"Governor Signs Bill Protecting Egg Donors" is the headline on this LAT article. A more accurate title would be "Governor Signs Bill Discouraging Egg Donors" or, mirroring the actual headline's bias, "Governor Signs Bill Exploiting Egg Donors." The new law forbids paying compensation to women who provide eggs for research.

The cover story of Reason's October issue is a first-person account by an egg donor, the magazine's associate editor Kerry Howley. Her story focuses less on regulation, which is minimal for U.S. fertility treatments, and more on the contradictory rhetoric surrounding "donation"--rhetoric that, I believe, helps explain why it's so easy to ban compensation when the ban won't run afoul of noisy, well-educated, affluent would-be parents. Here's a bit of the story's conclusion:

The strongest response to such opponents is not that IVF is natural or altruistic, but that it can be neither of those things without detracting from the dignity of the child-to-be. My experiences bear no resemblance to the nightmarish scenarios thrown out by those who portray egg donation as a clumsy eugenics scheme. Strip away the nexus of fertility doctor, donor agency, and donor, and two would-be parents were hoping for a kid who would look something like them. They weren't looking for a "designer baby," so much as a close approximation of the homegrown variety.

Before we ask IVF opponents to accept the implications of new reproductive technologies, though, we might ask the same of IVF supporters. From the recipient's side, the egg donor process can be an extended effort to pretend that the donation never occurred. Straddling the natural and the artificial, egg donation embodies a contradiction. It glorifies the experience of natural pregnancy and the gift of biological children, while it in fact produces neither: Egg donor babies are the product of foreign genetic codes, and the "natural" pregnancy is manufactured in the lab. The approximation of natural pregnancy also entails a studied psychological distance from the donor who made the pregnancy possible.

Opponents of IVF have long warned that the bond between mother and child will be eroded by further advances in assisted reproduction, the implication being that mothers will eschew the time and labor of traditional pregnancies once they can outsource to the lab. In practice, IVF seems to demonstrate the opposite extreme: Women value pregnancy to such a degree that they will spend lavishly to approximate the experience, adding expense, discomfort, and ethical quandary to the already burdensome ordeal of childbirth. The desire to stick to the traditional script of family is surprisingly robust, and reproductive technologies allow potential parents to follow that script even when nature erects barriers. Though IVF entails risk, discomfort, and the prospect of having to abort multiple fetuses, many parent apparently prefer it to what might seem a far less ethically complex response to infertility: adoption. Natural motherhood is not obsolescent, as The Atlantic once predicted, but ascendant, in vogue to an almost disturbing degree.

Those who worry reproductive technologies will destroy the family probably haven't had much contact with parents who will spend many thousands of dollars to create one. If there is a risk, it is that IVF might instead ossify the definition of family, stressing insularity above openness, the appearance of a "natural" pregnancy over adoption, genetic legacy over less rigidly defined familial bonds. For all the otherworldliness of egg donation, parents who choose the process cling to the traditional: children who appear to be their own, who are born through what appears to be a natural pregnancy. It's a bold new path to very familiar territory.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on October 01, 2006 • Comments

This is Chantal Adamson, 29, who owes her new kidney--and her life--to a determined mother, a generous stranger, and MatchingDonors.com. Anne Geggis of the News Journal in Daytona Beach tells the story. Here's an excerpt:

This is Chantal Adamson, 29, who owes her new kidney--and her life--to a determined mother, a generous stranger, and MatchingDonors.com. Anne Geggis of the News Journal in Daytona Beach tells the story. Here's an excerpt:

It probably wouldn't have happened if [her mother Joan] Smith hadn't gone global with an appeal for Chantal's life. Tuesday's new beginning is the result of an innovative organ swap pioneered at one of the nation's premier hospitals.

Adamson received a kidney that was made possible because Tammy Williams 39, of McMillan, Mich., donated hers -- to an anonymous recipient. The recipient had a partner-donor at Johns Hopkins Medical Center who matched Chantal....

Tammy Williams said she would likely have gone through life without meeting Chantal or her mother--much less become a part of their family--if she hadn't typed up a press release about a Web site matching donors and people needing organs for her part-time newspaper job. It instantly piqued her curiosity.

"I've always given blood," said the cell phone saleswoman, mother of three and stepmother of six. "And this seems like the most logical step."...

"She was a mother pleading for her daughter's life," Tammy said, before Tuesday's surgery. "I couldn't imagine not helping them in that situation."

Subsequent tests showed that while Tammy wasn't a match with Chantal, she was a match with an anonymous patient on a donor-recipient list.

Brigitte Reeb, administrative director of the Johns Hopkins Medical Center, said if a program like this was set up nationally, 14,000 donors could come off the national waiting list. She said Web sites that set up Chantal and Tammy are making organ donation easier.

"Most people don't know they can do this until they find that Web site," she said.

Such four-way swaps are becoming more common. Here's a story about two men donating kidneys to each other's wives.

And, slowly but surely, public pressure is overcoming some hospitals' prejudice against finding donors on the Internet. Henry L. Davis of the Buffalo News reports on what hospital officials believe is the first transplant in New York State arranged over the Internet. When Jeanette Ostrom used MatchingDonors.com to find donor William Thomas (right) for her son Paul Cardinale (left), Buffalo General Hospital at first refused to do the transplant. But Ostrom and others persuaded the hospital to change its policy. Davis reports:

And, slowly but surely, public pressure is overcoming some hospitals' prejudice against finding donors on the Internet. Henry L. Davis of the Buffalo News reports on what hospital officials believe is the first transplant in New York State arranged over the Internet. When Jeanette Ostrom used MatchingDonors.com to find donor William Thomas (right) for her son Paul Cardinale (left), Buffalo General Hospital at first refused to do the transplant. But Ostrom and others persuaded the hospital to change its policy. Davis reports:

Only about 28,100 organ transplants are performed each year in the United States. More than 6,700 Americans die annually while waiting for an organ.

Faced with these facts and tremendous lobbying by patients, hospitals are slowly changing their policies. Buffalo General and Erie County Medical Center, the only facilities in the region that perform transplants, late last year said they would perform transplants for patients who find live donors via the Internet or other media.

Ostrom, another founder of wnykidneyconnection [a site for people in Western New York seeking donors], played a key role in persuading Kaleida Health to revise its policy.

"We came to have a tremendous appreciation for the number of people with end-stage renal disease and those waiting for a kidney," said Dr. Margaret Paroski, chief medical officer of Kaleida Health and chairwoman of the Upstate Transplant Services board of directors.

And to follow up on an earlier posting, both New Jersey pastor-donor Rick Oppelt and congregant-recipient Carol Trapp are doing well, according to this news story, despite a nurses' strike at the hospital where the transplant took place.

UPDATE: According to this followup story, Chantal Adamson is doing well.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on September 14, 2006 • Comments

Tom Vanderbilt of Design Observer reports on the charms of miniature cities: "One of the first things I like to do upon visiting a new city is to visit the scale-model version of itself. From Havana to Copenhagen, I've hunted down these miniature metropolises in dusty historical museums and under-visited exhibition halls." I never knew such things existed, let alone were common.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on September 14, 2006 • Comments

An interesting, and I think true, essay by the comic book great. It explains a lot in a short space.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on September 12, 2006 • Comments

Reader Peter Hoh writes in response to the post below:

Just read the WaPost article you linked to. Interesting. And the idea of designing procedures around human behavior makes a lot of sense.

As a former schoolteacher, I couldn't help but notice that Mr. Vedantam failed to mention how classrooms behave differently than groups of adults in an office building. For one thing, schools practice evacuations far more frequently than office buildings. Then there is the difference in the group dynamics. An office full of adults will behave differently than a room full of children and one adult whose authority they've been conditioned to respect.

As a teacher, I was never fond of fire drills, but I really disliked having to leave our building for false alarms. We teachers might like to confer with each other before we leave with our classes, but we have our responses drilled into us and our students. Our students look to us to determine how to react, and none of us teachers wants to be the last one to take our class out. But outside, we tell our nicely lined up students to stay quiet and then we gather in small groups to confer and try to make sense of the situation, just the way that office workers do before they leave the building.

The key is to make evacuation, rather than staying in, the default, so that people worry less about feeling stupid for leaving and more about being the last ones out. Drills also establish a routine that overcomes the instinct to confer. I was going to add that military discipline is all about replacing such human instincts with behavior that makes for survival in unusual circumstances. But then reader Dale Borgeson made that point better.

Granted that the civilain world is different than the military but the human tendencies are the same. What's different is the training. I was on a aircraft carrier. When General Quarters sounds (AKA Battle Stations) 5000 people have three minutes to get to where they are supposed to go. The ladders (stairs) are one person wide and quite steep. There are rules on how you move during GQ, up and forward on the starboard side and down and aft on the port. Every once in a while someone forgets what he's supposed to do and stands in a passage or at the top of a ladder trying to decide. Invariably, he gets run over and ends up on the deck. It's quite amazing how well this all works most of the time.

Everyone is trained on this sort of thing fairly intensely, both in boot camp (or OCS) and continually with drills when at sea. When the alarm sounds, not just GQ but any of the many other types of alarm, everyone moves immediately. No pauses for discussion as in your article. Everyone is trained, at least a bit, in fire fighting, how to use a hose (both as a lead and as a follower), how to use emergency breathing equipment, how to attack a fire in various situations, etc.

I remember when I went to fire fighting school in boot camp. On the first simulated GQ we had with a real fuel fire, everyone reacted as you described. When the alarm sounded ten of us assigned to the hose team ran over to the hose and just stood there. About three seconds later the instructors trained two five-inch hoses on the group. A five-inch hose at full pressure puts out a LOT of water and we were immediately on our faces in the mud (this was outdoors). The instructors were screaming at us that we were all dead and why weren't we doing what we were supposed to do. They then ran over and picked us by the back of our shirts, all the time screaming at us, "You go to the hose valve, you grab the nozzle, you pull the hose off the rack", etc. By the end of the day we were were working well together.

Perhaps becuse of this training 35 years ago, whenever I go into any public place I always look for the exits and escape paths. I wouldn't be surprised if the person that the article said just immediately left the WTC was a Navy vet.

Unfortunately, as the old Boy Who Cried Wolf story teaches, too many false alarms also constitute a kind of training. I once lived in an apartment building where the fire alarms went off constantly, always without any real fire. So after a while, no one ever left. Then one night there was a (fortunately small) fire--and the alarm didn't go off. They had to bang on our doors to get us out.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on September 12, 2006 • Comments

From a Technology Review interview with the media's favorite bioethicist, Art Caplan of Penn: "I single- handedly held up the movement toward creating markets in organs."

Posted by Virginia Postrel on September 11, 2006 • Comments

The WaPost's Shankar Vedantam has a fascinating, compact piece on the group dynamics of responding to emergencies. A sample:

Experts who study disasters are slowly coming to realize that rather than try to change human behavior to adapt to building codes and workplace rules, it may be necessary to adapt technology and rules to human behavior: In the narrow window between the siren of disaster and disaster itself, people always want to understand what is happening.

You can see this yourself the next time the fire alarm goes off at work, school or home. People will look at one another. They will ask each other: "Is it a drill? Shall we give it 30 seconds to see if it shuts off on its own? Can I just finish sending this e-mail?"

For all the disaster preparations put in place since the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the behavior of people confronted with ambiguous new information remains one of the most serious challenges for disaster planners.

"Every man for himself" is not how people respond either. As a result, they tend to survive together or die together.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on September 11, 2006 • Comments

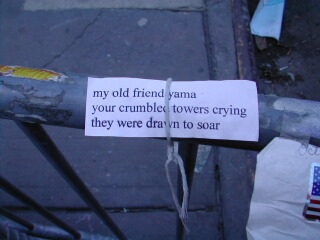

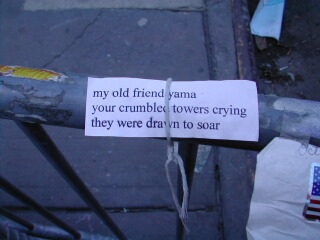

Taken in late October, when the ruins were still smoking.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on September 10, 2006 • Comments

It's certainly better to create a problem-solving business than merely to curse the anti-social acts that caused the problem in the first place. But I couldn't help thinking of Bastiat's famous essay when I read about a couple of ingenious new businesses: CutTheCrap.com, whose anti-dog-doo products include this sign (via Dallas Morning News) and MyWetStuff.com, which circumvents restrictions on carry-on baggage by shipping personal care products to your hotel room (via Dan Pink). As Bastiat pointed out, we see the glazier's profits from fixing the broken window. We don't see the more-productive uses the same time, talent, and capital could have gone to if nobody had broken the window.

It's certainly better to create a problem-solving business than merely to curse the anti-social acts that caused the problem in the first place. But I couldn't help thinking of Bastiat's famous essay when I read about a couple of ingenious new businesses: CutTheCrap.com, whose anti-dog-doo products include this sign (via Dallas Morning News) and MyWetStuff.com, which circumvents restrictions on carry-on baggage by shipping personal care products to your hotel room (via Dan Pink). As Bastiat pointed out, we see the glazier's profits from fixing the broken window. We don't see the more-productive uses the same time, talent, and capital could have gone to if nobody had broken the window.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on September 10, 2006 • Comments

So says this article's headline. Even though I knew the news already, I thought the story had something to do with Ann Taylor. (Update: Somebody fixed the headline. Screenshot here.)

Posted by Virginia Postrel on September 07, 2006 • Comments

This is Chantal Adamson, 29, who owes her new kidney--and her life--to a determined mother, a generous stranger, and

This is Chantal Adamson, 29, who owes her new kidney--and her life--to a determined mother, a generous stranger, and  And, slowly but surely, public pressure is overcoming some hospitals' prejudice against finding donors on the Internet. Henry L. Davis of the Buffalo News

And, slowly but surely, public pressure is overcoming some hospitals' prejudice against finding donors on the Internet. Henry L. Davis of the Buffalo News