Bloggers have become the favorite whipping boys of everyone who stands for Culture The Way It Was Meant to Be. In his year-end reflections the DMN's book critic Jerome Weeks lobbed such an ignorant attack that I was actually surprised: "No wonder blogospheroids still crow over the book's imminent demise — as if in revenge for ever having to read one."

Weeks is a grouchy guy--I'd be grouchy too if I had to be a book critic in Dallas--but this is the silliest attack on bloggers yet. Bloggers love books. Bloggers promote books. Bloggers write books. The InstaKing of bloggers is about to publish a book, An Army of Davids , that wouldn't even exist without blogging. Nope, blogging is Revenge of the Nerds, and nerds read books. They just may not read the same books that Jerome Weeks does.

, that wouldn't even exist without blogging. Nope, blogging is Revenge of the Nerds, and nerds read books. They just may not read the same books that Jerome Weeks does.

As you may have noticed, I haven't been blogging much lately. But I have read a bunch of interesting books, all worth sharing. Since the first of the year, I've read:

The Elusive Search for Growth by William Easterly, which combines a lucid intellectual history of the economics of growth with a sometimes heart-breaking account of how development policy has failed again and again, mostly by ignoring basic economic principles. Bono really needs to read it.

by William Easterly, which combines a lucid intellectual history of the economics of growth with a sometimes heart-breaking account of how development policy has failed again and again, mostly by ignoring basic economic principles. Bono really needs to read it.

An Anthropologist on Mars by Oliver Sacks. My next book project will likely be an exploration of heterogeneity, working title Nobody's Normal, and Sacks tells stories of people on the extremes of human difference--to the point that they sometimes seem, even to themselves, like alien intelligences (hence the title of his book). He deserves his reputation as both a great writer and a humane scientist-physician.

by Oliver Sacks. My next book project will likely be an exploration of heterogeneity, working title Nobody's Normal, and Sacks tells stories of people on the extremes of human difference--to the point that they sometimes seem, even to themselves, like alien intelligences (hence the title of his book). He deserves his reputation as both a great writer and a humane scientist-physician.

Mindsight by Colin McGinn. I picked up McGinn's newer book The Power of Movies

by Colin McGinn. I picked up McGinn's newer book The Power of Movies in December and, after reading it, realized that to understand glamour as an imaginative process, I need to delve a bit into the nature of imagination. I'm less interested than McGinn in parsing the differences between percepts and images, but I find his writing provocative and accessible. Plus he provides good bibliographies. I'm now rereading The Power of Movies

in December and, after reading it, realized that to understand glamour as an imaginative process, I need to delve a bit into the nature of imagination. I'm less interested than McGinn in parsing the differences between percepts and images, but I find his writing provocative and accessible. Plus he provides good bibliographies. I'm now rereading The Power of Movies .

.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on January 10, 2006 • Comments

I'm a fan of Bravo's Project Runway. In each episode, aspiring fashion designers complete a challenge, from concept to execution, sometimes solo and some in teams. Like Junkyard Wars, it's a rare spot on TV where you can see creative people solving problems. And, like the folks on Junkyard Wars, the designers demonstrate not just creativity under pressure but excellent manual skills. They typically have a day or two to design, buy materials for, drape and create patterns for, cut, and sew a dress. (At my best, three decades ago, I might have been able to complete the buying, cutting, and sewing parts in the time allotted.) Of course, like all good reality shows, it also has strong characters, artificially generated tension, and occasional surprises.

Project Runway exemplifies something I've noticed in covering design professions over the past few years: Design of all sorts, from the most engineering-oriented to the most "frivolous," is a redoubt of what Michael Barone calls "hard America". When Heidi Klum gathers a half dozen designers on the runway and tells them, "You represent the best and the worst," she isn't worrying about their feelings, or even their character, but about their work. Try talking like that to an English major or MBA student and watch your teaching ratings plummet.

As in life, however, the judgments aren't based only on one-dimensional notions of creativity or merit. What the client wants matters. Getting along with other designers matters (at least in some cases). Sometimes people survive a round just by being less bad, because they take fewer risks, than the competition. The process is basically fair, but the outcome doesn't always seem right--not a bad model for real life.

Here's the Amazon page for Michael Barone's book, Hard America, Soft America . The always superfantastic Manolo blogs regularly on Project Runway, with an archive here. I completely agree with his assessment of the latest challenge.

. The always superfantastic Manolo blogs regularly on Project Runway, with an archive here. I completely agree with his assessment of the latest challenge.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on January 10, 2006 • Comments

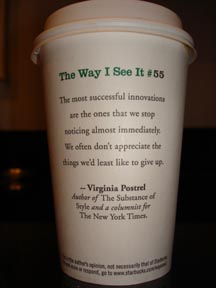

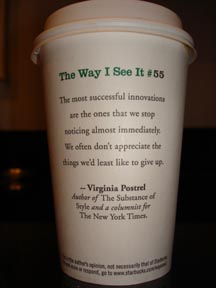

Eugene Volokh and Nick Gillespie blogged about "my" Starbucks cup back in November, but before I had a chance to see one myself, the season of the Red Cup descended on Starbucks. But the white cups are back, and I finally found one of mine. I had a little trouble, since when you actually look at a Starbucks cup it looks like this:

Starbucks went to a lot of trouble to solicit quotes from dozens of people. It designed and printed all these special cups. All the while forgetting that their cups come with a big brown cover right where the quotes go. Oops.

UPDATE: Just in case you might get the wrong idea from Dan Drezner, I didn't get paid for my Starbucks quote. Before I submitted it, however, they did send me a gift card for either $10 or $15 (I forget). I rarely drink Starbucks products--I live on Diet Coke--but it did cover some frappucinos for Professor Postrel.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on January 01, 2006 • Comments

Along with the setup, here's one of my favorite passages from Thomas Schelling's essay, "The Intimate Contest for Self-Control":

People behave sometimes as if they had two selves, one who wants clean lungs and long life and another who adores tobacco, one who yearns to improve himself by reading Adam Smith on self-command (in The Theory of Moral Sentiments) and another who would rather watch an old movie on television. The two are in continual contest for control.

As a boy I saw a movie about Admiral Byrd's Antarctic expedition and was impressed that as a boy he had gone outdoors in shirtsleeves to toughen himself against the cold. I resolved to go to bed at night with one blanket too few. That decision to go to bed minus one blanket was made by a warm boy. Another boy awoke cold in the night, too cold to retrieve the blanket, cursing the boy who had removed the blanket and resolving to restore it tomorrow. But the next bedtime it was the warm boy again, dreaming of Antarctica, who got to make the decision. And he always did it again.

Aside from its personal charms, this passage is great because it isn't clear which little boy we should root for. Is it good self-discipline or foolish fantasy to leave off the blanket?

Posted by Virginia Postrel on January 01, 2006 • Comments

Among other interesting articles, The Economist's year-end double issue includes this piece, asking how the superrich show off when luxury becomes a mass good. Is conspicuous consumptions out-of-date? I'm quoted, but the best line comes from H.L. Mencken, responding to the status-obsessed Thorstein Veblen: "Do I prefer kissing a pretty girl to kissing a charwoman because even a janitor may kiss a charwoman--or because the pretty girl looks better, smells better and kisses better?"

Posted by Virginia Postrel on January 01, 2006 • Comments

Paul Graham offers valuable thoughts on productive procrastination:

There are three variants of procrastination, depending on what you do instead of working on something: you could work on (a) nothing, (b) something less important, or (c) something more important. That last type, I'd argue, is good procrastination.

That's the "absent-minded professor," who forgets to shave, or eat, or even perhaps look where he's going while he's thinking about some interesting question. His mind is absent from the everyday world because it's hard at work in another.

That's the sense in which the most impressive people I know are all procrastinators. They're type-C procrastinators: they put off working on small stuff to work on big stuff.

What's "small stuff?" Roughly, work that has zero chance of being mentioned in your obituary. It's hard to say at the time what will turn out to be your best work (will it be your magnum opus on Sumerian temple architecture, or the detective thriller you wrote under a pseudonym?), but there's a whole class of tasks you can safely rule out: shaving, doing your laundry, cleaning the house, writing thank-you notes--anything that might be called an errand.

Good procrastination is avoiding errands to do real work.

Read the whole thing (via Marginal Revolution).

Graham's point cuts against the zeitgeist. In today's NYT, David Brooks argues that, at least for those not blessed with a Y chromosome, errands are what matters most. His paean to domesticity as the highest and best use of women's time, and maybe even men's, does not conclude with an announcement that he's quitting the Times and PBS to spend more time with driving the kids around. (For those who hate Times Select, the column is on p. 8 of Week in Review.)

Taken together, these arguments address several old questions: Why, as Sir Francis Bacon asked, is it that the most important contributors to human progress have often been childless? Why did the rise of the 18th-century city, with its coffeehouses and abundance of servants, promote science, philosophy, and literature? And, of course, why have relatively few women made enduring contributions to fields that require single-minded devotion?

Quite simply: Somebody's got to do the errands of life. You can either do them yourself, hire someone to do them, or get a wife. Historically, the last has been the most common option.

Let me be clear: I do not believe there is One Best Way to live. I do not believe that the gracious life created by attending to small chores (including, but not only, those necessary to raise children) is inferior to one devoted to more focused pursuits. What I believe, and what you'll almost never see suggested by an establishment pundit, is that different people are suited to different sorts of lives and that both strategies have their downsides and their risks. (I wrote about one aspect of this topic--the politicization of parenthood--here.)

My New Year's resolution: Fewer errands, less sleep (I sleep a lot), more reading, more writing. Still to be determined: Is blogging an errand? For me at least, I suspect so. But perhaps I can find a way to manage it.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on January 01, 2006 • Comments

I wish you all a wonderful 2006.

To help you keep those resolutions, take a look at my latest NYT column, which applies to New Year's resolutions some insights from Thomas Schelling's fascinating and important work on "self-command." I highly recommend his book Choice and Consequence . (Amazon is offering a discount for buying C&C along with Schelling's better-known The Strategy of Conflict.)

. (Amazon is offering a discount for buying C&C along with Schelling's better-known The Strategy of Conflict.)

Back in 1992, Professor Postrel and his colleague Dick Rumelt published an article arguing that the problem of self-command helps explain why people voluntarily submit themselves to organizational hierarchy (even when capital investment is not an issue) rather than simply trading in markets. The full article isn't online, but a shorter version is here.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on January 01, 2006 • Comments

At Blogs for Industry, Jim Hu does the math on dragées..

Posted by Virginia Postrel on December 21, 2005 • Comments

As expected, some readers had trouble believing the statement below that "the densest metropolis in America is Los Angeles." Guillaume Lessard's reaction was typical:

By what measure such a result be obtained? It may be possible to find a certain way to make it beat NYC, but that's because NYC ends fairly suddenly, and LA hardly does. If you look at strict city limits, then LA is 3 times as sparse as NYC. If you look at the county level, then the whole of LA County (a very large county) is only 20% more populated than NYC (a land area 12 times smaller). The metropolitan area of LA is less populated than the metropolitan area of NYC, and which area is larger? Well, LA, of course. At first blush, the only way I can see to make the above statement be true is to exclude NYC from the USA. The number mentioned in the article you cite matches the data I can find (~7600 per square mile); it's just that the number I can find for the density of NYC is ~26000 per square mile.

As a social, economic, and cultural unit, New York does not "end suddenly." To the contrary, the local area stretches well into New Jersey and Connecticut. Yes, those places are psychologically and politically different from NYC proper (and even more different from Manhattan), but Manhattan Beach and Pasadena aren't part of L.A., either. And the San Fernando Valley, while politically part of the city, has long been psychologically separate; even the mailing addresses say Tarzana or Van Nuys, not Los Angeles.

In response to my query about the numbers, Bob Bruegmann, author of Sprawl: A Compact History , wrote:

, wrote:

The only good measure of urban densities is the census bureau's "urbanized areas." These include central cities and all of the adjacent land over 1000 people per square mile (which is roughly the limit of the regularly developed suburbs and the exurbs and rural areas beyond). Using this measure the LA urbanized area had a density of over 7,000 people per square mile in 2000 making it at least the densest large urbanized area in the US. In fact, I think it is the densest urbanized area in North America (Toronto comes in at 6800 according to the Canadian census which has a similar definition of urbanized area) but I would want to do some further checking before swearing to that latter.

The problem with every other measure is that it relies on artificial political boundaries. So cities that happen to have large boundaries will appear to be very lightly populated and cities whose boundaries are tightly drawn can appear to have very high densities when, in fact, these figures have very little relationship to the actual densities at the center, at the edge or at any other given point. The same is true for "metropolitan areas" which are based on the arbitrarily drawn county lines. These are particularly useless in California where a county like San Bernardino or Riverside is counted as "urban" by the census because a little piece of it is urbanized whereas the vast majority of the county, stretching all the way to the Nevada border, is almost unpopulated desert.

There is an extremely useful compilation of statistics for urbanized areas and their densities on Wendell Cox's demographia.com.

Most of the problems people attribute to L.A.'s sprawl--notably traffic and long travel times--are actually caused by its density. The same is true in New York, however defined. Forget driving to New Jersey or Connecticut. It can take 45 minutes to travel the roughly five miles from the Upper West Side to Greenwich Village, even if you take the subway. When you pack a lot of people close together, the place tends to get crowded. That's great for culture and commerce, but it ratchets up social stress and makes getting places harder.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on December 19, 2005 • Comments

In his books , legal commentator Walter Olson has argued that litigation often creates policies that no legislature (or, in the case of employment law, union bargaining) would adopt. Writing in the LAT Sunday magazine, Andy Meisler gives an example:

, legal commentator Walter Olson has argued that litigation often creates policies that no legislature (or, in the case of employment law, union bargaining) would adopt. Writing in the LAT Sunday magazine, Andy Meisler gives an example:

Mark Pollock is a Napa-based environmental lawyer, a former Bay Area student radical and lover of fine food. Gloria Alvarez is a resident of Culver City who, for the last 33 years, has owned and operated Gloria's Cake & Candy Supplies, a tiny Westside culinary landmark jammed into a former American Legion Hall near the intersection of Sawtelle and Venice. Pollock and the seventysomething Alvarez have more than a little in common.

To be precise, on April 23, 2003, Pollock and his lone associate, Evangeline James, sued Alvarez and a who's who of names from the bakery world: "Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia Inc.; Dean & Deluca Inc.; Chefshop.com Inc.; Pfeil & Holing Inc.; Kitchen Etc.; Q.A. Products Inc.; Confectionary House; Beryl's Cake Decorating & Pastry Supplies; American Cake Supply; Albert Uster Imports Inc.; Do It With Icing; Cooking.com Inc.; Candyland Crafts Inc.; Favors by Lisa; Sugarbakers Cake, Candy and Wedding Supplies Inc.; Kitchen Conservatory Inc.; American Gourmet Foods Inc.; Annerose Hess d.b.a. Ohess; Pastry Wiz; Barry Farm Enterprises; GM Cake and Candy Supplies d.b.a. Cybercakes; Babykakes; and Does 1 through 100 inclusive."

Pollock's lawsuit swept through the close-knit world of American cake decorating like a hot knife through icing. Despite no law specifically outlawing dragées, private citizen Pollock took it upon himself to rid every last supermarket shelf, specialty food store and mail-order purveyor in California of those tiny silver-covered sugar balls you've been licking or flicking off the top of your cupcakes since you were a tyke.

Pollock is a fanatic who's determined to stamp out other people's small pleasures in pursuit of his own version of righteous living (and collect lots of money along the way). He succeeds because it costs him almost nothing to sue. His victims settle rather than spend more, in time and money, to fight his claims. Any litigation system that encourages--indeed, rewards--this petty tyranny needs serious reform.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on December 19, 2005 • Comments

, that wouldn't even exist without blogging. Nope, blogging is Revenge of the Nerds, and nerds read books. They just may not read the same books that Jerome Weeks does.

by William Easterly, which combines a lucid intellectual history of the economics of growth with a sometimes heart-breaking account of how development policy has failed again and again, mostly by ignoring basic economic principles. Bono really needs to read it.

by Oliver Sacks. My next book project will likely be an exploration of heterogeneity, working title Nobody's Normal, and Sacks tells stories of people on the extremes of human difference--to the point that they sometimes seem, even to themselves, like alien intelligences (hence the title of his book). He deserves his reputation as both a great writer and a humane scientist-physician.

by Colin McGinn. I picked up McGinn's newer book The Power of Movies

in December and, after reading it, realized that to understand glamour as an imaginative process, I need to delve a bit into the nature of imagination. I'm less interested than McGinn in parsing the differences between percepts and images, but I find his writing provocative and accessible. Plus he provides good bibliographies. I'm now rereading The Power of Movies

.