From Texas A&M to the CIA (or vice versa), that seems to be the question surrounding Robert Gates. Michael Barone has read Gates's memoir, From the Shadows: The Ultimate Insider's Story of Five Presidents and How They Won the Cold War , and posts an interesting report. Barone's conclusion: "The picture I get of Robert Gates from his book is that of a careful analyst, one who sees American foreign policy as generally and rightly characterized by continuity but one who sees the need for bold changes in response to rapid changes in the world--and doesn't look for answers from the government bureaucracies. He is very much aware that we have dangerous enemies in the world, and he was willing over many years to confront them and try to check their advance." (A new edition

, and posts an interesting report. Barone's conclusion: "The picture I get of Robert Gates from his book is that of a careful analyst, one who sees American foreign policy as generally and rightly characterized by continuity but one who sees the need for bold changes in response to rapid changes in the world--and doesn't look for answers from the government bureaucracies. He is very much aware that we have dangerous enemies in the world, and he was willing over many years to confront them and try to check their advance." (A new edition of the book is due in January.)

of the book is due in January.)

Posted by Virginia Postrel on November 26, 2006 • Comments

One day two samples of something called Roger von Oech's Ball of Whacks showed up in my mail. There was no press release in the package, and no explanatory letter--just two samples. Each ball contains 30 magnetic prisms--a review on the ball's Amazon page says they're rhombic triacontahedrons (I wouldn't know)--which you can reconfigure into all sorts of fun shapes, many resembly Manga spaceships or strange alien creatures. Whether playing with these stimulates productive innovation, I can't say for sure. But the Ball of Whacks does seem to illustrate the power of play, as I explored in TFAIE and related work. And it would make a great present for anyone old enough not to swallow the pieces. Here are some sample creations from Professor Postrel.

showed up in my mail. There was no press release in the package, and no explanatory letter--just two samples. Each ball contains 30 magnetic prisms--a review on the ball's Amazon page says they're rhombic triacontahedrons (I wouldn't know)--which you can reconfigure into all sorts of fun shapes, many resembly Manga spaceships or strange alien creatures. Whether playing with these stimulates productive innovation, I can't say for sure. But the Ball of Whacks does seem to illustrate the power of play, as I explored in TFAIE and related work. And it would make a great present for anyone old enough not to swallow the pieces. Here are some sample creations from Professor Postrel.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on November 26, 2006 • Comments

Last week, David Brooks used the occasion of Milton Friedman's death to lament the disappearance of important books like Capitalism and Freedom: "Then in the 1990s, those big books stopped coming. Now instead of books, we have blogs." That's nonsense, as Dan Drezner conclusively demonstrated without so much as a glance at his bookshelf. "Oh, please, spare me the crap about how today's deep thoughts fail to rival those of the past," said Dan.

Now Nick Schulz at TCS Daily has composed an even longer list than Dan's, concentrated almost entirely on big-picture economics. (Both Nick and Dan kindly include The Future and Its Enemies on their lists.) Nick's list inadvertently demonstrates what's really going on: There isn't a middle-brow consensus what books are important. As best I can tell from the NYTBR's semi-reliable archives, none of the first seven books (including mine) on Nick's list rated a review in the New York Times Book Review, and I'm not too sure about the eighth. (My search failed to turn up William Easterly's subsequent book, The White Man's Burden. which was reviewed--by me--in the NYTBR.) A book is not "big" because it addresses important ideas in a serious and significant way. A book is "big" because the right people talk about it. If there's less agreement on who the right people are--or if the right people, traditionally defined, ignore important books until they're old important books--you get laments like Brooks's.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on November 26, 2006 • Comments

On the new issue of Texas Monthly, I revisit a debate from July, looking once again at The Truth About Plano, with real reporting this time. (Access password for the issue is, yes, PLANO.)

Earlier posts: here, here, and here.

PROMOTIONAL UPDATE: If you'd like to be on my email list and receive links to new articles like this one, please enter your email address below.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on November 25, 2006 • Comments

That medical journal headline is a typo--it's supposed to read "action"--but we can hope. An excellent editorial in The Economist makes the case for organ markets. And in an article in the new American magazine edited by Jim Glassman, Sally Satel looks at some possible market structures (skip to the numbered points--unless you're a new reader, you've seen the rest before).

Although the law theoretically allows for payment of lost wages and other direct expenses, under current policy living donors almost always wind up taking a financial hit even if all goes well. Here's a story about Rick Gardner, a Wisconsin nurse who gave a kidney to a stranger, inspired by what he'd witnessed on his job.

"I was attending a seminar and a presenter talked about donating while still alive," Gardner said. "I put it in the back of mind to talk about it with my wife." Gardner who worked for an Intensive Care Unit, also spent time caring for people in a dialysis unit.

"If you ever go see people in a dialysis unit they are alive but not living," he said. "They can be going there two to three times a week at five hours a shot." Being a living donor requires sacrifice. Gardner had to take six weeks off from his job for recovery. The lost time at work cost Gardner roughly $3,000. [Emphasis added.]

Or consider Wendy Lake, a Montana woman who recently gave a kidney to her ex-husband, from whom she's been divorced for 21 years, and wasn't able to her Wal-Mart job as quickly as she expected. As reported here, her daughters and friends organized a fundraiser to help her with the bills. If you'd like to help, you can make a donation to the Wendy Lake Benefit Fund, Mountain West Bank, 12 3rd St. N.W., Great Falls, MT 59404-2869, (406) 727-2265.

Most kidney patients--and the friends and relatives from whom they're likely to get organs--are of relatively modest means. Prohibiting organ sales doesn't "help the poor." It hurts poor kidney patients, by keeping them on dialysis and shortening their lives. It hurts poor relatives of kidney patients, by forcing them to choose between saving their loved ones and taking financial and health hits. It hurts poor, healthy would-be donors by depriving them of economic opportunity. If you don't want poor people to sell their kidneys, give donors with big income tax breaks or college-loan forgiveness, so that only the affluent will get the money. Let Ivy League grads sell their kidneys instead of their eggs. But don't just prohibit compensation.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on November 21, 2006 • Comments

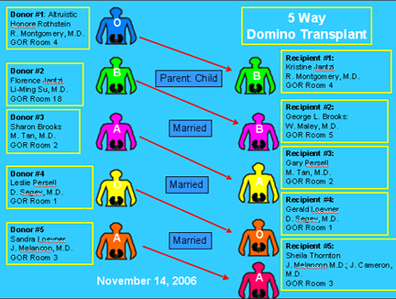

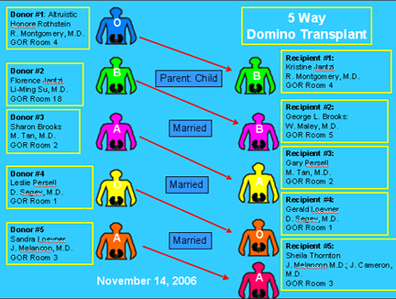

In an impressive display of surgical and organizational skill, the transplant center at Johns Hopkins has performed a "domino donor" transplant involving ten different people--five kidney donors and five recipients. Frank D. Roylance of the Baltimore Sun explains the details:

Last Tuesday's surgeries at Hopkins began when four kidney patients went to Hopkins, each with a willing, but medically incompatible parent or spouse.

It was [Honore "Honey"] Rothstein who started the dominos falling in a scheme that allowed all four patients, and a fifth who had been waiting years for a new kidney to get their new organs.

After Rothstein's first husband, Barry Castleman, died at 48 of a brain hemorrhage, all of his organs were donated. Amid their grief, Rothstein said, she and her children derived "great joy" from the notes they received from the recipients. "In a moment of desperation, you look for something good," she said.

When her daughter, Summer Castleman, 24, subsequently died of a drug overdose, none of her organs could be shared. So Rothstein offered her kidney in honor of Summer, whose framed photograph she clutched yesterday.

Her kidney went to Jantzi, whose mother, Florence Jantzi, a 65-year-old missionary from Ontario, donated a kidney to George Lonnie Brooks, 52, a semiretired mechanic from Clermont, Fla.

(When Brooks excused himself from the news conference yesterday to visit the men's room, Montgomery smiled like a proud father. "It's working," he said. "It's a beautiful thing.")

Brooks' wife, Sharon, 55, a telephone company maintenance administrator, gave a healthy kidney to Gary Persell, a 61-year-old retired film distributor from Sherman Oaks, Calif., while Persell's wife, Leslie, 61, a retired history teacher, gave her kidney to Gerald Loevner, a 77-year-old retired real estate developer from Sarasota, Fla.

Finally, Loevner's wife, Sandra, 63, a former marathon runner, gave a kidney to Sheila Thornton, also 63, a retired Baltimore City elementary school teacher from Edgewood.

Imprssive though it may be, John Heaney at Organomics finds this complex barter scheme maddening: "The story illustrates the exceptional capabilities of the American healthcare system, the ingenuity and operational expertise of the Hopkins medical staff, the selflessness of five kidney donors, and the mindless stupidity of the current transplant rules that compelled the Hopkins staff to coordinate a five-ring circus in order to save five patients' lives."

I agree, but you have to start somewhere. Crazy as it was, the 10-person swap not only saved five lives but also challenged the policy status quo. As surgeon Robert Montgomery explained at a press conference and in a further statement on the Johns Hopkins website, "Under current federal law, organs cannot be donated with the expectation that the donor will receive consideration or payment. Donors who are involved in KPD transplants make their donations with the expectation that a specific person, usually a loved one, will then receive a compatible organ from a different donor. It is feared that this expectation could be considered a form of recompense for donation, thus running afoul of the law. This provision in the current law should be clarified to encourage these important, life-saving operations on a broader scale." Even the National Kidney Foundation, sworn enemy of incentives for donors, should be able to support that reform.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on November 21, 2006 • Comments

James Bond is a glamorous icon, but we don't notice some of his original glamour today, because we've forgotten what a constrained world his early audience inhabited. Simon Winder explains in his engaging new book, The Man Who Saved Britain :

:

Casino Royale is a book all about privilege, but privilege of a very marginal and almost grimy kind, and it shows the reality of British life with startlingly greater clarity than the Coronation. The action is entirely based in and around the dull, failing Normandy coastal town of Royale--a sort of hopeless Deauville. One can imagine that French casinos circa 1950 had been through rather a lot--the previous decade having seen a "mixed crowd" at the tables. The nature of Bond's privilege is to be at Royale at all. Currency and travel restrictions meant that the Channel, the barrier essential in 1940 to keeping the Germans out, was now quite actively penning non-military British people in. The very wealthy, or those with friends in France, could make arrangements to get round the restrictions (which stayed in place in various ways until the 1970s--yet another example of how strange the recent past was), but for virtually everyone France, even blustery, sour northern France, had become as exotic as Shangri-La. Fleming could not have chosen his location more cleverly: he would need to ratchet up the flow of exotica with each of the later books (until by the end Bond is mucking around with Japanese lobster eaten live as it crawls around his table), but Britain's frame of reference had shrunk so small by the early fifties that Royale was quite enough.

The book teems with now almost invisible digs--indeed the whole idea of the casino with its theoretically limitless stakes and winnings must have seemed derangedly heady to the book's first readers. And the Anglo-American relationship has never been better summed up than when Felix Leiter hands a broke Bond an envelope crammed with lovely new dollars, allowing him to carry on playing cards with the villain, Le Chiffre. For me the heart of the book, though, must be the scene when Bond tucks into an avocado pear. An avocado! These were exotic in 1939 but they could at least be bought. Avocados only really became available again in Britain in the late 1950s and had a desirability status akin to that felt (rather more democratically) for bananas by East Germans. The sense of the exotic which Fleming had to work for really hard in later books is won here with a mere oily tropical fruit on the windswept Channel coast. Oddly, during one of the many horrible, diarrhoeic currency crises that ravaged the international value of the pound (this one in the late sixties), avocados were specifically mentioned (along with strawberries and vintage wine) as imports to be restricted under the draconian "Operation Brutus," mercifully never implemented.

The 21st-century world of the movie is still dangerous, but far less suffocating. I recommend Winder's book : to both Bond fans (some of whom will find in infuriating) and anyone interested in the mentality of postwar Britain.

: to both Bond fans (some of whom will find in infuriating) and anyone interested in the mentality of postwar Britain.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on November 21, 2006 • Comments

And .

Posted by Virginia Postrel on November 20, 2006 • Comments

"The hardest of all economic problems is what to make next. What's valuable that hasn't been done before? Businesses, and whole economies, can only grow so much by copying or incrementally improving what's already been done. For significant growth to continue, innovators have to come up with new and valuable ideas. Mere invention isn't enough; the novelty has to be something customers want." That's from my new Forbes column. It reports on recent work by economist Ned Phelps--who won the Nobel prize the week after I interviewed him--on why Europe was able to grow rapidly after World War II only to stagnate in recent decades.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on November 20, 2006 • Comments

Last week, the FDA reversed its ban on silicone gel breast implants for cosmetic surgery. Since I've written a lot on this topic over the years, lots of people wanted to know what I thought. But I was on deadline, so I didn't post anything. Fortunately Lance at A Second Hand Conjecture did, did a masterful job of tacklilng the issue, drawing from a number of my articles.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on November 20, 2006 • Comments

, and posts an interesting report. Barone's conclusion: "The picture I get of Robert Gates from his book is that of a careful analyst, one who sees American foreign policy as generally and rightly characterized by continuity but one who sees the need for bold changes in response to rapid changes in the world--and doesn't look for answers from the government bureaucracies. He is very much aware that we have dangerous enemies in the world, and he was willing over many years to confront them and try to check their advance." (A new edition

of the book is due in January.)