The Iconographer

The great photographer Julius Shulman is 96 years old today. (He loves that he was born on 10/10/10.) My new Atlantic column looks at how Shulman created an appealingly human portrait of modern architecture and, by extension, how his photos and the buildings they capture reflect the ideals of the 20th century's defining metropolis--Los Angeles. (For non-Atlantic subscribers, the link is good for three days.) Here's an excerpt:

The great photographer Julius Shulman is 96 years old today. (He loves that he was born on 10/10/10.) My new Atlantic column looks at how Shulman created an appealingly human portrait of modern architecture and, by extension, how his photos and the buildings they capture reflect the ideals of the 20th century's defining metropolis--Los Angeles. (For non-Atlantic subscribers, the link is good for three days.) Here's an excerpt:

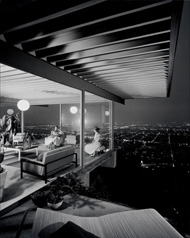

In fact, he has portrayed something more powerful: an ideal of what it's like to live in a modern house. Shulman's photographs are not simply beautiful objects in themselves or re-creations of striking buildings; they are psychologically compelling images that invite viewers to project themselves into the scene. An architectural photograph can conjure three possible desires: "I want that photograph," "I want that building," or "I want that life." Shulman's best work evokes all three. At a time when the public thought of modernism as a cold, impersonal style suited only for office buildings, he made its houses look seductively human. His photos do not merely record modern architecture, California style; they sell it. "You make people want to say, 'Gosh, I could lie down on that couch and take a nap.' Or, 'I'd love to sit at that table and have dinner there. Or entertain company around the fireplace,'" he recently told an audience at the National Building Museum, in Washington, D.C.

Shulman was discussing an eighty-three-piece retrospective of his work, "Julius Shulman, Modernity and the Metropolis." Organized by the Getty Research Institute, which in January 2004 bought his enormous archive, the exhibition opened first in Los Angeles on October 11, 2005, the day after the photographer's ninety-fifth birthday. (It is at the Art Institute of Chicago through December 3.) More than a survey of a great photographer's work, or of the architecture he documented, the exhibition is a glamorous composite portrait of the city that defined twentieth-century urban form. As modernity's metropolis, Los Angeles looks nothing like Fritz Lang's futuristic vision. Here are low-rise office buildings and backyard patios, car dealerships and gas stations, poolside chaises and sliding glass doors—a horizontal metropolis of private space. Here even Ayn Rand, whose Fountainhead celebrated skyscrapers as "the shapes of man's achievement on earth," socializes within the curving aluminum wall of her Neutra-designed patio.

Shulman is a busy man, with a steady flow of visitors at his home office, where he answers his own phone, juggles future appointments, and writes captions for a massive forthcoming volume of his photos. (For a detailed, if a little blurry, version, click on the photo.)