Racial Glamour

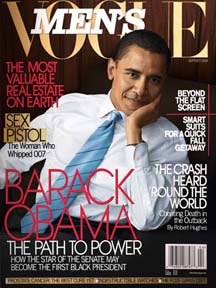

Men's Vogue has a tough editorial challenge. It's a fashion magazine for men that aims to attract a largely heterosexual audience. For its cover subjects, it needs men that other men find glamorous--that they admire for their seemingly effortless style, aspire to emulate, and do not resent. The first cover subject was George Clooney. The second was Tiger Woods. The most recent is Barack Obama.

Men's Vogue has a tough editorial challenge. It's a fashion magazine for men that aims to attract a largely heterosexual audience. For its cover subjects, it needs men that other men find glamorous--that they admire for their seemingly effortless style, aspire to emulate, and do not resent. The first cover subject was George Clooney. The second was Tiger Woods. The most recent is Barack Obama.

Obama's cover status is noteworthy. Senators are rarely style icons, and once upon a time the otherness of racial difference precluded glamour for a mass (i.e., white) American audience. "No white American, the [movie] industry maintains, would ever make his escape personality black," wrote Margaret Farrand Thorp in her 1939 book America at the Movies, one of the earliest analyses of modern glamour. As two out of three of the Men's Vogue covers illustrate, that has changed, mostly within the past decade. Nowadays, racial distance intensifies glamour by preserving the bit of mystery that true glamour requires. The distance is not so great to preclude projection, but it's great enough to prevent the intimacy (real or imagined) that would break the spell.

Writing in the New York Sun, John McWhorter considers why Obama's race is so central to his political appeal: "What gives people a jolt in their gut about the idea of President Obama is the idea that it would be a ringing symbol that racism no longer rules our land. President Obama might be, for instance, a substitute for that national apology for slavery that some consider so urgent. Surely a nation with a black president would be one no longer hung up on race." McWhorter's argument is correct as far as it goes, but it misses the apolitical glamour about Obama--and the mysterious Condoleezza Rice. That glamour depends on their race but is not solely about race, just as Jack Kennedy's glamour was not solely about wealth and Catholicism, though those characteristics made him a bit exotic to most Americans.