Growing Spare Livers

British scientists have grown a penny-sized liver from umbilical cord blood stem cells. Transplantable organs are still decades away, however, say researchers. In the short term, the mini-organs can be used for drug trials.

British scientists have grown a penny-sized liver from umbilical cord blood stem cells. Transplantable organs are still decades away, however, say researchers. In the short term, the mini-organs can be used for drug trials.

Sally Satel and I have paired articles on the kidney crisis, and our personal stories, in today's USA Today. The op-ed package also includes FAQ and interesting transplant trivia. Here's the oped page link. Scroll down for the kidney package.

UPDATE: Sally's article is in the archives here, mine is here, and the sidebar is here.

Sally and I will be on C-Span's Washington Journal Friday morning at 8:00 Eastern to discuss the articles.

A collision of meanings: The words say LDS, but the font says WSJ.

Writing on Wired.com, security expert Bruce Schneier reflects how changing threats make yesterday's architecture obsolete:

The problem is that architecture tends toward permanence, while security threats change much faster. Something that seemed a good idea when a building was designed might make little sense a century--or even a decade--later. But by then it's hard to undo those architectural decisions.

When Syracuse University built a new campus in the mid-1970s, the student protests of the late 1960s were fresh on everybody's mind. So the architects designed a college without the open greens of traditional college campuses. It's now 30 years later, but Syracuse University is stuck defending itself against an obsolete threat.

Similarly, hotel entries in Montreal were elevated above street level in the 1970s, in response to security worries about Quebecois separatists. Today the threat is gone, but those older hotels continue to be maddeningly difficult to navigate.

Security isn't the only factor that dates quickly. I recently read Alastair Gordon's lively history, Naked Airport: A Cultural History of the World's Most Revolutionary Structure. Again and again, airports have been designed to solve the problems of one era, only to confront completely different problems almost as soon as construction is complete. DFW Airport is no aesthetic treasure, for instance, but it ingeniously solved the problem of its design era: how to get people from their cars to the plane without a long walk down a corridor to the gates. Then came deregulation and hub-and-spoke systems, DFW became American's major hub, and passengers had to walk Texas-size distances to change planes. What Gordon doesn't note, and couldn't given the timing of his book, is that post-9/11, DFW is again one of the nation's more efficient airports, at least for passengers originating here. Its many entries allow security checkpoints to be spread closer to the gates, instead of routing passengers through a few chokepoints and then forcing them to travel long distances to their gates.

Megan McArdle imagines the things journalists should disclose but don't.

Randall Stross has a nice column in today's NYT on why Silicon Valley persists as the nation's startup center, despite perennial predictions that money and talent will disperse to cheaper regions. I particularly liked this point, which gets beyond the obvious explanation that venture capitalists don't like to travel:

Entrepreneurs who live in Silicon Valley also find the technical talent they need faster than they can in any other place; they pay more for that talent, but speed is the sine qua non for success. Seth J. Sternberg, the chief executive of Meebo, an instant-messaging company in Palo Alto that is backed by Sequoia, described Silicon Valley with the fervent appreciation of a recent transplant from New York, where he had suffered three separate bad experiences with start-ups, none of which had attracted venture funding.

The ecosystem in Silicon Valley, Mr. Sternberg said, includes "incredible techies, who live here because this is the epicenter, where they can find the most interesting projects to work on." The ecosystem also includes real estate agents, accountants, head hunters and lawyers who understand an entrepreneur's situation--that is, emptied bank accounts and maxed-out credit cards.

As it happens, last night Professor Postrel read me Paul Graham's excellent essay, "How to Make Wealth", whose emphasis on speed complements the Stross piece. For those who prefer their essays in bound form, I recommend Graham's Hackers and Painters, which is definitely not of interest only to geeks. My mother (a sometime painter, but mostly a literary writer) picked it up on a visit to our house and, after reading a few essays, declared that they should use it in college composition classes. She should know, since she used to teach them.

The Saudis and Israelis, who rarely agree on anything, seem to think so. According to this report, a new Saudi "law allows nonrelative donors to receive SR50,000 ($13,333) for donating an organ or part of an organ." As I reported in an earlier post, an Israeli court decision recently set the compensation due kidney donors at roughly $13,000.

In yesterday's WSJ. Thanks to all the readers who sent the link.

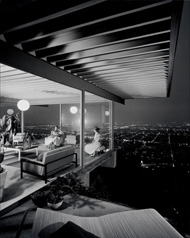

The great photographer Julius Shulman is 96 years old today. (He loves that he was born on 10/10/10.) My new Atlantic column looks at how Shulman created an appealingly human portrait of modern architecture and, by extension, how his photos and the buildings they capture reflect the ideals of the 20th century's defining metropolis--Los Angeles. (For non-Atlantic subscribers, the link is good for three days.) Here's an excerpt:

The great photographer Julius Shulman is 96 years old today. (He loves that he was born on 10/10/10.) My new Atlantic column looks at how Shulman created an appealingly human portrait of modern architecture and, by extension, how his photos and the buildings they capture reflect the ideals of the 20th century's defining metropolis--Los Angeles. (For non-Atlantic subscribers, the link is good for three days.) Here's an excerpt:

In fact, he has portrayed something more powerful: an ideal of what it's like to live in a modern house. Shulman's photographs are not simply beautiful objects in themselves or re-creations of striking buildings; they are psychologically compelling images that invite viewers to project themselves into the scene. An architectural photograph can conjure three possible desires: "I want that photograph," "I want that building," or "I want that life." Shulman's best work evokes all three. At a time when the public thought of modernism as a cold, impersonal style suited only for office buildings, he made its houses look seductively human. His photos do not merely record modern architecture, California style; they sell it. "You make people want to say, 'Gosh, I could lie down on that couch and take a nap.' Or, 'I'd love to sit at that table and have dinner there. Or entertain company around the fireplace,'" he recently told an audience at the National Building Museum, in Washington, D.C.

Shulman was discussing an eighty-three-piece retrospective of his work, "Julius Shulman, Modernity and the Metropolis." Organized by the Getty Research Institute, which in January 2004 bought his enormous archive, the exhibition opened first in Los Angeles on October 11, 2005, the day after the photographer's ninety-fifth birthday. (It is at the Art Institute of Chicago through December 3.) More than a survey of a great photographer's work, or of the architecture he documented, the exhibition is a glamorous composite portrait of the city that defined twentieth-century urban form. As modernity's metropolis, Los Angeles looks nothing like Fritz Lang's futuristic vision. Here are low-rise office buildings and backyard patios, car dealerships and gas stations, poolside chaises and sliding glass doors—a horizontal metropolis of private space. Here even Ayn Rand, whose Fountainhead celebrated skyscrapers as "the shapes of man's achievement on earth," socializes within the curving aluminum wall of her Neutra-designed patio.

Shulman is a busy man, with a steady flow of visitors at his home office, where he answers his own phone, juggles future appointments, and writes captions for a massive forthcoming volume of his photos. (For a detailed, if a little blurry, version, click on the photo.)

Martin Scorsese is supposedly making a documentary about the building of Airbus's next superjet, the A380. From the description, it sounds like a bit of a puff piece--the airplane as new cathedral. But the A380 is a much-delayed mess. The LAT's Peter Pae explains just a few of the plane's problems in today's paper. Now Airbus CEO Christian Streiff has resigned after all of three months in the job.

So here's an assignment for an enterprising LAT reporter: Whatever became of Scorsese's documentary? Between the weekend success of The Departed (two thumbs up from the Postrels) and Streiff's resignation, you won't lack for news pegs.