Why Do We Miss Flying Cars but Not Robot Maids?

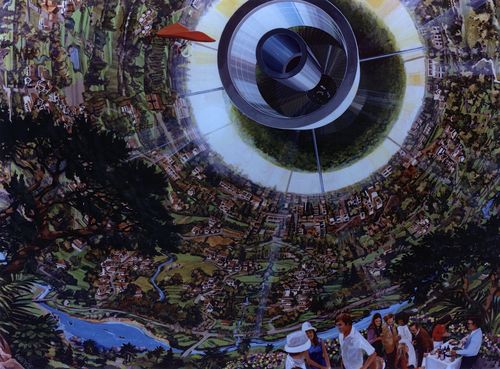

It looks like suburbia, but it still represents escape.

In my new Bloomberg View column, I criticize the trendy denigration of technological progress that doesn't solve "big problems" like going to Mars. Here's an excerpt:

In speeches, interviews and articles, [Peter] Thiel decries what he sees as the country's lack of significant innovations. "When tracked against the admittedly lofty hopes of the 1950s and 1960s, technological progress has fallen short in many domains," he wrote last year in National Review. "Consider the most literal instance of nonacceleration: We are no longer moving faster."

Such warnings serve a useful purpose. Political barriers have in fact made it harder to innovate with atoms than with bits. New technologies as diverse as hydraulic fracturing and direct-to-consumer genetic testing (neither mentioned by Thiel) attract instant and predictable opposition. As Thiel writes, "Progress is neither automatic nor mechanistic; it is rare."

But the current funk says less about economic or technological reality than it does about the power of a certain 20th-century technological glamour: all those images of space flight, elevated highways and flying cars, with their promise of escape from mundane existence into a better, more exciting place called The Future. These visions imprinted themselves so vividly on the public's consciousness that they left some of the smartest, most technologically savvy denizens of the 21st century blind to much of the progress we actually enjoy.

Read the full column here.

The column draws directly on ideas I developed in The Future and Its Enemies. But, as I was writing it, I also thought about what my forthcoming book The Power of Glamour might suggestwhy some old visions of the future are more compelling than others: Why do we miss space travel and flying cars but not robot maids (or robot dogs), "telesense," meals-in-a-pill, or all those jumpsuits? Why don't we appreciate the microwave ovens, synthetic fibers, or artificial hips?

I think it has to do with the promise of escape and transformation, which is essential to all forms of glamour. Glamour always allows the audience to imagine a different, better self in different, better circumstances.

A robot maid might improve your life but it wouldn't fundamentally change it. You'd still be yourself and the world around you would seem more-or-less the same. Except in a harried housewife, the idea of a robot maid does not excite longing. Transportation, by contrast, always implies movement and transcendence, all the more when it's fast and high. That's why space travel—like cars and trains and planes and ships and horses before it—has such potential for glamour.

I've always been fascinated by the images NASA and others used to sell the idea of space colonies in the 1970s. They always remind me of the San Fernando Valley as you come over the Sepulveda Pass from West L.A. (or, to be more accurate, the first time I saw that view it reminded me of the space colony pictures). They're selling real estate, with the same promise that every house stager uses: This could be your new, better life. ("I could be happy here.") All you have to do is move...in this case, to outer space.