is limited to the dot-com bust, calls on designers to imagine New Deal-style propaganda for a New Depression:

How might the current government stem the tide of economic and psychological depression? Can artists and designers help in similar ways today? It's curious that the WPA style has been reprised in the recent past as a quaint retro conceit, but today may be an opportune time for a brand-new graphic language — equal in impact to the original initiative, but decidedly different — to help rally the cause of hope and optimism.

Oh the thrill of imagining a Great Depression. It's an opportunity for Great Design and Really Cool Government.

Some designers are already profiting. The Telegraph reports that Depression-themed Christmas cards are a hit.

Some designers are already profiting. The Telegraph reports that Depression-themed Christmas cards are a hit.

So far, fortunately, these are all fantasies. Peggy Noonan is right when she observes that "everything looks the same." Stocks have crashed to 2004 levels, but today's 6.5 percent unemployment rate, while high, is a lot lower than rates in the first half of the 1980s. And don't get me started on the horrors of the 1970s. (Speaking of which, I'm eagerly awaiting the arrival of Robert Samuelson's new book, The Great Inflation and Its Aftermath: The Past and Future of American Affluence , reviewed here by Jonathan Rauch.)

, reviewed here by Jonathan Rauch.)

It's not a Depression, folks, and it wouldn't be nearly as fun to think about if it were.

UPDATE: Followup post here.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on December 04, 2008 • Comments