After a false start on Monday--bizarre visual effects here, explanation here--Dan Drezner and I recorded a Bloggingheads.tv conversation yesterday, with topics ranging from the Oscars and Oscar fashion to privacy and the confessional practices of Dan's deadbeat students. You can view it here.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on February 28, 2007 • Comments

Reader Jim Mamer writes:

One of the side benefits of all this "spying" showed up in the news in the West Palm Beach, Florida, area last week. Kids in high and middle schools are using their cell phone cameras to photograph and put on the net pictures of students doing drugs on campus. My daughter complained about the druggies when she was at Dwyer HS about eight years ago (students shooting up heroin in the girls bathrooms...and Dwyer has a mostly white, middle and upper middle class student body), but school officials wouldn't do anything. I haven't heard much since then, but the media tend to ignore or suppress bad news about the schools.

Sounds like fodder for an episode in the Law and Order franchise.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on February 26, 2007 • Comments

The LAT's Marc Lifsher and Adrian G. Uribarri report on prospects for a ban on incandescent bulbs. It's a solid piece, but substantive objections to the idea are buried at the end.

Philips still would like to tweak the California bill so that new types of higher-efficiency incandescent halogen bulbs could be sold after 2012.

A Philips halogen bulb that uses 50% less electricity, he said, will be available this year.

Levine, the legislator, says he's open to looking at new technologies if they become commercially viable.

In the meantime, California shouldn't try to mandate compact fluorescent bulbs for every household use, said Severin Borenstein, director of the University of California Energy Institute in Berkeley.

Borenstein burns both types of bulbs at his home in the Bay Area community of Orinda but has discovered that fluorescents don't work as well as incandescent bulbs with recessed lighting fixtures, spotlights and ultra-low dimming switches.

"There are a lot of places we really should be using compact fluorescents more," he said. "But there are a lot of situations where incandescent still makes a lot of sense."

Posted by Virginia Postrel on February 25, 2007 • Comments

Amitai Etzioni, whose public persona is unmatched in its combination of self-righteousness and self-promotion, writes to the NYTBR to take issue with my review of Kieran Healy's Last Best Gifts: Altruism and the Market for Human Blood and Organs :

:

Virginia Postrel, a renowned libertarian, draws on "Last Best Gifts," by an economic sociologist, Kieran Healy (Jan. 28), to argue that the altruistic "ideology" of giving the gift of life stands in the way of developing a market in organs.

Actually, what we need is more, not fewer, evocations of our moral responsibilities....

...if the market steps in, we know from experience in other nations that the rich would purchase the organs and the poor would risk their health by selling theirs. One can be a market zealot and still argue for keeping the money-changers out of this temple.

While I appreciate being referred to as "renowned" (if only), Etzioni's letter beautifully illustrates Healy's point: that the debate over organs (and blood, which I didn't have room to discuss) unnecessarily and inaccurately posits a sharp split between market exchange and social and cultural commitments. Although Etzioni wants to box me in as a "market zealot," that's an absurdly--and deliberately--reductionist view of my thought on this issue and many others. The letter also demonstrates that Etzioni is not a particularly careful reader or at least isn't interested in the hard empirical facts of the kidney crisis. Rising to the bait, I sent him the following email:

Dear Amitai,

Thanks for calling me renowned. We can only wish...

Alas, while your proposal might help the relatively short waiting list for hearts, it wouldn't do much for the 60,000-plus Americans waiting for kidneys. The numbers simply don't add up. Only living donors can make up the difference. I've contributed a kidney. How about you?

Virginia

That last line is pretty snarky, especially since I'm well aware that Etzioni is too old to be an organ donor. But, like many other people, he treats kidney donation as an inconceivable risk to one's health and the idea of taking money for it as therefore inherently exploitative. Hence it's worth pointing out that I'm not advocating paying people for something I wasn't willing to do for free.

His response is telling, since it contradicts his anti-market propaganda in the Times.

dear viriginia

I wish my organs would be useable. I salute your donation which I am sure was made out of moral motives and not a transaction. I am not against a "market" as long as we first do as much as we can with donations, as we do with blood.

best amitai

So why, other than self-promotion, did he bother spilling ink in the Timees and defaming the idea of any incentives for organs? I suspect that the question answers itself.

On a more positive note, it looks like House will vote on Tuesday to pass the Living Organ Kidney Donation Clarification Act, which I blogged about here. The bill, sponsored by Rep. Jay Inslee and the late Rep. Charlie Norwood, will make it clear that "paired donations" are legal. Let's hope the Senate follows suit right away.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on February 25, 2007 • Comments

When the publicist for Ghost Rider offered free tickets for Dynamist readers, I asked whether there were any geographic limitations. No problem, I was told. "The tickets are valid in the United States and specific to the winner's location. There will be a specific theater for the winner to go to, corresponding to their city. The viewing will be a couple days before the release on Feb 16, 2007." That's what I repeated when I announced the contest. But it wasn't true.

Instead of movie passes, as "winner" John Tabin reported on his own blog, "FedEx...dropped off a couple of Ghost Rider hats and wallets. Yeah, I know you can hardly contain your jealousy." Sony provided no explanation either to the winners or to me. When I inquired, the publicist told me, "What happened was that it was difficult for Sony Pictures' to find a screening location in your winners' cities. Basically, their respective city did not offer any screening locations so what we did was send out Ghost Rider promotions such as shirts, caps, etc. Therefore, your winners received the products instead of the unavailable screening passes."

Both winners live in the Washington, DC, area--hardly an obscure hamlet in flyover land. The publicity firm (not to be confused with deadbeat Sony) says they'll try to send passes to the next movie they promote. That's nice of them, but not what we had in mind.

I'll give winner David Noziglia the last word: "And the gifts, if they ask, suck. Thank you for selecting me, but there should be some word out there that Sony can't be trusted. By that I mean that they lied to you."

Posted by Virginia Postrel on February 24, 2007 • Comments

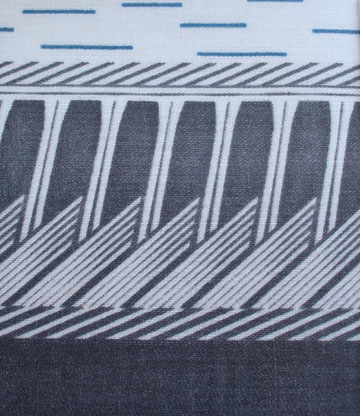

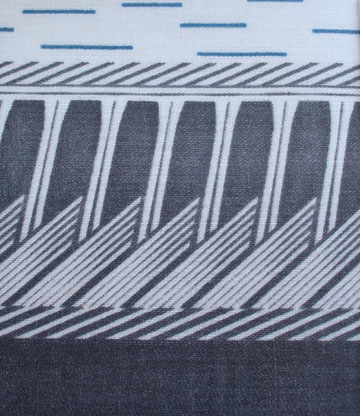

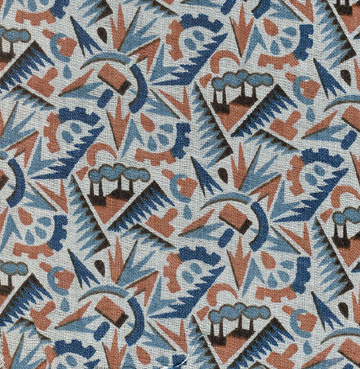

Through Sunday, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts has a small but interesting exhibit of Soviet textiles designed between 1927 and 1933. The designs were aimed at convincing a nation of peasants to embrace industrialization and, of course, the Communist revolution. Even in a centrally planned economy where the government decided what would be in the stores, the patterns proved a complete flop. "Citizens generally refused to buy or wear these propagandistic garments and household fabrics," writes Pamela Jill Kachurin in the exhibit catalog, Soviet Textiles: Designing the Modern Utopia

Through Sunday, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts has a small but interesting exhibit of Soviet textiles designed between 1927 and 1933. The designs were aimed at convincing a nation of peasants to embrace industrialization and, of course, the Communist revolution. Even in a centrally planned economy where the government decided what would be in the stores, the patterns proved a complete flop. "Citizens generally refused to buy or wear these propagandistic garments and household fabrics," writes Pamela Jill Kachurin in the exhibit catalog, Soviet Textiles: Designing the Modern Utopia . "While Soviet citizens may have tolerated the hyperbolic messages they encountered in posters, literature, and films about Soviet progress, perhaps hydroelectric dams on their pillowcases was too much to bear."

. "While Soviet citizens may have tolerated the hyperbolic messages they encountered in posters, literature, and films about Soviet progress, perhaps hydroelectric dams on their pillowcases was too much to bear."

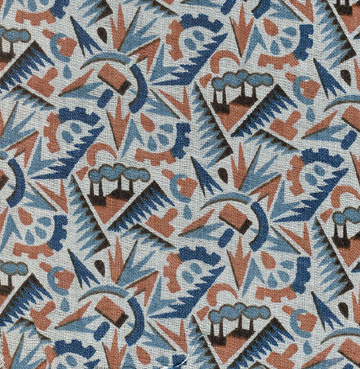

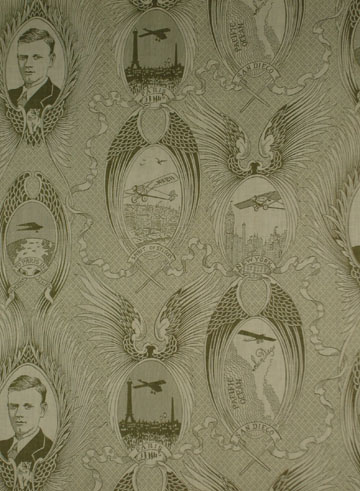

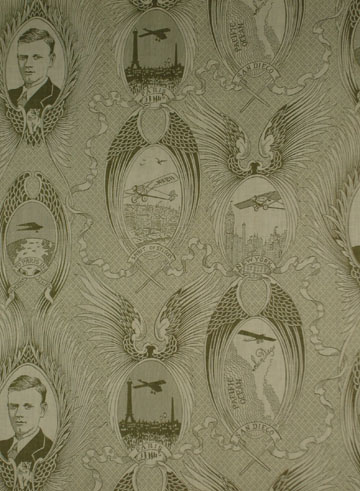

Soviet citizens did not, of course, necessarily "tolerate" the rest of that propaganda. They simply had no way to avoid it. (I shot the pillowcase design from the book, which accounts for the glare.) More likely, the propagandistic purposes undercut the graphic appeal of the designs, which are quite beautiful or at least charming, when taken out of their political context. Disconnected from central planning and totalitarian government, they might be celebratory rather than propagandistic. Hammers and sickles aside, many of them wouldn't be out of place in a mid-century American boy's bedroom. Here are a couple from the press kit, which unfortunately didn't include any of the great flight-oriented designs on display.

In the United States, similar designs were voluntarily produced and bought by willing consumers--who, of course, had plenty of traditionalist choices. These two examples are from an exhibit at the Museum at FIT, which gave me special permission to shoot photos for my glamour file. The top one features pictures of Charles Lindbergh.

For more-geometric and multicolor patterns, you'd need to look at later textile designs, which I don't have on file. Here's an example on Ebay.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on February 23, 2007 • Comments

When David Brin published The Transparent Society in 1999, surveillance was something other people did to you. Brin made the radical argument that surveillance was technologically inevitable--a notion privacy advocates found unthinkable--and that the best protection for individuals lay not in trying to limit the right to collect data on other people but in making sure that surveillance didn't become the privilege of an unwatched elite. Everyone should be able to watch everyone, including government officials; hence, the "transparent society." People hated that argument, because it accepted surveillance.

in 1999, surveillance was something other people did to you. Brin made the radical argument that surveillance was technologically inevitable--a notion privacy advocates found unthinkable--and that the best protection for individuals lay not in trying to limit the right to collect data on other people but in making sure that surveillance didn't become the privilege of an unwatched elite. Everyone should be able to watch everyone, including government officials; hence, the "transparent society." People hated that argument, because it accepted surveillance.

How 1999. Another approach is simply to ignore old ideas about privacy and make your private life public. In New York magazine, Emily Nussbaum argues that today's young people are doing exactly that and, in the process, completely redefining the idea of privacy.

[W]hat we're discussing is something more radical if only because it is more ordinary: the fact that we are in the sticky center of a vast psychological experiment, one that's only just begun to show results. More young people are putting more personal information out in public than any older person ever would--and yet they seem mysteriously healthy and normal, save for an entirely different definition of privacy. From their perspective, it's the extreme caution of the earlier generation that's the narcissistic thing. Or, as Kitty put it to me, "Why not? What's the worst that's going to happen? Twenty years down the road, someone's gonna find your picture? Just make sure it's a great picture."

And after all, there is another way to look at this shift. Younger people, one could point out, are the only ones for whom it seems to have sunk in that the idea of a truly private life is already an illusion. Every street in New York has a surveillance camera. Each time you swipe your debit card at Duane Reade or use your MetroCard, that transaction is tracked. Your employer owns your e-mails. The NSA owns your phone calls. Your life is being lived in public whether you choose to acknowledge it or not.

So it may be time to consider the possibility that young people who behave as if privacy doesn't exist are actually the sane people, not the insane ones. For someone like me, who grew up sealing my diary with a literal lock, this may be tough to accept. But under current circumstances, a defiant belief in holding things close to your chest might not be high-minded. It might be an artifact--quaint and naïve, like a determined faith that virginity keeps ladies pure. Or at least that might be true for someone who has grown up "putting themselves out there" and found that the benefits of being transparent make the risks worth it....

In essence, every young person in America has become, in the literal sense, a public figure. And so they have adopted the skills that celebrities learn in order not to go crazy: enjoying the attention instead of fighting it--and doing their own publicity before somebody does it for them.

As an old fogy, I find this behavior weird. Aside from the old-fashioned notion that some parts of life don't belong in public, I don't want to live in a small town where everyone knows everyone's business, and I wouldn't want my teenage persona following me around forever. But there is a certain kind of logic here.

The problem comes not from old-fashioned embarrassment but from adult policing. As Greg Lukianoff, the president of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, and his colleague Officer Will Creeley write in the Boston Phoenix, colleges are using their speech codes to attack students for what they post on Facebook and other online sites:

Students, be warned: the college of your choice may be watching you, and will more than likely be keeping an eye on you once you enter the hallowed campus gates. America's institutions of higher education are increasingly monitoring students' activity online and scrutinizing profiles, not only for illegal behavior, but also for what they deem to be inappropriate speech.

Contrary to popular misconceptions, the speech codes, censorship, and double standards of the culture-wars heyday of the '80s and '90s are alive and kicking, and they are now colliding with the latest explosion of communication technology. Sites like Facebook and MySpace are becoming the largest battleground yet for student free speech. Whatever campus administrators' intentions (and they are often mixed), students need to know that online jokes, photos, and comments can get them in hot water, no matter how effusively their schools claim to respect free speech. The long arm of campus officialdom is reaching far beyond the bounds of its buildings and grounds and into the shadowy realm of cyberspace.

Like Nussbaum's New York piece, this is a must-read article full of specifics. As online communication erodes the boundary between private conversation and public speech, the repressive nature of speech codes is becoming more and more apparent. (Take a look at this scary example.) They are, in fact, designed to squelch free speech--to prevent students from saying what they think, from using irony or humor in ways that might be taken as offensive, and to police not just speech but, ultimately, thought itself. (I serve on the board of FIRE, which is a great organization that deserves your support. It's watching the watchers.)

Posted by Virginia Postrel on February 23, 2007 • Comments

Brad DeLong has a wonderful post on his two-month infatuation with Keith Tribe and, by extension, Foucault and what their errors taught him about Adam Smith. I won't try to summarize. Just read it and, if possible, read Adam Smith. (Liberty Fund has put searchable versions of The Wealth of Nations and The Theory of Moral Sentiments online, but you're better off buying the real books. Nice, inexpensive, and authoritatively edited copies are available from Liberty Fund's main site. Along with the obvious classics, I also recommend Smith's Essays on Philosophical Subjects.)

Like his friend David Hume, Smith was, as Brad says, a rare genius, and he is far too little read. You don't need P.J. O'Rourke to translate. The 18th century was a great era for English prose and while the sentences are a lot longer than contemporary conventions advise, they're a lot easier to read than plenty of academic writing--whether from postmodern theorists or neoclassical economists.

to translate. The 18th century was a great era for English prose and while the sentences are a lot longer than contemporary conventions advise, they're a lot easier to read than plenty of academic writing--whether from postmodern theorists or neoclassical economists.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on February 21, 2007 • Comments

Australia will ban incandescent light bulbs by 2009. I guess the bulb-smuggling problem is easier if you're surrounded by water.

Posted by Virginia Postrel on February 19, 2007 • Comments

The LAT's David Colker tells the story of how the last soap factory in town has managed to survive despite low-cost competition from China. It's clear that soap-making doesn't have a big future in Los Angeles, but the story also a tribute to the ingenuity that has allowed the company to find new markets and new operating methods.

Hoping to trim one of his biggest remaining expenses, electricity, he contacted the Department of Water and Power. "They told me if I could shut down by 1 p.m., they could give me a much better rate," Shugar said. He moved the plant's starting time back to 5 a.m. to meet the cutoff time, resulting in 40% savings.

One of his most valuable assets was his mechanical engineer, Cheng Lim, who came to Shugar from Jergens when that company closed its Burbank plant in 1992. Lim could have stayed with the giant company, based in Cincinnati, but "my wife did not want to go," he said. "Too cold there."

Lim adapted the Shugar production line for use by fewer employees.

For example, a worker once stood at a conveyer belt to pick up the finished bars of soap, one by one, and turn them 90 degrees in preparation for the wrapping machine. Lim divided the belt into two strips, with one traveling slightly faster than the other. The bars thus turned without human intervention.

"Without him," Shugar said, "I would have to move to China."

Posted by Virginia Postrel on February 19, 2007 • Comments