Design and Diabetes

Why can't the implements for dealing with a chronic disease look better? Thoughts on the need for better, more aesthetically pleasing design from a smart and sensitive blog about living with Type 1 diabetes.

Why can't the implements for dealing with a chronic disease look better? Thoughts on the need for better, more aesthetically pleasing design from a smart and sensitive blog about living with Type 1 diabetes.

In the December Atlantic, Sarah Chayes tells the fascinating, frustrating story of her Afghan adventures in entrepreneurship--and the utter lack of interest she encountered from U.S. funders charged with aiding Afghan economic development. Her business idea was brilliant--high value, low weight products that play perfectly into the U.S. aesthetic economy.

This is what we do: Eleven Afghan men and women and I scour this harried land for its (licit) bounties and turn them into beauty products. Our soaps, colored with local vegetable dyes and hand-molded and smoothed till they look like lumps of marble, and our oils, elixirs for polishing the skin, sell in boutiques that cater to the pampered in New York, Montreal, and San Francisco.

The scale of the effort--we sell about $2,500 worth of soap per month--is tiny. Still, our business, the Arghand Cooperative, represents what reports and think tanks say places like Afghanistan need: sustainable economic development. And it is almost entirely the product of private enthusiasm and generosity. From the institutional donors whose job I naively thought was to foster initiatives like ours, we have reaped much travail but almost no support.

Chayes's story is a must read. (The magazine must think so too, since this is a free link.)

Former World Bank economist William Easterly put his finger on the problem in The White Man's Burden (which I reviewed here). Aid agencies reward "planners," who work from the top down, while effective aid requires "searchers," who rely on trial and error and local knowledge. Chayes adds another dimension, suggesting that aid agencies also like to make really big grants, which tend to favor those planners. Her enterprise is probably better off without the bureaucratic entanglements that come with large-scale aid--but not if it fails for lack of capital.

One reason I support Spirit of America is that it gives U.S. military personnel deployed in Afghanistan, Iraq, and the Horn of Africa the small-scale, private funding they need to meet local needs, without a lot of bureaucracy.

Grant McCracken explains.

The LAT's My-Thuan Tran reports on one result of the policy divide I discussed in my November Atlantic column (free link). Vietnamese-Americans are leaving Orange County for Houston, which also has a large Vietnamese community, in search of housing priced for middle-class families. The story's lead:

Lan Nguyen had dreamed of owning a house since she immigrated to Southern California from Vietnam 11 years ago. But she and her husband could never scrounge up enough money for a down payment, spending most of their paychecks on rent for a cramped Garden Grove apartment.

Now, Nguyen has moved to a suburb of this Gulf Coast city, where the 28-year-old owns a new four-bedroom house with a spacious game room and access to a pool with a water slide -- all for $200,000.

Nguyen is one of many Vietnamese Americans from California who have flocked to Houston, lured by cheap real estate, a lower cost of living, bountiful business opportunities and a thriving, growing Vietnamese community.

Houston offers a slice of the American Dream to Vietnamese Americans who couldn't find it in California.

In San Jose and Orange County, home to the country's largest Vietnamese enclaves, skyrocketing rents and staggering housing prices -- even in a down market -- have become too much for some.

"At first, we thought California is the best," Nguyen said. "It's sad to move from a place we know so well. But here we own a beautiful house and are very comfortable."

Meanwhile, in housing-hostile California, I noticed a mention in passing that the Santa Monica powers-that-be had nixed the Santa Monica Mall's "an ambitious plan to replace its struggling indoor mall with an outdoor shopping venue topped with three 21-story condo towers, an apartment building and an office complex." The mall will simply remodel to integrate better with the bustling 3rd Street Promenade, and the people who might have occupied those new condos and apartments will continue to commute from parts east. (Via L.A. Curbed.)

Critics of my column thought I was too broad brush in characterizing the populations of cities like Dallas and cities like L.A. Obviously, there are still (some) middle class people in Southern California, but you don't have to be Vietnamese to feel the pull of Texas. The number of Californians moving out is larger than the number moving in, with the trend pronounced among families, and the state is losing losing native-born college grads to other states (a shortfall so far mitigated by immigrant college graduates).

Wired explains.

In chapter four of The Substance of Style, I write about "costume echoes."

Today's aesthetic imperative overturns the simplistic dichotomy between "rebellion" and "conformity," or "individual" and "mass": The result is selective conformity, an implicit or explicit drive for finer and finer gradations and the looks that identify them. Rather than choose between standing out and fitting in, we conform in some ways and diverge in others, choosing (consciously or unconsciously) a mix of meaning and pleasure, of group affiliation and individual taste. Friends develop what zoologist and author Desmond Morris calls "costume echo," adopting similar conventions of dress and carriage. Morris first identified the phenomenon when he "noticed two women walking down the street who dressed so similarly, they could have been in uniform."

Costume echoes apply to all sorts of surfaces, not just personal appearance. They can exist anywhere, including among organizations, and create new meanings through association. Consider all the late 1990s companies, particularly dot-com startups, that adopted logos with swooshes in them. "When in doubt, add one. Or two, or three," quipped a design consultant. The hopeful symbol of forward thinking even made it into the Gore-Lieberman campaign logo designed by Al Gore. Whatever its early adopters may have intended, the swoosh came to signify its era--not "the future" but "the late 1990s."

Along these lines, Justin Etheredge of CodeThinked explores the programmer dress code, part one and part two. (I had the same glasses as Dorothy Denning in the '70s. Same hairstyle, too.)

[Via Good Morning Silicon Valley.]

Beginning with Steven Levy's Newsweek cover story, Amazon's Kindle wireless ebook reader has attracted lots of speculation about the future of literature and lots of skepticism. Some critics hate it because it's not an iPod, others because it's not a book. I haven't seen the Kindle, much less used one, so I have no personal opinion. But Grant McCracken has bought one and has been blogging about it. Bottom line: He likes it very much. "It's a stunner," he says. He chose The Wealth of Nations as his first download, followed by Dan Pink's A Whole New Mind

, whose price was right. (The Substance of Style

is also available but Grant, of course, already has a hard copy.)

As the LAT's David Sarno reports, much of the resistance to the Kindle is a combination of expected weaknesses in the first edition of any new tech device--it's hard to find a specific page, for instance--with a gut reaction from people who love books.

They see the book as much more than a physical object. To many lifelong readers and writers, the book is culturally sacrosanct and even intrinsic to literature itself.

"People who care about literature care about substance and permanence," wrote novelist Jonathan Franzen, author of "The Corrections," in an e-mail. "The essence of electronics is mutability and transience. I can see travel guides and Michael Crichton novels translating into pixels easily enough. But the person who cares about Kafka wants Kafka unerasable.

"Am I fetishizing ink and paper? Sure, and I'm fetishizing truth and integrity too."

But how can truth depend on whether the words that express it are printed on an electronic page or a paper one? Are they not words in both cases? Confronted thus, Franzen remained firm.

"Yes, in theory, words are words," he replied. "But literature isn't data. The difference between Shakespeare on a BlackBerry and Shakespeare in the Arden Edition is like the difference between vows taken in a shoe store and vows taken in a cathedral."

Grant, in fact, misses the footnotes in his Kindle version of Cymbeline. But using Shakespeare as to argue that good literature must appear in printed editions is bizarre. Shakespeare presented his plays in oral form, with no footnotes and no flipping between pages. He never published his work. The folio editions came only after his death. And now they're online.

I love books too, and I wouldn't want to relinquish all those individual physical volumes for an electronic reader. But, that said, I had to give up hundreds of books when I moved back to L.A., because there just wasn't room for them all. I buy a lot fewer books than I would if I didn't have to store them (and live in fear of having them fall on my head in an earthquake). So maybe I need a Kindle after all.

I had my fourth chemo session today, which means I'm more than halfway done. (This photo was actually taken during the third session.)

As the view from my chair demonstrates, the aesthetic imperative has not yet arrived at the UCLA Oncology suite, though the attentive nurses and slightly crowded space create an odd sense of coziness. Most of the patients, including me, sleep most of the time anyway. Intravenous Benadryl is a knockout drug.

For a future column, proposed before I knew how much first-hand experience I was in for, I'd be interested in hearing from readers with thoughts about the design and aesthetics of health care environments.

Just in time for gift-giving, the Ball of Whacks now comes in blue

Just in time for gift-giving, the Ball of Whacks now comes in blue.

There's also a a multi-color version, including red, blue, and yellow pieces, but we haven't yet cracked that package. And don't forget the red original

. (For photos, see my original Ball of Whacks post here.)

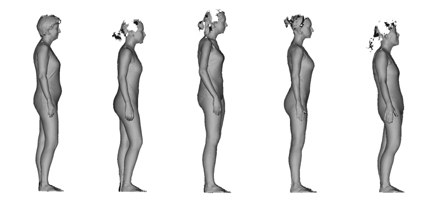

To find out, see my Atlantic column on the problem of clothing fit--now with cool body-scan video.