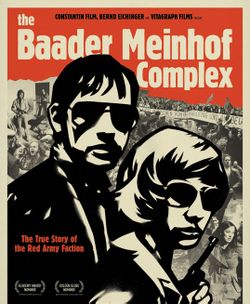

Terror & Glamour in The Baader-Meinhof Complex

Cross-posted from DeepGlamour.net

The Baader-Meinhof Complex, now playing in U.S. theaters, tells the story of the West German domestic terrorists who called themselves the Red Army Faction. Over about a decade, beginning in the late 1960s, they committed increasingly brutal acts, from bank robberies to kidnappings and murder, in the name of global revolution.

Christopher Hitchens, writing in Vanity Fair, called the movie "the year's best-made and most counter-romantic action thriller." Others have been less approving. The LAT's Kenneth Turan deemed it "an exploitation film on a socially conscious subject, the equivalent of Steven Soderbergh's 'Che' having a love child with 'The Fast and the Furious.'" When it was released in Germany last fall, some felt it was "a little too sexy for comfort" and trafficked in "terrorist-chic."

"The film portrays one murder after another without any sense of meaning, any explanation," Ulrike Meinhof's daughter Bettina Röhl, who was abandoned to a Palestinian orphanage by her terrorist mother, complained in an interview with the Associated Press. She said that "in nonverbal but very suggestive ways, the film insinuates that their motivations for terrorism are understandable."

These contradictory reactions reflect an uncomfortable fact about terrorism and political extremism: To the right audience, they can be very glamorous. They promise purity and meaning, attention and fame and a sense of belonging. Evil does not always appear ugly and unappealing. It can even be sexy.

"Terror is glamour," said Salman Rushdie in a 2006 interview with an incredulous Der Spiegel reporter. It was an astute observation. "The suicide bomber's imagination," he noted, "leads him to believe in a brilliant act of heroism, when in fact he is simply blowing himself up pointlessly and taking other people's lives." What The Baader-Meinhof Complex reminds us is that the glamour of terrorism extends not only to those who actively engage in such violent acts but to the broader public that admires or justifies those actions.

Intentionally or not, this movie about violent leftists illuminates the mass psychology of fascism. (Or maybe seeing crowds of Germans chanting and raising their fists just makes me think of Hitler.) Hitchens writes:

Consumerism is equated with Fascism so that the firebombing of department stores can be justified. Ecstatic violence and "action" become ends in themselves. One can perhaps picture Ulrike Meinhof as a "Red" resister of Nazism in the 1930s, but if the analogy to that decade is allowed, then it is very much easier to envisage her brutally handsome pal Andreas Baader as an enthusiastic member of the Brownshirts.

In its descent from glamour to ever-greater brutality and degradation, however, The Baader-Meinhof Complex most resembles a movie with no political agenda: Casino. It is no more a defense of terrorism than Casino is an ad for the Mafia.

But, of course, glamour depends on the audience and so, then, does its deconstruction. German journalist Claudia Fromme, writing in the Times of London, recounted one disconcerting reaction:

As the credits rolled and the lights went up at a screening I attended in Munich, one member of the audience raised his fist in a gesture of sympathy.

He was barely 20 years old, munching popcorn and wearing a hooded jumper. The assiduously factual debunking of the "Baader-Meinhof myth" obviously did not work for everyone in the audience.